Related Research Articles

The British National Formulary (BNF) is a United Kingdom (UK) pharmaceutical reference book that contains a wide spectrum of information and advice on prescribing and pharmacology, along with specific facts and details about many medicines available on the UK National Health Service (NHS). Information within the BNF includes indication(s), contraindications, side effects, doses, legal classification, names and prices of available proprietary and generic formulations, and any other notable points. Though it is a national formulary, it nevertheless also includes entries for some medicines which are not available under the NHS, and must be prescribed and/or purchased privately. A symbol clearly denotes such drugs in their entry.

Medical ethics is an applied branch of ethics which analyzes the practice of clinical medicine and related scientific research. Medical ethics is based on a set of values that professionals can refer to in the case of any confusion or conflict. These values include the respect for autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice. Such tenets may allow doctors, care providers, and families to create a treatment plan and work towards the same common goal. It is important to note that these four values are not ranked in order of importance or relevance and that they all encompass values pertaining to medical ethics. However, a conflict may arise leading to the need for hierarchy in an ethical system, such that some moral elements overrule others with the purpose of applying the best moral judgement to a difficult medical situation. Medical ethics is particularly relevant in decisions regarding involuntary treatment and involuntary commitment.

A prescription, often abbreviated ℞ or Rx, is a formal communication from a physician or other registered health-care professional to a pharmacist, authorizing them to dispense a specific prescription drug for a specific patient. Historically, it was a physician's instruction to an apothecary listing the materials to be compounded into a treatment—the symbol ℞ comes from the first word of a medieval prescription, Latin: Recipere, that gave the list of the materials to be compounded.

A prescription drug is a pharmaceutical drug that legally requires a medical prescription to be dispensed. In contrast, over-the-counter drugs can be obtained without a prescription. The reason for this difference in substance control is the potential scope of misuse, from drug abuse to practicing medicine without a license and without sufficient education. Different jurisdictions have different definitions of what constitutes a prescription drug.

The pharmaceutical industry discovers, develops, produces, and markets drugs or pharmaceutical drugs for use as medications to be administered to patients, with the aim to cure them, vaccinate them, or alleviate symptoms. Pharmaceutical companies may deal in generic or brand medications and medical devices. They are subject to a variety of laws and regulations that govern the patenting, testing, safety, efficacy using drug testing and marketing of drugs. The global pharmaceuticals market produced treatments worth $1,228.45 billion in 2020 and showed a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 1.8%.

Many countries have measures in place to limit advertising by pharmaceutical companies.

Alosetron, sold under the brand name Lotronex among others, is a 5-HT3 antagonist used for the management of severe diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in women only.

Medicalization is the process by which human conditions and problems come to be defined and treated as medical conditions, and thus become the subject of medical study, diagnosis, prevention, or treatment. Medicalization can be driven by new evidence or hypotheses about conditions; by changing social attitudes or economic considerations; or by the development of new medications or treatments.

Clinical trials publication is having research published in a peer reviewed journal following clinical trials. Most investigators will want to have such a publication but the nature of clinical trials may create special considerations and obstacles.

Pharmaceutical sales representatives are salespeople employed by pharmaceutical companies to persuade doctors to prescribe their drugs to patients. Drug companies in the United States spend ~$5 billion annually sending representatives to doctors, to provide product information, answer questions on product use, and deliver product samples. These interactions are governed according to limits established by the Code on Interactions with Health Care Professionals, created by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). This code came into practice in 2002 and has since been updated to help define ethical interactions between health care professionals and the pharmaceutical companies

The American Medical Student Association (AMSA), founded in 1950 and based in Washington, D.C., is an independent association of physicians-in-training in the United States. AMSA is a student-governed national organization.They have a membership of 68,000 medical students, premedical students, interns, medical residents, and practicing physicians from across the country.

Disease mongering is a pejorative term for the practice of widening the diagnostic boundaries of illnesses and aggressively promoting their public awareness in order to expand the markets for treatment.

Direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) refers to the marketing and advertising of pharmaceutical products directly to consumers as patients, as opposed to specifically targeting health professionals. The term is synonymous primarily with the advertising of prescription medicines via mass media platforms—most commonly on television and in magazines, but also via online platforms.

The ethics involved within pharmaceutical sales is built from the organizational ethics, which is a matter of system compliance, accountability and culture. Organizational ethics are used when developing the marketing and sales strategy to both the public and the healthcare profession of the strategy. Organizational ethics are best demonstrated through acts of fairness, compassion, integrity, honor, and responsibility.

David Franklin is an American microbiologist and former fellow of Harvard Medical School who while employed by Parke-Davis filed the 1996 whistleblower lawsuit exposing their illegal promotion of Neurontin (gabapentin) for off-label uses. Franklin's suit, filed on behalf of the citizens of the United States under the qui tam provisions of US federal and state law, uncovered illegal pharmaceutical industry practices and created new legal precedent that resulted in a cascade of criminal convictions and civil and criminal penalties against Pfizer and several other pharmaceutical companies totalling more than $7 billion. Civil cases also followed Franklin v. Parke-Davis. Insurance companies, led by Kaiser Permanente, sued Pfizer for fraud and violation of the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act; the Kaiser case settled in April 2014 after Pfizer's appeal at the US Supreme Court was rejected. Franklin v. Pfizer also spawned more than a thousand wrongful death (suicide) suits associated with use of Neurontin. Numerous books have addressed the social, economic and healthcare implications of Dr. Franklin's stance and actions. The settlement was the first off-label promotion settlement under the False Claims Act.

PharmedOut (PhO) is a Georgetown University Medical Center project founded in 2006. It is directed by Adriane Fugh-Berman. The stated mission of the organization is to advance evidence-based prescribing and educate healthcare professionals about pharmaceutical marketing practices. Stated goals are to: 1. Document and disseminate information about how pharmaceutical companies influence prescribing 2. Foster access to unbiased information about drugs and 3. Encourage physicians to choose pharma-free CME.

Sorrell v. IMS Health Inc., 564 U.S. 552 (2011), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that a Vermont statute that restricted the sale, disclosure, and use of records that revealed the prescribing practices of individual doctors violated the First Amendment.

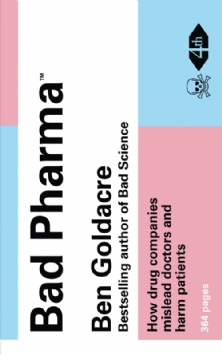

Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients is a book by the British physician and academic Ben Goldacre about the pharmaceutical industry, its relationship with the medical profession, and the extent to which it controls academic research into its own products. It was published in the UK in September 2012 by the Fourth Estate imprint of HarperCollins, and in the United States in February 2013 by Faber and Faber.

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act is a 2010 United States healthcare law to increase transparency of financial relationships between health care providers and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

The medical–industrial complex is a network of interactions between pharmaceutical corporations, health care personnel, and medical conglomerates to supply health care-related products and services for a profit. The term is a product of the Military–industrial complex and builds from the basis of that concept.

References

- ↑ Tayal U (2004-05-15), No free lunch [ permanent dead link ]. BMJ Careers. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- 1 2 3 O'Reilly KB (2006-01-16), Buy your own lunch: No chance of reciprocity: One doctor's crusade against gifts from the drug industry has grown into a small, but vocal, group. American Medical News. American Medical Association. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- 1 2 Ewing A (2005-04-18), ACP and No Free Lunch: Setting the Record Straight Archived 2007-06-07 at the Wayback Machine . American College of Physicians. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- 1 2 Lenzer J (2005-09-24), Doctors refuse exhibit space to group campaigning against drug company influence. BMJ: British Medical Journal. Volume 331, Issue 7518, Page 653. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- ↑ Edwards J (2005-09-16), “No Free Lunch” gets no free ride. Brandweek. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- ↑ Edwards J (2005-10-21), Let's eat: ‘No Free Lunch’ gets a place at the table. Brandweek. Retrieved on 2007-10-07.

- ↑ Becker K (2004-12-08), Medical students declare 'pharmfree day' to combat biased industry temptations. Medical News Today. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- ↑ The No Free Lunch pledge Archived 2009-02-07 at the Wayback Machine . No Free Lunch website. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Victory J (2004-05-04), Fighting freebies. The Journal News. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- ↑ Koerner BI (March/April, 2003), Dr. No Free Lunch. Mother Jones, Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- ↑ Silverglat MJ (2004-10-01), Letters to the editor: No free lunch Archived 2006-06-29 at the Wayback Machine . Psychiatric News. Volume 39 Issues 19 Page 37. American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- ↑ Yamey G (2001-01-13), Pen “amnesty” for doctors who shun drug companies. BMJ: British Medical Journal. Volume 322, Issue 7278, Page 69. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- ↑ Sibbald B (2001-02-20), Doctors asked to take pledge to shun drug company freebies. Canadian Medical Association Journal. Volume 164, Issue 4. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- ↑ Rawe J (2002-10-27), No free golf. Time. Retrieved on 2007-10-07.

- ↑ Ray Moynihan (2003-05-31), Who pays for the pizza? Redefining the relationships between doctors and drug companies. 2: Disentanglement. BMJ: British Medical Journal. Volume 326, Issue 7400, Pages 1193–1196. Retrieved on 2007-10-06.

- ↑ Ray Moynihan (2003-05-31). Drug company sponsorship of education could be replaced at a fraction of its cost. BMJ: British Medical Journal, Volume 326, Issue 7400, Page 1163. Retrieved on 2007-10-07.