Nigeria’s transport network has expanded in recent years to accommodate a growing population. The transport and storage sector was valued at N2.6trn ($6.9bn) in current basic prices in 2020, down from N3trn ($8bn) in 2019, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). This was reflected in a lower contribution to GDP, at 1.8% in the fourth quarter of 2020, down from 2.1% during the same period the previous year but higher than the 0.8% recorded in the third quarter of 2020. One of the most significant challenges facing the sector is meeting the needs of both large coastal cities and rural inland communities in order to fully unlock the country’s economic potential. This is especially the case with mining and agriculture, both of which are expected to benefit from two large-scale projects: the Lekki Port in Lagos and the Kano-Maradi rail line in the north of the country.

Muhammadu Buhari is a Nigerian statesman who served as the president of Nigeria from 2015 to 2023. A retired Nigerian Army major general, he served as the country's military head of state from 31 December 1983 to 27 August 1985, after taking power from the Shehu Shagari civilian government in a military coup d'état. The term Buharism is used to describe the authoritarian policies of his military regime.

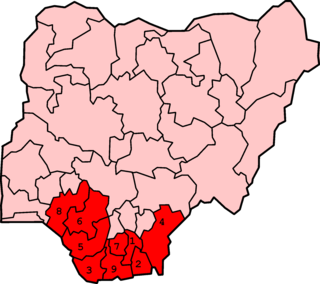

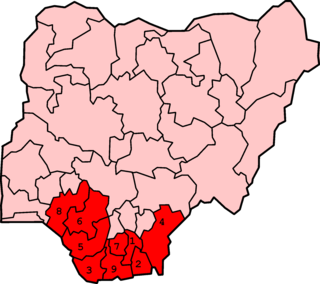

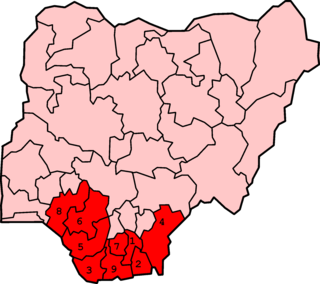

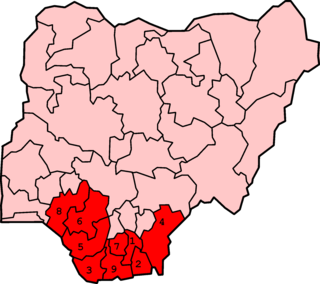

The Niger Delta is the delta of the Niger River sitting directly on the Gulf of Guinea on the Atlantic Ocean in Nigeria. It is located within nine coastal southern Nigerian states, which include: all six states from the South South geopolitical zone, one state (Ondo) from South West geopolitical zone and two states from South East geopolitical zone.

Singapore Petroleum Company Limited, in short SPC, is a Singaporean multinational oil and gas company. It is involved in the exploration and production of petroleum, refining, trading and petroleum product distribution.

Okrika is an island in Rivers State, Nigeria, capital of the Local Government Area of the same name. The town is situated on an island south of Port Harcourt, making it a suburb of the much larger city.

Nigeria is the second largest oil and gas producer in Africa. Crude oil from the Niger Delta basin comes in two types: light, and comparatively heavy – the lighter has around 36 of API gravity while the heavier has 20–25 of API gravity. Both types are paraffinic and low in Sulphur. Nigeria's economy and budget have been largely supported from income and revenues generated from the petroleum industry since 1960. Statistics as at February 2021 shows that the Nigerian oil sector contributes to about 9% of the GDP of the nation.

The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) is a decentralised militant group in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. MEND's actions – including sabotage, theft, property destruction, guerrilla warfare, and kidnapping – are part of the broader conflict in the Niger Delta and reduced Nigeria's oil production by 33% between 2006-07.

Shell Nigeria is the common name for Shell plc's Nigerian operations carried out through four subsidiaries—primarily Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Limited (SPDC). Royal Dutch Shell's joint ventures account for more than 21% of Nigeria's total petroleum production.

Asari-Dokubo, formerly Melford Dokubo Goodhead Jr. and typically referred to simply as Asari, is a major political figure of the Ijaw ethnic group in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. He was president of the Ijaw Youth Council for a time beginning in 2001 and later founded the Niger Delta People's Volunteer Force which would become one of the most prominent armed groups operating in the Niger Delta region. He is a Muslim with populist views and an anti-government stance that have made him a folk hero amongst certain members of the local population.

The current conflict in the Niger Delta first arose in the early 1990s over tensions between foreign oil corporations and a number of the Niger Delta's minority ethnic groups who feel they are being exploited, particularly the Ogoni and the Ijaw. Ethnic and political unrest continued throughout the 1990s despite the return to democracy and the election of the Obasanjo government in 1999. Struggle for oil wealth and environmental harm over its impacts has fueled violence between ethnic groups, causing the militarization of nearly the entire region by ethnic militia groups, Nigerian military and police forces, notably the Nigerian Mobile Police. The violence has contributed to Nigeria's ongoing energy supply crisis by discouraging foreign investment in new power generation plants in the region.

Environmental issues in the Niger Delta are caused by its petroleum industry. The delta covers 20,000 km2 (7,700 sq mi) within wetlands of 70,000 km2 (27,000 sq mi) formed primarily by sediment deposition. Home to 20 million people and 40 different ethnic groups, this floodplain makes up 7.5% of Nigeria's total land mass. It is the largest wetland and maintains the third-largest drainage basin in Africa. The Delta's environment can be broken down into four ecological zones: coastal barrier islands, mangrove swamp forests, freshwater swamps, and lowland rainforests. Fishing and farming are the main sources of livelihoods for majority of her residents.

The Warri Crisis was a series of conflicts in Delta State, Nigeria between 1997 and 2003 between the Itsekiri, the Ijaw ethnic groups. Over 200,000 people were displaced by the Warri conflict between 1999 and 2006. Over 700,000 people were displaced during this period by violence in Delta State overall.

Government Oweizide Ekpemupolo predominantly referred to by his sobriquet Tompolo is a former Nigerian militant commander of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta and the chief priest of the Egbesu deity, which is the Ijaw god of war.

Nembe Creek Trunk Line (NCTL) is a 97 kilometre, 150,000 barrels of oil per day pipeline constructed by Royal Dutch Shell plc and situated in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. "The Trunk Line is one of Nigeria's major oil transportation arteries that evacuate crude from the Niger Delta to the Atlantic coast for export." It is owned by Aiteo Group, which recently purchased it as part of the related facilities of the prolific oil bloc OML29 from Shell Petroleum Development Company, SPDC. By March 2015, the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Limited (SPDC), a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell plc (Shell), completed the assignment of its interest in OML29 and the Nembe Creek Trunk Line to Aiteo Eastern E&P Company Limited, a subsidiary of Aiteo Group. The other joint venture partners, Total E&P Nigeria Limited and Nigerian Agip Oil Company Limited also assigned their interests of 10% and 5% respectively in the lease, ultimately giving Aiteo Eastern E&P Company Limited a 45% interest in OML29 and the Nembe Creek Trunk Line.

The Niger Delta Avengers (NDA) is a militant group in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. The group publicly announced their existence in March 2016.

The 2016Niger Delta conflict is an ongoing conflict around the Niger Delta region of Nigeria in a bid for the secession of the region, which was a part of the breakaway state of Biafra. It follows on-and-off conflict in the Christian-dominated southern Niger Delta in the preceding years, as well as an insurgency in the Muslim-dominated northeast.

The Niger Delta Greenland Justice Mandate (NDGJM) is a militant group operating in Nigeria's Niger Delta region. The group was founded on August 2, 2016 in Delta State and is composed mainly of ethnic Urhobos, and a fairly large number of members belonging to the Isoko ethnic group.

The Dangote Refinery is an oil refinery owned by Dangote Group that was inaugurated on 22 May 2023 in Lekki, Nigeria. When fully operational, it is expected to have the capacity to process about 650,000 barrels of crude oil per day, making it the largest single-train refinery in the world. The investment is over US$19 billion.

As a practice of piracy, petro-piracy, also sometimes called oil piracy or petrol piracy, is defined as “illegal taking of oil after vessel hijacks, which are sometimes executed with the use of motorships” with huge potential financial rewards. Petro-piracy is mostly a practice that is connected to and originates from piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, but examples of petro-piracy outside of the Gulf of Guinea is not uncommon. At least since 2008, the Gulf of Guinea has been home to pirates practicing petro-piracy by targeting the region's extensive oil industry. Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea has risen in the last years to become the hot spot of piracy globally with 76 actual and attempted attacks, according to the International Maritime Bureau (IMB). Most of these attacks in the Gulf of Guinea take place in inland or territorial waters, but recently pirates have been proven to venture further out to sea, e.g. crew members were kidnapped from the tanker David B. 220 nautical miles outside of Benin. Pirates most often targets vessels carrying oil products and kidnappings of crew for ransom. IMB reports that countries in the Gulf of Guinea, Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Togo, Congo, and, especially, Nigeria, have experienced petro-piracy and kidnappings of crew as the most common trends of piracy attacks in the Gulf of Guinea.

Piracy network in Nigeria refers to the organisation of actors involved in the sophisticated, complex piracy activities: piracy kidnappings and petro-piracy. The most organised piracy activities in the Gulf of Guinea takes place in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. A large number of both non-state and formal state actors are involved in a piracy operation, indicating a vast social network. As revealed by the arrested pirate Bless Nube “we do not work in isolation. We have a network of ministries’ workers. What they do is to give us information on the location and content of the vessels to be hijacked. After furnishing us with the information, they would make part payment, and after the hijack, they would pay us the balance.” Pirate groups draw on the pirate network to gain access to actors who provide security, economic resources, and support to pirate operations. This includes government officials, businesspeople, armed groups, and transnational mafia.