Sarekat Islam or Syarikat Islam was an Indonesian socio-political organization founded at the beginning of the 20th Century during the Dutch colonial era. Initially, SI served as a cooperative of Muslim Javanese batik traders to compete with the Chinese-Indonesian big traders. From there, SI rapidly evolved into a nationalist political organization that demanded self-governance against the Dutch colonial regime and gained wide popular support. SI was especially active during the 1910s and the early 1920s. By 1916, it claimed 80 branches with a total membership of around 350,000.

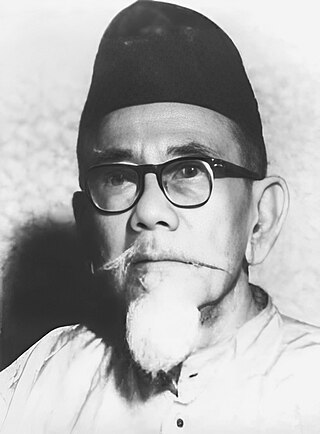

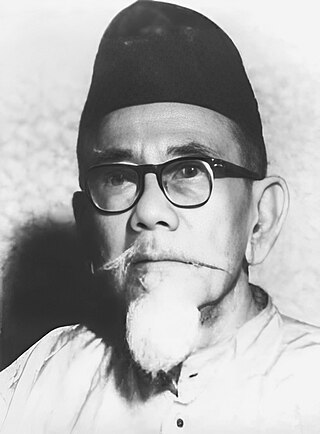

HajiAgus Salim was an Indonesian journalist, diplomat, and statesman. He served as Indonesia's Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1947 and 1949.

Ruhana Kuddus, or Rohana Kudus was the first female Indonesian journalist, founder of the newspaper Soenting Melajoe, and an activist for women's emancipation.

Djawa Tengah was a major Malay-language peranakan Chinese daily newspaper in Semarang, Dutch East Indies from 1909 to 1938. It is said to have been the first Chinese newspaper in Semarang.

Tjhoen Tjhioe was a Malay language Peranakan Chinese newspaper from Surabaya, Dutch East Indies catering mainly to the Chinese population. The full title of the paper was Tjhoen Tjhioe: Soerat kabar dagang bahasa Melajoe jang moeat roepa kabar penting bagi bangsa Tionghoa. Although the paper only existed for a short time, during that time it was recognized as one of the top Chinese newspapers in the Indies, alongside Sin Po and Perniagaan.

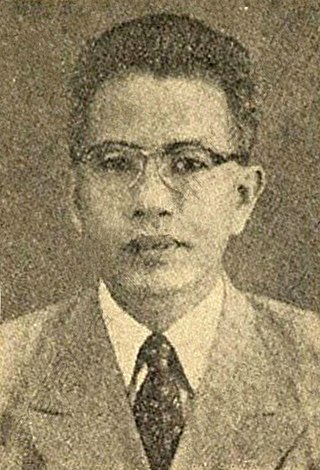

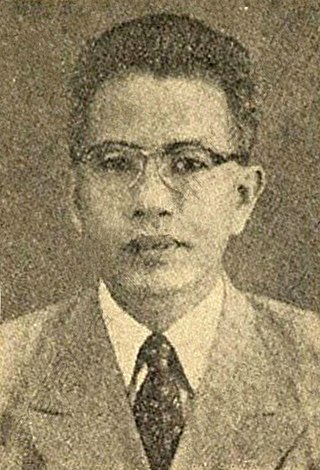

Mohammad Tabrani Soerjowitjitro was an Indonesian journalist and politician. He originated from the island of Madura and received journalistic education in Europe. In his early journalistic career, Tabrani was a major proponent of the Indonesian language as a national language. Later on, he became the editor of the Pemandangan newspaper and promoted the independence of Indonesia through parliamentary means.

Djawi-Hisworo was a newspaper printed in Surakarta, Dutch East Indies from 1909 to 1919 in Malay and Javanese. It was considered the mouthpiece of the early Javanese self-improvement organization Boedi Oetomo.

Parada Harahap was an important journalist and writer from the late colonial period and early independence era in Indonesia. In the 1930s, he was called the "king of the Java press". He pioneered a new kind of politically neutral Malay language newspaper in the 1930s which would cater to the rising middle class of the Indies.

Raden Darsono Notosudirdjo, more commonly known simply as Darsono, was a journalist and editor of Sinar Hindia, an activist in the Sarekat Islam and chairman of the Indonesian Communist Party from 1920 to 1925.

Adolf Baars was a Dutch-Jewish Communist, engineer, and writer who is largely remembered today for his early role in the Indische Sociaal-Democratische Vereeniging and the Indonesian Communist Party.

Warna Warta was a Malay language Peranakan Chinese newspaper published in Semarang, Dutch East Indies from 1902 to 1933. Alongside its more popular rival Djawa Tengah, it was highly influential among the Chinese Indonesian population of Semarang during this time.

Fatimah Hasan Delais (1915-1953), also known by the pen name Hamidah, was an Indonesian novelist and poet. Her novel Kehilangan mestika, 1935, was among the first by a female author to be published by Balai Pustaka; she was one of only a handful of Indonesian women authors to be published at all in the Dutch East Indies, alongside Saadah Alim, Sariamin Ismail, Soewarsih Djojopoespito and a few others.

Kwee Kek Beng was a Chinese Indonesian journalist and writer, best known for being editor-in-chief of the popular Malay language newspaper Sin Po from 1925 to 1947.

Raden Pandji Wirasmo Notonindito, often referred to as Dr. Notonindito, was a Javanese accountant, intellectual and politician in the Dutch East Indies. He founded the short-lived Indonesian Fascist Party in 1933.

The Indonesian Fascist Party was a short-lived Fascist political party founded in Bandung, Dutch East Indies in the summer of 1933 by a Javanese economist and politician named Notonindito. Although it did not last long and is poorly documented, it is often cited as an example of how European Fascist ideas could manifest themselves in an Asian context, as well as appearing in conspiracy literature exaggerating its importance.

Soenting Melajoe was a Malay language newspaper published in Padang, Sumatra's Westkust Regency, Dutch East Indies from 1912 to 1921. Its full title was Soenting Melajoe: soerat chabar perempoean di Alam Minang Kabau. It was edited by Ruhana Kuddus, an early women's education activist, and was the first newspaper for women published in West Sumatra.

Aliarcham (c.1901-1933) was a Sarekat Islam and Indonesian Communist Party party leader, activist and theoretician in the Dutch East Indies. He was a major figure behind the PKI's turn to more radical policies in the mid-1920s. He was arrested by Dutch authorities in 1925 and exiled to the Boven-Digoel concentration camp, where he died in 1933. He became a well-known Martyr, especially among Communists and Indonesian nationalists.

Soetitah was a Sarekat Islam and Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) propagandist, activist, and schoolteacher in Semarang, Dutch East Indies in the 1910s and 1920s. She was a close ally of Semaun, Tan Malaka, and other Semarang communists of the time and was chair of the women's section of the party in the early 1920s. She was exiled by the Dutch to the Boven-Digoel concentration camp from 1927 to 1930.

Moenasiah was a Sarekat Islam and Indonesian Communist Party leader active in Semarang, Central Java, Dutch East Indies during the 1920s. She was chairperson of the women's section of the Communist Party for a time in the 1920s. She was exiled by Dutch authorities to Boven-Digoel concentration camp from 1927 to 1930.

Abdoe'lxarim M. S., who was born Abdoel Karim bin Moehamad Soetan, was a journalist and Communist Party of Indonesia leader. He was interned in Boven-Digoel concentration camp from 1927 to 1932. During World War II, he collaborated with the Japanese and became an important figure in recruiting support for them in Sumatra; after their defeat he then became a key figure in the anti-Dutch republican forces during the Indonesian National Revolution.