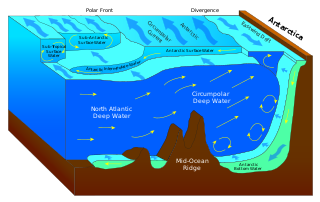

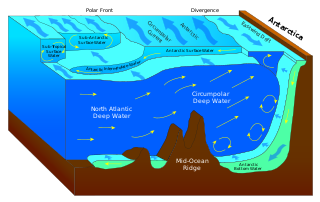

North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) is a deep water mass formed in the North Atlantic Ocean. Thermohaline circulation of the world's oceans involves the flow of warm surface waters from the southern hemisphere into the North Atlantic. Water flowing northward becomes modified through evaporation and mixing with other water masses, leading to increased salinity. When this water reaches the North Atlantic, it cools and sinks through convection, due to its decreased temperature and increased salinity resulting in increased density. NADW is the outflow of this thick deep layer, which can be detected by its high salinity, high oxygen content, nutrient minima, high 14C/12C, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

The photic zone is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological processes that supply nutrients into the upper water column. The photic zone is home to the majority of aquatic life due to the activity of the phytoplankton. The thicknesses of the photic and euphotic zones vary with the intensity of sunlight as a function of season and latitude and with the degree of water turbidity. The bottommost, or aphotic, zone is the region of perpetual darkness that lies beneath the photic zone and includes most of the ocean waters.

Downwelling is the downward movement of a fluid parcel and its properties within a larger fluid. It is closely related to upwelling, the upward movement of fluid.

The biological pump (or ocean carbon biological pump or marine biological carbon pump) is the ocean's biologically driven sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere and land runoff to the ocean interior and seafloor sediments. In other words, it is a biologically mediated process which results in the sequestering of carbon in the deep ocean away from the atmosphere and the land. The biological pump is the biological component of the "marine carbon pump" which contains both a physical and biological component. It is the part of the broader oceanic carbon cycle responsible for the cycling of organic matter formed mainly by phytoplankton during photosynthesis (soft-tissue pump), as well as the cycling of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) formed into shells by certain organisms such as plankton and mollusks (carbonate pump).

The Kuroshio Current, also known as the Black Current or Japan Current is a north-flowing, warm ocean current on the west side of the North Pacific Ocean basin. It was named for the deep blue appearance of its waters. Similar to the Gulf Stream in the North Atlantic, the Kuroshio is a powerful western boundary current that transports warm equatorial water poleward and forms the western limb of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Off the East Coast of Japan, it merges with the Oyashio Current to form the North Pacific Current.

An abyssal plain is an underwater plain on the deep ocean floor, usually found at depths between 3,000 and 6,000 metres. Lying generally between the foot of a continental rise and a mid-ocean ridge, abyssal plains cover more than 50% of the Earth's surface. They are among the flattest, smoothest, and least explored regions on Earth. Abyssal plains are key geologic elements of oceanic basins.

Bottom trawling is trawling along the seafloor. It is also referred to as "dragging". The scientific community divides bottom trawling into benthic trawling and demersal trawling. Benthic trawling is towing a net at the very bottom of the ocean and demersal trawling is towing a net just above the benthic zone. Bottom trawling can be contrasted with midwater trawling, where a net is towed higher in the water column. Midwater trawling catches pelagic fish such as anchovies and mackerel, whereas bottom trawling targets both bottom-living fish (groundfish) and semi-pelagic species such as cod, squid, shrimp, and rockfish.

The seabed is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

Bioturbation is defined as the reworking of soils and sediments by animals or plants. It includes burrowing, ingestion, and defecation of sediment grains. Bioturbating activities have a profound effect on the environment and are thought to be a primary driver of biodiversity. The formal study of bioturbation began in the 1800s by Charles Darwin experimenting in his garden. The disruption of aquatic sediments and terrestrial soils through bioturbating activities provides significant ecosystem services. These include the alteration of nutrients in aquatic sediment and overlying water, shelter to other species in the form of burrows in terrestrial and water ecosystems, and soil production on land.

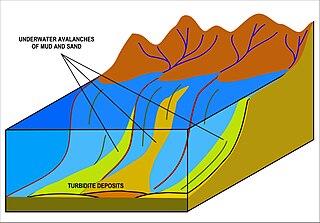

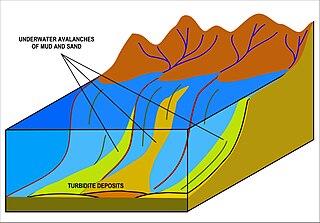

A turbidity current is most typically an underwater current of usually rapidly moving, sediment-laden water moving down a slope; although current research (2018) indicates that water-saturated sediment may be the primary actor in the process. Turbidity currents can also occur in other fluids besides water.

In oceanography and limnology, the sediment–water interface is the boundary between bed sediment and the overlying water column. The term usually refers to a thin layer of water at the very surface of sediments on the seafloor. In the ocean, estuaries, and lakes, this layer interacts with the water above it through physical flow and chemical reactions mediated by the micro-organisms, animals, and plants living at the bottom of the water body. The topography of this interface is often dynamic, as it is affected by physical processes and biological processes. Physical, biological, and chemical processes occur at the sediment-water interface as a result of a number of gradients such as chemical potential gradients, pore water gradients, and oxygen gradients.

The carbonate compensation depth (CCD) is the depth, in the oceans, at which the rate of supply of calcium carbonates matches the rate of solvation. That is, solvation 'compensates' supply. Below the CCD solvation is faster, so that carbonate particles dissolve and the carbonate shells (tests) of animals are not preserved. Carbonate particles cannot accumulate in the sediments where the sea floor is below this depth.

The Antarctic bottom water (AABW) is a type of water mass in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica with temperatures ranging from −0.8 to 2 °C (35 °F) and absolute salinities from 34.6 to 35.0 g/kg. As the densest water mass of the oceans, AABW is found to occupy the depth range below 4000 m of all ocean basins that have a connection to the Southern Ocean at that level. AABW forms the lower branch of the large-scale movement in the world's oceans through thermohaline circulation.

A dimictic lake is a body of freshwater whose difference in temperature between surface and bottom layers becomes negligible twice per year, allowing all strata of the lake's water to circulate vertically. All dimictic lakes are also considered holomictic, a category which includes all lakes which mix one or more times per year. During winter, dimictic lakes are covered by a layer of ice, creating a cold layer at the surface, a slightly warmer layer beneath the ice, and a still-warmer unfrozen bottom layer, while during summer, the same temperature-derived density differences separate the warm surface waters, from the colder bottom waters. In the spring and fall, these temperature differences briefly disappear, and the body of water overturns and circulates from top to bottom. Such lakes are common in mid-latitude regions with temperate climates.

Marine sediment, or ocean sediment, or seafloor sediment, are deposits of insoluble particles that have accumulated on the seafloor. These particles either have their origins in soil and rocks and have been transported from the land to the sea, mainly by rivers but also by dust carried by wind and by the flow of glaciers into the sea, or they are biogenic deposits from marine organisms or from chemical precipitation in seawater, as well as from underwater volcanoes and meteorite debris.

A contourite is a sedimentary deposit commonly formed on continental rises in lower slope settings, although it may occur anywhere that is below the storm wave base. Countourites are produced by thermohaline-induced deepwater bottom currents and may be influenced by wind or tidal forces. The geomorphology of contourite deposits is mainly influenced by the deepwater bottom-current velocity, sediment supply, and seafloor topography.

The benthic boundary layer (BBL) is the layer of water directly above the sediment at the bottom of a body of water. Through specific sedimentation processes, certain organisms are able to live in this deep layer of water. The BBL is generated by the friction of the water moving over the surface of the substrate, which decrease the water current significantly in this layer. The thickness of this zone is determined by many factors, including the Coriolis force. The benthic organisms and processes in this boundary layer echo the water column above them.

A river plume is a freshened water mass that is formed in the sea as a result of mixing of river discharge and saline seawater. River plumes are formed in coastal sea areas at many regions in the World. River plumes generally occupy wide-but-shallow sea surface layers bounded by sharp density gradients. The area of a river plume is 3-5 orders of magnitude greater than its depth; therefore, even small rivers with discharge rates ~1–10 m/s form river plumes with horizontal spatial extents ~10–100 m. Areas of river plumes formed by the largest rivers are ~100–1000 km2. Despite the relatively small volume of total freshwater runoff to the World Ocean, river plumes occupy up to 21% of shelf areas of the ocean, i.e., several million square kilometers.

Open ocean convection is a process in which the mesoscale ocean circulation and large, strong winds mix layers of water at different depths. Fresher water lying over the saltier or warmer over the colder leads to the stratification of water, or its separation into layers. Strong winds cause evaporation, so the ocean surface cools, weakening the stratification. As a result, the surface waters are overturned and sink while the "warmer" waters rise to the surface, starting the process of convection. This process has a crucial role in the formation of both bottom and intermediate water and in the large-scale thermohaline circulation, which largely determines global climate. It is also an important phenomena that controls the intensity of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

Water clarity is a descriptive term for how deeply visible light penetrates through water. In addition to light penetration, the term water clarity is also often used to describe underwater visibility. Water clarity is one way that humans measure water quality, along with oxygen concentration and the presence or absence of pollutants and algal blooms.