Related Research Articles

The Proto-Indo-Europeans are a hypothetical prehistoric ethnolinguistic group of Eurasia who spoke Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family.

The Corded Ware culture comprises a broad archaeological horizon of Europe between c. 3000 BC – 2350 BC, thus from the late Neolithic, through the Copper Age, and ending in the early Bronze Age. Corded Ware culture encompassed a vast area, from the contact zone between the Yamnaya culture and the Corded Ware culture in south Central Europe, to the Rhine on the west and the Volga in the east, occupying parts of Northern Europe, Central Europe and Eastern Europe. Early autosomal genetic studies suggested that the Corded Ware culture originated from the westward migration of Yamnaya-related people from the steppe-forest zone into the territory of late Neolithic European cultures; however, paternal DNA evidence fails to support this hypothesis, and it is now proposed that the Corded Ware culture evolved in parallel with the Yamnaya, with no evidence of direct male-line descent between them.

The European Neolithic is the period when Neolithic technology was present in Europe, roughly between 7000 BC and c. 2000–1700 BC. The Neolithic overlaps the Mesolithic and Bronze Age periods in Europe as cultural changes moved from the southeast to northwest at about 1 km/year – this is called the Neolithic Expansion.

The Funnel(-neck-)beaker culture, in short TRB or TBK was an archaeological culture in north-central Europe. It developed as a technological merger of local neolithic and mesolithic techno-complexes between the lower Elbe and middle Vistula rivers. These predecessors were the (Danubian) Lengyel-influenced Stroke-ornamented ware culture (STK) groups/Late Lengyel and Baden-Boleráz in the southeast, Rössen groups in the southwest and the Ertebølle-Ellerbek groups in the north. The TRB introduced farming and husbandry as a major source of food to the pottery-using hunter-gatherers north of this line.

The Nordwestblock is a hypothetical Northwestern European cultural region that some scholars propose as a prehistoric culture in the present-day Netherlands, Belgium, far-northern France, and northwestern Germany, in an area approximately bounded by the Somme, Oise, Meuse and Elbe rivers, possibly extending to the eastern part of what is now England, during the Bronze and Iron Ages from the 3rd to the 1st millennia BCE, up to the onset of historical sources, in the 1st century BCE.

The Comb Ceramic culture or Pit-Comb Ware culture, often abbreviated as CCC or PCW, was a northeast European culture characterised by its Pit–Comb Ware. It existed from around 4200 BCE to around 2000 BCE. The bearers of the Comb Ceramic culture are thought to have still mostly followed the Mesolithic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, with traces of early agriculture.

Prehistoric Europe refers to Europe at a stage populated by humans but before the start of recorded history, beginning in the Lower Paleolithic. As history progresses, considerable regional unevenness in cultural development emerges and grows. The region of the eastern Mediterranean is, due to its geographic proximity, greatly influenced and inspired by the classical Middle Eastern civilizations, and adopts and develops the earliest systems of communal organization and writing. The Histories of Herodotus is the oldest known European text that seeks to systematically record traditions, public affairs and notable events.

The Globular Amphora culture (GAC, German: Kugelamphoren-Kultur ; c. 3400–2800 BC, is an archaeological culture in Central Europe. Marija Gimbutas assumed an Indo-European origin, though this is contradicted by newer genetic studies that show a connection to the earlier wave of Early European Farmers rather than to Western Steppe Herders from the Ukrainian and western-southern Russian steppes.

The Dnieper–Donets culture complex (DDCC) was a Mesolithic and later Neolithic culture which flourished north of the Black Sea ca. 5000-4200 BC. It has many parallels with the Samara culture, and was succeeded by the Sredny Stog culture.

The Pitted Ware culture was a hunter-gatherer culture in southern Scandinavia, mainly along the coasts of Svealand, Götaland, Åland, north-eastern Denmark and southern Norway. Despite its Mesolithic economy, it is by convention classed as Neolithic, since it falls within the period in which farming reached Scandinavia. The Pitted Ware people were largely maritime hunters, and were engaged in lively trade with both the agricultural communities of the Scandinavian interior and other hunter-gatherers of the Baltic Sea.

The Nordic Stone Age refers to the Stone Age of Scandinavia. During the Weichselian glaciation, almost all of Scandinavia was buried beneath a thick permanent ice cover, thus, the Stone Age came rather late to this region. As the climate slowly warmed up by the end of the ice age, nomadic hunters from central Europe sporadically visited the region. However, it was not until around 12,000 BCE that permanent, but nomadic, habitation in the region took root.

The Battle Axe culture, also called Boat Axe culture, is a Chalcolithic culture that flourished in the coastal areas of the south of the Scandinavian Peninsula and southwest Finland, from c. 2800 BC – c. 2300 BC. It was an offshoot of the Corded Ware culture, and replaced the Funnelbeaker culture in southern Scandinavia, probably through a process of mass migration and population replacement. It is thought to have been responsible for spreading Indo-European languages and other elements of Indo-European culture to the region. It co-existed for a time with the hunter-gatherer Pitted Ware culture, which it eventually absorbed, developing into the Nordic Bronze Age. The Nordic Bronze Age has, in turn, been considered ancestral to the Germanic peoples.

The Narva culture or eastern Baltic was a European Neolithic archaeological culture in present-day Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Kaliningrad Oblast, and adjacent portions of Poland, Belarus and Russia. A successor of the Mesolithic Kunda culture, the Narva culture continued up to the start of the Bronze Age. The culture spanned from c. 5300 to 1750 BC. The technology was that of hunter-gatherers. The culture was named after the Narva River in Estonia.

Prehistoric France is the period in the human occupation of the geographical area covered by present-day France which extended through prehistory and ended in the Iron Age with the Roman conquest, when the territory enters the domain of written history.

The Stone Age in the territory of present-day Poland is divided into the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic eras. The Paleolithic extended from about 500,000 BCE to 8000 BCE. The Paleolithic is subdivided into periods, the Lower Paleolithic, 500,000 to 350,000 BCE, the Middle Paleolithic, 350,000 to 40,000 BCE, the Upper Paleolithic, 40,000 to 10,000 BCE, and the Final Paleolithic, 10,000 to 8000 BCE. The Mesolithic lasted from 8000 to 5500 BCE, and the Neolithic from 5500 to 2300 BCE. The Neolithic is subdivided into the Neolithic proper, 5500 to 2900 BCE, and the Copper Age, 2900 to 2300 BCE.

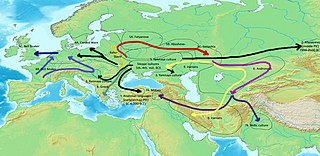

The Proto-Indo-European homeland was the prehistoric linguistic homeland of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). From this region, its speakers migrated east and west, and went on to form the proto-communities of the different branches of the Indo-European language family.

The Indo-European migrations are hypothesized migrations of Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) speakers, and subsequent migrations of people speaking derived Indo-European languages, which took place approx. 4000 to 1000 BCE, potentially explaining how these languages came to be spoken across a large area of Eurasia, spanning from the Indian subcontinent and Iranian plateau to Atlantic Europe.

The Paleo-European languages, or Old European languages, are the mostly unknown languages that were spoken in Europe prior to the spread of the Indo-European and Uralic families caused by the Bronze Age invasion from the Eurasian steppe of pastoralists whose descendant languages dominate the continent today. Today, the vast majority of European populations speak Indo-European languages, but until the Bronze Age, it was the opposite, with Paleo-European languages of non-Indo-European affiliation dominating the linguistic landscape of Europe.

Early European Farmers (EEF), First European Farmers (FEF), Neolithic European Farmers, Ancient Aegean Farmers, or Anatolian Neolithic Farmers (ANF) are names used to describe a distinct group of early Neolithic farmers who brought agriculture to Europe and Northwest Africa (Maghreb). Although the spread of agriculture from the Middle East to Europe has long been recognised through archaeology, it is only recent advances in archaeogenetics that have confirmed that this spread was strongly correlated with a migration of these farmers, and was not just a cultural exchange.

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Steppe Herders (WSH), or Western Steppe Pastoralists, is the name given to a distinct ancestral component first identified in individuals from the Chalcolithic steppe around the turn of the 5th millennium BC, subsequently detected in several genetically similar or directly related ancient populations including the Khvalynsk, Sredny Stog, and Yamnaya cultures, and found in substantial levels in contemporary European, West Asian and South Asian populations. This ancestry is often referred to as Yamnaya ancestry, Yamnaya-related ancestry, Steppe ancestry or Steppe-related ancestry.

References

- ↑ Marek Zvelebil. "Indo-European origins and the agricultural transition in Europe." In M. Kuna, N. Venclová (eds.), Whither Archeology? Papers in Honour of Evžen Neustupný. Institute of Archeology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Prague: 172–203, 1995.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Transformations in East-Central Europe from 6000 to 3000 BC: local vs. foreign patterns." Marek Nowak, Institute of Archeology, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, Documenta Praehistorica XXXIII, 2006, Neolithic Studies 13 - ↑ Bentley R.A., Chikhi L. and Price T.D. "The Neolithic transition in Europe: comparing broad scale genetic and local scale isotopic evidence". Antiquity 77 (295): 63–66, 2003

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-02-11. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Marek Zvelebil. Homo habitus: agency, structure and the transformation of tradition in the constitution of the TRB foraging farming communities in the North European Plain (ca. 4500–2000 BC), Department of Archeology, University of Sheffield, UK, Documenta Praehistorica XXXII (2005) p. 87–101. © 2005 Oddelek za arheologijo, Filozofska fakulteta – Univerza v Ljubljani, SI - ↑ Interactions between hunter-gatherers and farmers in the Early and Middle Neolithic in the Polish part of the North European Plain – Arkadiusz Marciniak. In D. Papagianni & R. Layton (eds.), Time and Change. Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives on the Long-Term in Hunter-Gatherer Societies, 115–133. Oxbow: Oxford, 2008 (approved)

- ↑ Cultural adaptive strategies in the Neolithic in central Europe within the context of palaeodemographic studies. Arkadiusz Marciniak, Journal of European Archaeology (JEA), 1, 1993/1, p. 141–151

- ↑ Frederik Kortlandt: The spread of the Indo-Europeans, 1989

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Peter Schrijver. Keltisch en de buren: 9000 jaar taalcontact; ('Celtic and the neighbours: 9000 years of language contact'), University of Utrecht, March 2007.