A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, rites of sacrifice to, and propitiation of, a deity or deities. Their office or position is the "priesthood", a term which also may apply to such persons collectively. A priest may have the duty to hear confessions periodically, give marriage counseling, provide prenuptial counseling, give spiritual direction, teach catechism, or visit those confined indoors, such as the sick in hospitals and nursing homes.

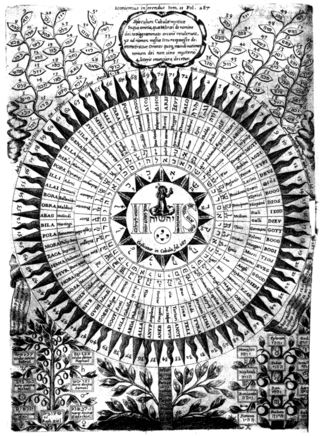

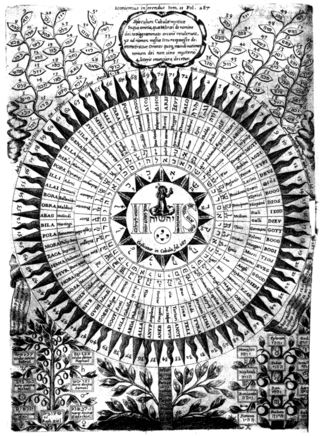

Sacred geometry ascribes symbolic and sacred meanings to certain geometric shapes and certain geometric proportions. It is associated with the belief of a divine creator of the universal geometer. The geometry used in the design and construction of religious structures such as churches, temples, mosques, religious monuments, altars, and tabernacles has sometimes been considered sacred. The concept applies also to sacred spaces such as temenoi, sacred groves, village greens, pagodas and holy wells, Mandala Gardens and the creation of religious and spiritual art.

In ancient Egyptian religion, Apis or Hapis, alternatively spelled Hapi-ankh, was a sacred bull or multiple sacred bulls worshiped in the Memphis region, identified as the son of Hathor, a primary deity in the pantheon of ancient Egypt. Initially, he was assigned a significant role in her worship, being sacrificed and reborn. Later, Apis also served as an intermediary between humans and other powerful deities.

Odinani, also known as Odinala, Omenala, Odinana, and Omenana, is the traditional cultural belief and practice of the Igbo people of south east and Igbo people of south south Nigeria. These terms, as used here in the Igbo language, are synonymous with the traditional Igbo "religious system" which was not considered separate from the social norms of ancient or traditional Igbo societies. Theocratic in nature, spirituality played a huge role in their everyday lives. Although it has largely been syncretised with Catholicism, the indigenous belief system remains in strong effect among the rural, village and diaspora populations of the Igbo. Odinani can be found in Haitian Voodoo, Obeah, Santeria and even Candomblé. Odinani is a pantheistic and polytheistic faith, having a strong central deity at its head. All things spring from this deity. Although a pantheon of other gods and spirits, these being Ala, Amadiọha, Anyanwụ, Ekwensu, Ikenga, exists in the belief system, as it does in many other Traditional African religions, the lesser deities prevalent in Odinani serve as helpers or elements of Chukwu, the central deity.

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or revered objects. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, but not defined, by formalism, traditionalism, invariance, rule-governance, sacral symbolism, and performance.

Anthropology of religion is the study of religion in relation to other social institutions, and the comparison of religious beliefs and practices across cultures. The anthropology of religion, as a field, overlaps with but is distinct from the field of Religious Studies. The history of anthropology of religion is a history of striving to understand how other people view and navigate the world. This history involves deciding what religion is, what it does, and how it functions. Today, one of the main concerns of anthropologists of religion is defining religion, which is a theoretical undertaking in and of itself. Scholars such as Edward Tylor, Emile Durkheim, E.E. Evans Pritchard, Mary Douglas, Victor Turner, Clifford Geertz, and Talal Asad have all grappled with defining and characterizing religion anthropologically.

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has been questioned as anachronistic. The ancient Greeks did not have a word for 'religion' in the modern sense. Likewise, no Greek writer known to us classifies either the gods or the cult practices into separate 'religions'. Instead, for example, Herodotus speaks of the Hellenes as having "common shrines of the gods and sacrifices, and the same kinds of customs."

There are various names of God, many of which enumerate the various qualities of a Supreme Being. The English word god is used by multiple religions as a noun to refer to different deities, or specifically to the Supreme Being, as denoted in English by the capitalized and uncapitalized terms God and god. Ancient cognate equivalents for the biblical Hebrew Elohim, one of the most common names of God in the Bible, include proto-Semitic El, biblical Aramaic Elah, and Arabic ilah. The personal or proper name for God in many of these languages may either be distinguished from such attributes, or homonymic. For example, in Judaism the tetragrammaton is sometimes related to the ancient Hebrew ehyeh. It is connected to the passage in Exodus 3:14 in which God gives his name as אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה, where the verb may be translated most basically as "I am that I am", "I shall be what I shall be", or "I shall be what I am". In the passage, YHWH, the personal name of God, is revealed directly to Moses.

Traditional Sámi spiritual practices and beliefs are based on a type of animism, polytheism, and what anthropologists may consider shamanism. The religious traditions can vary considerably from region to region within Sápmi.

Chinese folk religion comprises a range of traditional religious practices of Han Chinese, including the Chinese diaspora. This includes the veneration of shen ('spirits') and ancestors, and worship devoted to deities and immortals, who can be deities of places or natural phenomena, of human behaviour, or progenitors of family lineages. Stories surrounding these gods form a loose canon of Chinese mythology. By the Song dynasty (960–1279), these practices had been blended with Buddhist, Confucian, and Taoist teachings to form the popular religious system which has lasted in many ways until the present day. The government of China generally tolerates popular religious organizations, but has suppressed or persecuted those that they fear would undermine social stability.

Nnewi is a commercial and industrial city in Anambra State, southeastern Nigeria. It is the second largest city in Anambra state after Onitsha. Nnewi as a metropolitan area has two local government area, which are Nnewi North and Nnewi South, all centred around the Nnewi town. Even Ekwusigo local government area is now part of Nnewi urban area, as urbanization continues to spread from Nnewi to neighbouring communities. The Nnewi town which is the only town in Nnewi North, comprises four villages: Otolo, Uruagu, Umudim, and Nnewichi. Nnewi had been the centre of economics and commerce, being at a time the fastest growing industrial city east of the Niger, being the home of many industries such as The Ibeto Group, the Chicason Group, Cutix Cables, amongst others. The first indigenous car manufacturing plant in Nigeria is located in the city while the first wholly Made-in-Nigeria motorcycle, the 'NASENI M1' was manufactured in Nnewi.

Sexual orientation in Zoroastrianism is, as in many other religions, a controversial topic with differing consensus over time.

Indigenous Philippine folk religions are the distinct native religions of various ethnic groups in the Philippines, where most follow belief systems in line with animism. Generally, these Indigenous folk religions are referred to as Anito or Anitism or the more modern and less ethnocentric Dayawism, where a set of local worship traditions are devoted to the anito or diwata, terms which translate to Gods, spirits, and ancestors. Many of the narratives within the indigenous folk religions are orally transmitted to the next generation, but many have traditionally been written down as well. The Spanish have claimed that the natives did not have religious writings.

Ejemekwuru is an Igbo-speaking community that sits in the North-Western part of Imo State in the southeastern region of Nigeria.

Hawaiian religion refers to the indigenous religious beliefs and practices of native Hawaiians, also known as the kapu system. Hawaiian religion is based largely on the tapu religion common in Polynesia and likely originated among the Tahitians and other Pacific islanders who landed in Hawaiʻi between 500 and 1300 AD. It is polytheistic and animistic, with a belief in many deities and spirits, including the belief that spirits are found in non-human beings and objects such as other animals, the waves, and the sky. It was only during the reign of Kamehameha I that a ruler from Hawaii island attempted to impose a singular "Hawaiian" religion on all the Hawaiian islands that was not Christianity.

The Igbo calendar is the traditional calendar system of the Igbo people from present-day Nigeria. The calendar has 13 months in a year (Afọ), 7 weeks in a month (Ọnwa), and 4 days of Igbo market days in a week (Izu) plus an extra day at the end of the year, in the last month. The name of these months was reported by Onwuejeogwu (1981).

The historical origin of Ekwe is based on oral myth and legend of tradition of common ancestors passed from generation to generation. According to this oral tradition -"Nnamike Onuoma", the founder of the Ekwe community had two sons -Ekwe and Okwudor. Okwudor later separated from his brother and settled at the other side of the Njaba River and founded the Okwudor community. Ekwe stayed put in the area, which is now known as Ekwe.[1]

Over the millennia of its development, Hinduism has adopted several iconic symbols, forming part of Hindu iconography, that are imbued with spiritual meaning based on either the scriptures or cultural traditions. The exact significance accorded to any of the icons varies with region, period and denomination of the followers. Over time some of the symbols, for instance the Swastika has come to have wider association while others like Om are recognized as unique representations of Hinduism. Other aspects of Hindu iconography are covered by the terms murti, for icons and mudra for gestures and positions of the hands and body.

Afiaolu is a traditional festival held annually in Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria around August. The Afiaolu festival commences on “Eke” day with what is traditionally described as “Iwaji” and Ikpa Nku, this heralds the availability of new yam as well as thanksgiving to God. The festival includes a variety of entertainments including performance of ceremonial rites by the Igwe (king), cultural dance by girls and masquerade dance.

Ezema is one of four sub-communities that made up Nru Nsukka town in Nsukka Local Government Area, Nigeria. It is adjacent to the three other sub-communities in Nru Nsukka: Edem Nru, Umuoyo Nru and Iheagu. It also shares common boundaries with Various communities such as Umuoyo, Iheagu, Agbamere/Amike and Umabor both in Eha Alumona.