Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus, often Anglicized as Galen and sometimes known as Galen of Pergamon, was a physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered one of the most accomplished of all medical researchers of antiquity, Galen influenced the development of various scientific disciplines, including anatomy, physiology, pathology, pharmacology, and neurology, as well as philosophy and logic.

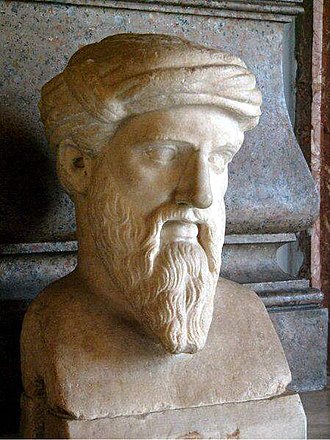

Hippocrates of Kos, also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the Age of Pericles, who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is often referred to as the "Father of Medicine" in recognition of his lasting contributions to the field as the founder of the Hippocratic School of Medicine. This intellectual school revolutionized Ancient Greek medicine, establishing it as a discipline distinct from other fields with which it had traditionally been associated, thus establishing medicine as a profession.

Herophilos, sometimes Latinised Herophilus, was a Greek physician deemed to be among the earliest anatomists. Born in Chalcedon, he spent the majority of his life in Alexandria. He was the first scientist to systematically perform scientific dissections of human cadavers. He recorded his findings in over nine works, which are now all lost. The early Christian author Tertullian states that Herophilos vivisected at least 600 live prisoners; however, this account has been disputed by many historians.

Humourism, the humoural theory or humouralism, was a system of medicine detailing the makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

The Hippocratic Corpus, or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. The Hippocratic Corpus covers many diverse aspects of medicine, from Hippocrates' medical theories to what he devised to be ethical means of medical practice, to addressing various illnesses. Even though it is considered as a singular corpus that represents Hippocratic medicine, they vary in content, age, style, methods, and views practiced; therefore, authorship is largely unknown. Hippocrates began Western society's development of medicine, through a delicate blending of the art of healing and scientific observations. What Hippocrates was sharing from within his collection of works was not only how to identify symptoms of disease and proper diagnostic practices, but more essentially, he was eluding to his own form of art, "The art of true living and the art of fine medicine combined." The Hippocratic Corpus became the foundation for which all future Western medical systems would be built.

Asclepiades, sometimes called Asclepiades of Bithynia or Asclepiades of Prusa, was a Greek physician born at Prusias-on-Sea in Bithynia in Asia Minor and who flourished at Rome, where he practised and taught Greek medicine. He attempted to build a new theory of disease, based on the flow of atoms through pores in the body. His treatments sought to restore harmony through the use of diet, exercise, and bathing.

Alcmaeon of Croton has been described as one of the most eminent natural philosophers and medical theorists of antiquity. He has been referred to as "a thinker of considerable originality and one of the greatest philosophers, naturalists, and neuroscientists of all time." His work in biology has been described as remarkable, and his originality made him likely a pioneer. Because of difficulties dating Alcmaeon's birth, his importance has been neglected.

The medicine of the ancient Egyptians is some of the oldest documented. From the beginnings of the civilization in the late fourth millennium BC until the Persian invasion of 525 BC, Egyptian medical practice went largely unchanged and included simple non-invasive surgery, setting of bones, dentistry, and an extensive set of pharmacopoeia. Egyptian medical thought influenced later traditions, including the Greeks.

Diocles of Carystus was a well-regarded Greek physician, born in Carystus, a city on Euboea, Greece. His significance was as a major thinker, practitioner, and writer of the fourth century.

Helen King is a British classical scholar. She is Professor Emerita of Classical Studies at the Open University. She was previously Professor of the History of Classical Medicine and Head of the Department of Classics at the University of Reading.

Ancient Greek medicine was a compilation of theories and practices that were constantly expanding through new ideologies and trials. Many components were considered in ancient Greek medicine, intertwining the spiritual with the physical. Specifically, the ancient Greeks believed health was affected by the humors, geographic location, social class, diet, trauma, beliefs, and mindset. Early on the ancient Greeks believed that illnesses were "divine punishments" and that healing was a "gift from the Gods". As trials continued wherein theories were tested against symptoms and results, the pure spiritual beliefs regarding "punishments" and "gifts" were replaced with a foundation based in the physical, i.e., cause and effect.

Medicine in ancient Rome combined various techniques using different tools, methodology, and ingredients. Ancient Roman medicine was highly influenced by Greek medicine but would ultimately have its own contribution to the history of medicine through past knowledge of the Hippocratic Corpus combined with use of the treatment of diet, regimen, along with surgical procedures. This was most notably seen through the works of two of the prominent Greek Physicians, including Dioscorides and Galen, who practiced medicine and recorded their discoveries in the Roman Empire. This is contrary to two other physicians like Soranus of Ephesus and Asclepiades of Bithynia who practiced medicine both in outside territories and in ancient Roman territory, subsequently. Dioscorides was a Roman army physician, Soranus was a representative for the Methodic school of medicine, Galen performed public demonstrations, and Asclepiades was a leading Roman physician. These four physicians all had knowledge of medicine, ailments, and treatments that were healing, long lasting and influential to human history.

Pneuma (πνεῦμα) is an ancient Greek word for "breath", and in a religious context for "spirit" or "soul". It has various technical meanings for medical writers and philosophers of classical antiquity, particularly in regard to physiology, and is also used in Greek translations of ruach רוח in the Hebrew Bible, and in the Greek New Testament. In classical philosophy, it is distinguishable from psyche (ψυχή), which originally meant "breath of life", but is regularly translated as "spirit" or most often "soul".

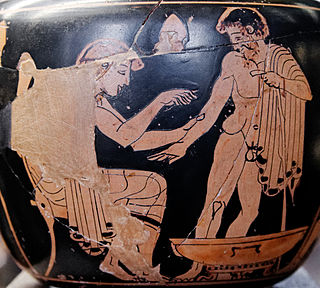

Childbirth and obstetrics in Classical Antiquity were studied by the physicians of ancient Greece and Rome. Their ideas and practices during this time endured in Western medicine for centuries and many themes are seen in modern women's health. Gynecology and obstetrics were originally studied and taught mainly by midwives in the ancient world, but eventually scholarly physicians of both sexes became involved as well. Obstetrics is traditionally defined as the surgical specialty dealing with the care of a woman and her offspring during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (recovery). Gynecology involves the medical practices dealing with the health of women's reproductive organs and their breasts.

The Methodic school of medicine was a school of medicine in ancient Greece and Rome. The Methodic school arose in reaction to both the Empiric school and the Dogmatic school. While the exact origins of the Methodic school are shrouded in some controversy, its doctrines are fairly well documented. Sextus Empiricus points to the school's common ground with Pyrrhonism, in that it “follow[s] the appearances and take[s] from these whatever seems expedient.”

Palladius a Greek medical writer, some of whose works are still extant. Nothing is known of the events of his life, but, as he is commonly called Iatrosophistes, he is supposed to have gained that title by having been a professor of medicine at Alexandria. His date is uncertain; he may lived in the 6th or 7th centuries. All that can be pronounced with certainty is that he quotes Galen, and is himself quoted by Rhazes. Three of his works are extant:

Peter David Arthur Garnsey, is a retired British classicist and academic. He was a fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge from 1974 to 2006, and a professor of the history of classical antiquity at the University of Cambridge from 1997 to 2006. His area of research concerns the history of political theory, intellectual history, social and economic history, food, famine and nutrition, and physical anthropology.

Food and dining in the Roman Empire reflect both the variety of food-stuffs available through the expanded trade networks of the Roman Empire and the traditions of conviviality from ancient Rome's earliest times, inherited in part from the Greeks and Etruscans. In contrast to the Greek symposium, which was primarily a drinking party, the equivalent social institution of the Roman convivium was focused on food. Banqueting played a major role in Rome's communal religion. Maintaining the food supply to the city of Rome had become a major political issue in the late Republic, and continued to be one of the main ways the emperor expressed his relationship to the Roman people and established his role as a benefactor. Roman food vendors and farmers' markets sold meats, fish, cheeses, produce, olive oil and spices; and pubs, bars, inns and food stalls sold prepared food.

Grape syrup is a condiment made with concentrated grape juice. It is thick and sweet because of its high ratio of sugar to water. Grape syrup is made by boiling grapes, removing their skins, squeezing them through a sieve to extract the juice, and adding sugar. Like other fruit syrups, a common use of grape syrup is as a topping to sweet cakes, such as pancakes or waffles.

Modern understanding of disease is very different from the way it was understood in ancient Greece and Rome. The way modern physicians approach healing of the sick differs greatly from the methods used by early general healers or elite physicians like Hippocrates or Galen. In modern medicine, the understanding of disease stems from the “germ theory of disease”, a concept that emerged in the second half of the 19th century, such that a disease is the result of an invasion of a microorganism into a living host. Therefore, when a person becomes ill, modern treatments “target” the specific pathogen or bacterium in order to “beat” or “kill” the disease. In Ancient Greece and Rome, disease was literally understood as dis-ease, or physical imbalance. Medical intervention, therefore, was purposed with goal of restoration of harmony rather than waging a war against disease. Surgery was regarded by Greek and Roman physicians as extreme and damaging while prevention was seen as the crucial first step to healing almost all ailments. In both prevention and treatment of disease in classical medicine, food and diet was central. The eating of correctly-balanced foods made up the majority of preventative treatment as well as to restore harmony to the body after it encountered disease.