Related Research Articles

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinally distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian Nestorius, who promoted specific doctrines in the fields of Christology and Mariology. The second meaning of the term is much wider, and relates to a set of later theological teachings, that were traditionally labeled as Nestorian, but differ from the teachings of Nestorius in origin, scope and terminology. The Oxford English Dictionary defines Nestorianism as "The doctrine of Nestorius, patriarch of Constantinople, by which Christ is asserted to have had distinct human and divine persons."

Justin I, also called Justin the Thracian, was Eastern Roman emperor from 518 to 527. Born to a peasant family, he rose through the ranks of the army to become commander of the imperial guard and when Emperor Anastasius died, he out-maneouvered his rivals and was elected as his successor, in spite of being around 68 years old. His reign is significant for the founding of the Justinian dynasty that included his eminent nephew, Justinian I, and three succeeding emperors. His consort was Empress Euphemia.

The Patriarch of Alexandria is the archbishop of Alexandria, Egypt. Historically, this office has included the designation "pope".

Monoenergism was a notion in early medieval Christian theology, representing the belief that Christ had only one "energy" (energeia). The teaching of one energy was propagated during the first half of the seventh century by Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople. Opposition to dyoenergism, its counterpart, would persist until Dyoenergism was espoused as Orthodoxy at the Sixth Ecumenical Council and monoenergism was rejected as heresy.

The Patriarch of Antioch is a traditional title held by the bishop of Antioch. As the traditional "overseer" of the first gentile Christian community, the position has been of prime importance in Pauline Christianity from its earliest period. This diocese is one of the few for which the names of its bishops from the apostolic beginnings have been preserved. Today five churches use the title of patriarch of Antioch: one Oriental Orthodox ; three Eastern Catholic ; and one Eastern Orthodox.

Pope Peter III of Alexandria also known as Peter Mongus was the 27th Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark.

Non-Chalcedonian Christianity comprises the branches of Christianity that do not accept theological resolutions of the Council of Chalcedon, the Fourth Ecumenical Council, held in 451. Non-Chalcedonian denominations reject the Christological Definition of Chalcedon, for varying reasons. Non-Chalcedonian Christianity thus stands in contrast to Chalcedonian Christianity.

Greek EastandLatin West are terms used to distinguish between the two parts of the Greco-Roman world and of medieval Christendom, specifically the eastern regions where Greek was the lingua franca and the western parts where Latin filled this role. Greek was spread in the context of Hellenization, whereas Latin was the official administrative language of Roman Empire, stimulating Romanization. In the east, where both languages co-existed within the Roman administration for several centuries, the use of Latin ultimately declined as the role of Greek was further encouraged by administrative changes in the empire's structure between the 3rd and 5th centuries, which led to the split between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Western Roman Empire. This Greek–Latin divide continued with the East–West Schism of the Christian world during the Early Middle Ages.

Yeghishe was an Armenian historian from the time of late antiquity, best known as the author of History of Vardan and the Armenian War, a history of a fifth-century Armenian revolt led by Vardan Mamikonian against the suppression of Christianity under Sassanid Iranian rule.

Christians in Syria make up about 10% of the population. The country's largest Christian denomination is the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch, closely followed by the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, an Eastern Catholic Churches that shares its roots with the Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch, and then by Oriental Orthodox Churches such as Syriac Orthodox Church and Armenian Apostolic Church. There are also a minority of Protestants and members of the Assyrian Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church. The city of Aleppo is believed to have the largest number of Christians in Syria. In the late Ottoman rule, a large percentage of Syrian Christians emigrated from Syria, especially after the bloody chain of events that targeted Christians in particular in 1840, the 1860 massacre, and the Assyrian genocide. According to historian Philip Hitti, approximately 900,000 Syrians arrived in the United States between 1899 and 1919. The Syrians referred include historical Syria or the Levant encompassing Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine. Syrian Christians tend to be relatively wealthy and highly educated.

Paul II the Black, also known as Paul of Bēth Ukkāme, was the Patriarch of Antioch and head of the Syriac Orthodox Church from c. 551 or 564 to his deposition in 578. He succeeded Sergius of Tella as the spiritual leader of the Syrian non-Chalcedonians, in opposition to the Chalcedonian Imperial Church, and led the nascent Syriac Orthodox Church as it endured division and persecution.

Oriental Orthodoxy is the communion of Eastern Christian Churches that recognize only three ecumenical councils—the First Council of Nicaea, the First Council of Constantinople and the Council of Ephesus. They reject the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon. Hence, these Churches are also called Old Oriental Churches or Non-Chalcedonian Churches.

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent one of its oldest branches.

In the 5th century in Christianity, there were many developments which led to further fracturing of the State church of the Roman Empire. Emperor Theodosius II called two synods in Ephesus, one in 431 and one in 449, that addressed the teachings of Patriarch of Constantinople Nestorius and similar teachings. Nestorius had taught that Christ's divine and human nature were distinct persons, and hence Mary was the mother of Christ but not the mother of God. The Council rejected Nestorius' view causing many churches, centered on the School of Edessa, to a Nestorian break with the imperial church. Persecuted within the Roman Empire, many Nestorians fled to Persia and joined the Sassanid Church thereby making it a center of Nestorianism. By the end of the 5th century, the global Christian population was estimated at 10-11 million. In 451 the Council of Chalcedon was held to clarify the issue further. The council ultimately stated that Christ's divine and human nature were separate but both part of a single entity, a viewpoint rejected by many churches who called themselves miaphysites. The resulting schism created a communion of churches, including the Armenian, Syrian, and Egyptian churches, that is today known as Oriental Orthodoxy. In spite of these schisms, however, the imperial church still came to represent the majority of Christians within the Roman Empire.

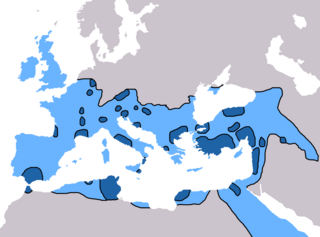

Christianity in late antiquity traces Christianity during the Christian Roman Empire — the period from the rise of Christianity under Emperor Constantine, until the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The end-date of this period varies because the transition to the sub-Roman period occurred gradually and at different times in different areas. One may generally date late ancient Christianity as lasting to the late 6th century and the re-conquests under Justinian of the Byzantine Empire, though a more traditional end-date is 476, the year in which Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus, traditionally considered the last western emperor.

Movses Khorenatsi was a prominent Armenian historian from late antiquity and the author of the History of the Armenians.

Athanasius I Gammolo was the Patriarch of Antioch and head of the Syriac Orthodox Church from 594/595 or 603 until his death in 631. He is commemorated as a saint by the Syriac Orthodox Church in the Martyrology of Rabban Sliba, and his feast day is 3 January.

The Third Council of Dvin was a church council held in 607 in the city of Dvin.

Theodosius was one of the leading Christian monks of Palestine opposed to the Council of Chalcedon (451). He was installed as bishop of Jerusalem in opposition Juvenal in 451 or 452, but was forced into exile by the emperor Marcian in 453.

Domitian was the nephew of the Roman emperor Maurice and the archbishop of Melitene in Roman Armenia from around 580 until his death. He was renowned as a diplomat and is regarded as a saint by the Chalcedonian churches for enforcing orthodoxy in the northeast of the empire. He unsuccessfully tried to convert the Persian king Khosrow II to Christianity when he helped restore him to his throne in 590–591. In the monophysite tradition, however, he is remembered for his brutal persecutions.

References

- ↑ Thomson 2010 , p. 60. Booth 2013 , p. 200, uses the title Narration on Armenian Affairs.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thomson 1991.

- 1 2 3 4 Avdoyan 2018.

- ↑ Garitte 1952 , p. 8. Ottob. gr. 77 is available online.

- ↑ Garitte 1952, p. 1.