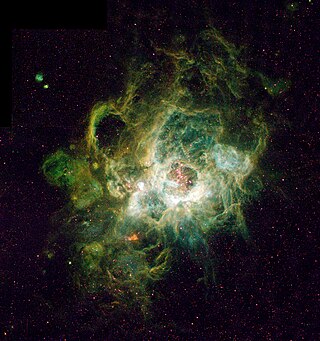

A nebula is a distinct luminescent part of interstellar medium, which can consist of ionized, neutral, or molecular hydrogen and also cosmic dust. Nebulae are often star-forming regions, such as in the Pillars of Creation in the Eagle Nebula. In these regions, the formations of gas, dust, and other materials "clump" together to form denser regions, which attract further matter and eventually become dense enough to form stars. The remaining material is then thought to form planets and other planetary system objects.

A planetary nebula is a type of emission nebula consisting of an expanding, glowing shell of ionized gas ejected from red giant stars late in their lives.

The interstellar medium (ISM) is the matter and radiation that exists in the space between the star systems in a galaxy. This matter includes gas in ionic, atomic, and molecular form, as well as dust and cosmic rays. It fills interstellar space and blends smoothly into the surrounding intergalactic space. The energy that occupies the same volume, in the form of electromagnetic radiation, is the interstellar radiation field. Although the density of atoms in the ISM is usually far below that in the best laboratory vacuums, the mean free path between collisions is short compared to typical interstellar lengths, so on these scales the ISM behaves as a gas, responding to pressure forces, and not as a collection of non-interacting particles.

The Ring Nebula is a planetary nebula in the northern constellation of Lyra.[C] Such a nebula is formed when a star, during the last stages of its evolution before becoming a white dwarf, expels a vast luminous envelope of ionized gas into the surrounding interstellar space.

An emission nebula is a nebula formed of ionized gases that emit light of various wavelengths. The most common source of ionization is high-energy ultraviolet photons emitted from a nearby hot star. Among the several different types of emission nebulae are H II regions, in which star formation is taking place and young, massive stars are the source of the ionizing photons; and planetary nebulae, in which a dying star has thrown off its outer layers, with the exposed hot core then ionizing them.

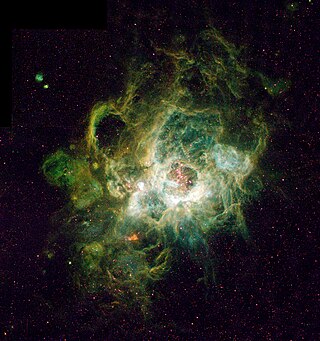

The Orion Nebula is a diffuse nebula situated in the Milky Way, being south of Orion's Belt in the constellation of Orion,[b] and is known as the middle "star" in the "sword" of Orion. It is one of the brightest nebulae and is visible to the naked eye in the night sky with an apparent magnitude of 4.0. It is 1,344 ± 20 light-years (412.1 ± 6.1 pc) away and is the closest region of massive star formation to Earth. The M42 nebula is estimated to be 25 light-years across. It has a mass of about 2,000 times that of the Sun. Older texts frequently refer to the Orion Nebula as the Great Nebula in Orion or the Great Orion Nebula.

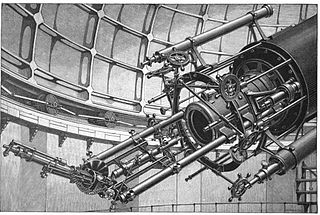

An H II region or HII region is a region of interstellar atomic hydrogen that is ionized. It is typically in a molecular cloud of partially ionized gas in which star formation has recently taken place, with a size ranging from one to hundreds of light years, and density from a few to about a million particles per cubic centimetre. The Orion Nebula, now known to be an H II region, was observed in 1610 by Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc by telescope, the first such object discovered.

Wolf–Rayet stars, often abbreviated as WR stars, are a rare heterogeneous set of stars with unusual spectra showing prominent broad emission lines of ionised helium and highly ionised nitrogen or carbon. The spectra indicate very high surface enhancement of heavy elements, depletion of hydrogen, and strong stellar winds. The surface temperatures of known Wolf–Rayet stars range from 20,000 K to around 210,000 K, hotter than almost all other kinds of stars. They were previously called W-type stars referring to their spectral classification.

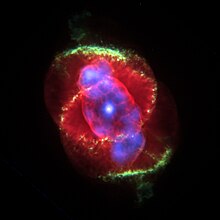

The Cat's Eye Nebula is a planetary nebula in the northern constellation of Draco, discovered by William Herschel on February 15, 1786. It was the first planetary nebula whose spectrum was investigated by the English amateur astronomer William Huggins, demonstrating that planetary nebulae were gaseous and not stellar in nature. Structurally, the object has had high-resolution images by the Hubble Space Telescope revealing knots, jets, bubbles and complex arcs, being illuminated by the central hot planetary nebula nucleus (PNN). It is a well-studied object that has been observed from radio to X-ray wavelengths. At the centre of the Cat's Eye Nebula is a dying Wolf Rayet star, the sort of which can be seen in the Webb Telescope's image of WR 124. The Cat's Eye Nebula's central star shines at magnitude +11.4. Hubble Space Telescope images show a sort of dart board pattern of concentric rings emanating outwards from the centre.

Astronomical spectroscopy is the study of astronomy using the techniques of spectroscopy to measure the spectrum of electromagnetic radiation, including visible light, ultraviolet, X-ray, infrared and radio waves that radiate from stars and other celestial objects. A stellar spectrum can reveal many properties of stars, such as their chemical composition, temperature, density, mass, distance and luminosity. Spectroscopy can show the velocity of motion towards or away from the observer by measuring the Doppler shift. Spectroscopy is also used to study the physical properties of many other types of celestial objects such as planets, nebulae, galaxies, and active galactic nuclei.

The Balmer series, or Balmer lines in atomic physics, is one of a set of six named series describing the spectral line emissions of the hydrogen atom. The Balmer series is calculated using the Balmer formula, an empirical equation discovered by Johann Balmer in 1885.

Sir William Huggins was a British astronomer best known for his pioneering work in astronomical spectroscopy together with his wife, Margaret.

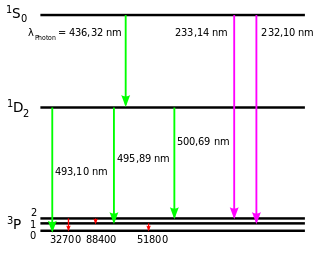

Ira Sprague Bowen was an American physicist and astronomer. In 1927 he discovered that nebulium was not really a chemical element but instead doubly ionized oxygen.

The Egg Nebula is a bipolar protoplanetary nebula approximately 3,000 light-years away from Earth. Its peculiar properties were first described in 1975 using data from the 11 μm survey obtained with sounding rocket by Air Force Geophysical Laboratory (AFGL) in 1971 to 1974.

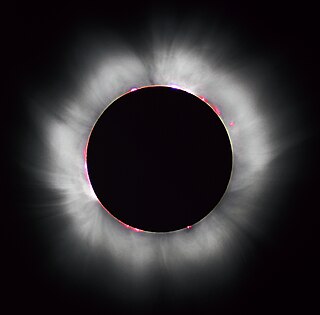

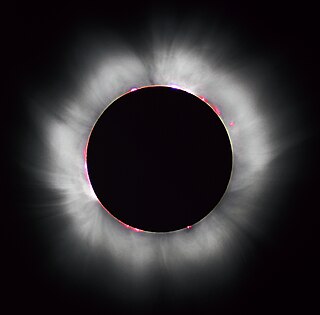

Coronium was the name of a suggested chemical element, hypothesised in the 19th century. The name, inspired by the solar corona, was given by Gruenwald in 1887. A new atomic thin green line in the solar corona was then considered to be emitted by a new element unlike anything else seen under laboratory conditions. It was later determined to be emitted by iron (Fe13+), so highly ionized that it was at that time impossible to produce in a laboratory.

Collisional excitation is a process in which the kinetic energy of a collision partner is converted into the internal energy of a reactant species.

The emission spectrum of atomic hydrogen has been divided into a number of spectral series, with wavelengths given by the Rydberg formula. These observed spectral lines are due to the electron making transitions between two energy levels in an atom. The classification of the series by the Rydberg formula was important in the development of quantum mechanics. The spectral series are important in astronomical spectroscopy for detecting the presence of hydrogen and calculating red shifts.

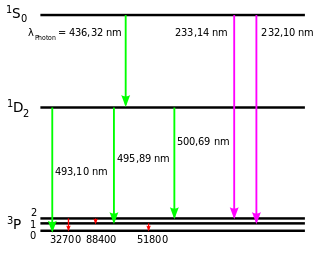

In astronomy and atomic physics, doubly ionized oxygen is the ion O2+ (O III in spectroscopic notation).

John William Nicholson, FRS was an English mathematician and physicist. Nicholson is noted as the first to create an atomic model that quantized angular momentum as h/2π. Nicholson was also the first to create a nuclear and quantum theory that explains spectral line radiation as electrons descend toward the nucleus, identifying hitherto unknown solar and nebular spectral lines. Niels Bohr quoted him in his 1913 paper of the Bohr model of the atom.

Modern spectroscopy in the Western world started in the 17th century. New designs in optics, specifically prisms, enabled systematic observations of the solar spectrum. Isaac Newton first applied the word spectrum to describe the rainbow of colors that combine to form white light. During the early 1800s, Joseph von Fraunhofer conducted experiments with dispersive spectrometers that enabled spectroscopy to become a more precise and quantitative scientific technique. Since then, spectroscopy has played and continues to play a significant role in chemistry, physics and astronomy. Fraunhofer observed and measured dark lines in the Sun's spectrum, which now bear his name although several of them were observed earlier by Wollaston.