Related Research Articles

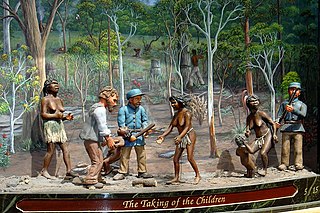

The Stolen Generations were the children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments. The removals of those referred to as "half-caste" children were conducted in the period between approximately 1905 and 1967, although in some places mixed-race children were still being taken into the 1970s.

Albert Namatjira was a Arrernte painter from the MacDonnell Ranges in Central Australia, widely considered one of the greatest and most influential Australian artists. As a pioneer of contemporary Indigenous Australian art, he was arguably one of the most famous Indigenous Australians of his generation. He was the first Aboriginal artist to receive popularity from a wide Australian audience.

The second question of the 1967 Australian referendum of 27 May 1967, called by the Holt Government, related to Indigenous Australians. Voters were asked whether to give the Federal Government the power to make special laws for Indigenous Australians in states, and whether in population counts for constitutional purposes to include all Indigenous Australians. The term "the Aboriginal Race" was used in the question.

The Wave Hill walk-off, also known as the Gurindji strike, was a walk-off and strike by 200 Gurindji stockmen, house servants and their families, starting on 23 August 1966 and lasting for seven years. It took place at Wave Hill, a cattle station in Kalkarindji, Northern Territory, Australia, and was led by Gurindji man Vincent Lingiari.

Aboriginal Protection Board, also known as Aborigines Protection Board, Aborigines Welfare Board, Board for the Protection of Aborigines and similar names, refers to a number of historical Australian state-run institutions with the function of regulating the lives of Aboriginal Australians. They were also responsible for administering the various half-caste acts where these existed and had a key role in the Stolen Generations. The boards had nearly ultimate control over Aboriginal people's lives.

The office of the Protector of Aborigines was established pursuant to a recommendation contained in the Report of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Aboriginal Tribes, of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Aboriginal Tribes. On 31 January 1838, Lord Glenelg, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies sent Governor Gipps the report. The office of Chief Protector of Aborigines was established in some states, and in Queensland the title was Protector of Aboriginals.

In Kruger v Commonwealth, also known as the Stolen Generation Case, the High Court of Australia rejected a challenge to the validity of legislation applying in the Northern Territory between 1918 and 1957 which authorised the removal of Aboriginal children from their families. The majority of the bench found that the Aboriginals Ordinance 1918 was beneficial in intent and had neither the purpose of genocide nor that of restricting the practice of religion. The High Court unanimously held there was no separate action for a breach of any constitutional right.

The Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897, long name A Bill to make Provision for the better Protection and Care of the Aboriginal and Half-caste Inhabitants of the Colony, and to make more effectual Provision for Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Opium, was an Act of the Parliament of Queensland. It was the first instrument of separate legal control over Aboriginal peoples, and was more restrictive than any contemporary legislation operating in other states. It also implemented the creation of Aboriginal reserves to control the dwelling places and movement of the people.

Aboriginal Affairs NSW (AANSW) is an agency of the Department of Premier and Cabinet in the Government of New South Wales. Aboriginal Affairs NSW is responsible for administering legislation in relation to the NSW Government policies that support Indigenous Australians in New South Wales, and for advising the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Don Harwin.

The history of the Aboriginal inhabitants of Western Australia has been dated as existing for 50-70 thousand years before European contact. This article only deals with documented history from non indigenous sources since European settlement in Perth.

The voting rights of Indigenous Australians became an issue from the mid-19th century, when responsible government was being granted to Britain's Australian colonies, and suffrage qualifications were being debated. The resolution of universal rights progressed into the mid-20th century.

The Northern Territory National Emergency Response, also known as "The Intervention" or the Northern Territory Intervention, and sometimes the abbreviation "NTER" was a package of measures enforced by legislation affecting Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory (NT) of Australia. The measures included restrictions on the consumption of alcohol and pornography, changes to welfare payments, and changes to the delivery and management of education, employment and health services in the Territory.

Half-Caste Act was the common name given to Acts of Parliament passed in Victoria and Western Australia in 1886. They became the model for legislation to control Aboriginal people throughout Australia, such as the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 in Queensland.

This is a timeline of Aboriginal history of Western Australia.

William Harris (1867–1931) was an early Western Australian activist for Aboriginal civil rights. He has been called "the most significant voice of a generation with the education and social standing to assert their rights as British subjects".

Commonwealth, State, and Territory Parliaments of Australia have passed Aboriginal land rights legislation.

An Aboriginal reserve, also called simply reserve, was a government-run settlement for Aboriginal Australians, created under various state and federal legislation. Along with missions and other institutions, they were used from the 19th century to the 1960s to keep Aboriginal people separate from the white Australian population, for various reasons perceived by the government of the day. The Aboriginal reserve laws gave governments much power over all aspects of Aboriginal people’s lives.

The Aborigines Protection Act 1909 was a New South Wales statute that repealed the Supply of Liquors to Aborigines Prevention Act 1867 with the aim of providing for the protection and care of Aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia. The Act gave the Board for the Protection of Aborigines control of the Aboriginal reserves in New South Wales and the lives of the people who lived on the reserves. Amendments to the Act in 1915 gave the Aborigines Protection Board in New South Wales broad powers to remove Aboriginal children from their families, resulting in the Stolen Generations.

The Council for Aboriginal Rights (CAR) was founded in Melbourne in 1951 in order to improve rights for Indigenous Australians. Although based in the state of Victoria, it was a national organisation and its influence was felt throughout Australia; it was regarded as one of the most important Indigenous rights organisations of the 1950s. It supported causes in several other states, notably Western Australia and Queensland, and the Northern Territory. Some of its members went on to be important figures in other Indigenous rights organisations.

References

- ↑ "The Northern Territory Aboriginals Act (No 1024 of 1910)". Australasian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ↑ Walker, David (1999). Anxious Nation: Australia and the Rise of Asia, 1850–1939. University of Queensland Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0702231315.

- ↑ Chapter 13 Grounds for Reparation. Bringing them home. Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. April 1997. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ↑ "Aboriginals Ordinance No. 9 of 1918 (Cth)". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ↑ George, Karen; George, Gary (24 September 2014). "Aboriginals Ordinance 1918 (1918 - 1953)". Find & Connect. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ↑ "The History: Northern Territory" (PDF). Sydney, Australia: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. December 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2008.

- 1 2 "Aboriginals Ordinance 1953 (Legislation – Northern Territory)". Find & Connect. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- 1 2 McGregor, Russell (December 2005). "Avoiding "Aborigines": Paul Hasluck and the Northern Territory Welfare Ordinance, 1953 [Abstract]". Australian Journal of Politics and History . Wiley. 51 (4): 513–529. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.2005.00391.x. ISSN 0004-9522.

- 1 2 3 4 George, Karen; Moje, Christine (11 October 2017). "Welfare Ordinance 1953 (1957-1964) (Legislation – Northern Territory)". Find & Connect. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Summers, John (31 October 2000). "The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia and Indigenous Peoples 1901–1967". Parliament of Australia . Research Paper 10 2000–01. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ "Appendix 7: Northern Territory". Bringing them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. April 1997. Retrieved 1 December 2020– via Australian Human Rights Commission.

- ↑ Taffe, Sue (11 April 2014). "Essay – The Council for Aboriginal Rights (Victoria)". Australian Dictionary of Biography . Australian National University . Retrieved 1 December 2020.