Related Research Articles

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States government for the relocation of Native Americans who held original Indian title to their land as a sovereign independent state. The concept of an Indian territory was an outcome of the U.S. federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), the policy of the U.S. government was one of assimilation.

Osage County is the largest county by area in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Created in 1907 when Oklahoma was admitted as a state, the county is named for and is home to the federally recognized Osage Nation. The county is coextensive with the Osage Nation Reservation, established by treaty in the 19th century when the Osage relocated there from Kansas. The county seat is in Pawhuska, one of the first three towns established in the county. The total population of the county as of 2020 was 45,818.

Burbank is a town in western Osage County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 141 at the 2010 census, a 9 percent decrease from the figure of 155 recorded in 2000.

The Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936 is a United States federal law that extended the 1934 Wheeler-Howard or Indian Reorganization Act to include those tribes within the boundaries of the state of Oklahoma. The purpose of these acts were to rebuild Indian tribal societies, return land to the tribes, enable tribes to rebuild their governments, and emphasize Native culture. These Acts were developed by John Collier, Commissioner of Indian Affairs from 1933 to 1945, who wanted to change federal Indian policy from the "twin evils" of allotment and assimilation, and support Indian self-government.

The Osage Indian murders were a series of murders of Osage in Osage County, Oklahoma, during the 1910s–1930s. Newspapers described the increasing number of unsolved murders and deaths among young adults as the "Reign of Terror". Most took place from 1921 to 1926. Some sixty or more wealthy, full-blood Osage persons were reported killed from 1918 to 1931. Newer investigations indicate that other suspicious deaths during this time could have been misreported or covered-up murders, including those of individuals who were heirs to future fortunes. Further research has shown that the death toll may have been in the hundreds.

The Osage Nation, is a Midwestern American tribe of the Great Plains. The tribe developed in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys around 700 B.C. along with other groups of its language family. They migrated west after the 17th century, settling near the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers, as a result of Iroquois expansion into the Ohio Country in the aftermath of the Beaver Wars.

Blood quantum laws or Indian blood laws are laws in the United States that define Native American status by fractions of Native American ancestry. These laws were enacted by the federal government and state governments as a way to establish legally defined racial population groups. By contrast, many tribes do not include blood quantum as part of their own enrollment criteria.

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma is a Native American territory covering about 6,952,960 acres, occupying portions of southeastern Oklahoma in the United States. The Choctaw Nation is the third-largest federally recognized tribe in the United States and the second-largest Indian reservation in area after the Navajo. As of 2011, the tribe has 223,279 enrolled members, of whom 84,670 live within the state of Oklahoma and 41,616 live within the Choctaw Nation's jurisdiction. A total of 233,126 people live within these boundaries, with its tribal jurisdictional area comprising 10.5 counties in the state, with the seat of government being located in Durant, Oklahoma. It shares borders with the reservations of the Chickasaw, Muscogee, and Cherokee, as well as the U.S. states of Texas and Arkansas. By area, the Choctaw Nation is larger than eight U.S. states.

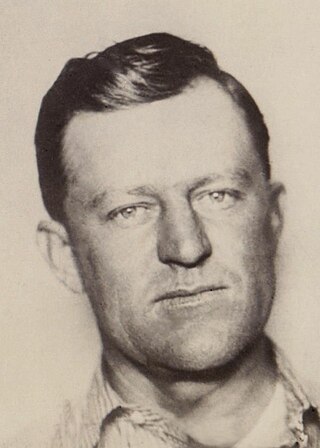

William King Hale was an American political and crime boss in Osage County, Oklahoma, who was responsible for the Osage Indian murders, for which he was later convicted. He made a fortune through cattle ranching, contract killings, and insurance fraud.

The Cherokee Nation, also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It includes people descended from members of the Old Cherokee Nation who relocated, due to increasing pressure, from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokee who were forced to relocate on the Trail of Tears. The tribe also includes descendants of Cherokee Freedmen, Absentee Shawnee, and Natchez Nation. As of 2023, over 450,000 people were enrolled in the Cherokee Nation.

John Joseph Mathews became one of the Osage Nation's most important spokespeople and writers of the mid-20th century, and served on the Osage Tribal Council from 1934 to 1942. Mathews was born into an influential Osage family, the son of William Shirley Mathews an Osage Nation tribal councilor. He studied at the University of Oklahoma, Oxford University, and the University of Geneva and served as a pilot during World War I.

The Cherokee Freedmen controversy was a political and tribal dispute between the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen regarding the issue of tribal membership. The controversy had resulted in several legal proceedings between the two parties from the late 20th century to August 2017.

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands. Official languages include Muscogee, Yuchi, Natchez, Alabama, and Koasati, with Muscogee retaining the largest number of speakers. They commonly refer to themselves as Este Mvskokvlke. Historically, they were often referred to by European Americans as one of the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast.

The Choctaw freedmen are former enslaved African Americans who were emancipated and granted citizenship in the Choctaw Nation after the Civil War, according to the tribe's new peace treaty with the United States. The term also applies to their contemporary descendants.

Sundown is a 1934 novel by the Osage writer John Joseph Mathews. Set in the Osage Nation and Osage County, Oklahoma, the novel follows the life of a "mixed blood" Osage boy named Challenge Windzer as he navigates the conflicts between Osage traditionalism and assimilationism during the early 20th century.

An Organic Act is a generic name for a statute used by the United States Congress to describe a territory, in anticipation of being admitted to the Union as a state. Because of Oklahoma's unique history an explanation of the Oklahoma Organic Act needs a historic perspective. In general, the Oklahoma Organic Act may be viewed as one of a series of legislative acts, from the time of Reconstruction, enacted by Congress in preparation for the creation of a united State of Oklahoma. The Organic Act created Oklahoma Territory, and Indian Territory that were Organized incorporated territories of the United States out of the old "unorganized" Indian Territory. The Oklahoma Organic Act was one of several acts whose intent was the assimilation of the tribes in Oklahoma and Indian Territories through the elimination of tribes' communal ownership of property.

Both Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory contained suzerain Indian nations that had legally established boundaries. The US federal government allotted collective tribal landholdings through the allotment process before the establishment of Oklahoma as a state in 1907. Tribal jurisdictional areas replaced the tribal governments, with the exception of the Osage Nation. As confirmed by the Osage Nation Reaffirmation Act of 2004, the Osage Nation retains mineral rights to their reservation, the so-called "Underground Reservation".

United States v. Ramsey, 271 U.S. 467 (1926), was a U.S. Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the government had the authority to prosecute crimes against Native Americans (Indians) on reservation land that was still designated Indian Country by federal law. The Osage Indian Tribe held mineral rights that were worth millions of dollars. A white rancher, William K. Hale, devised a plot to kill tribal members to allow his nephew, who was married to a tribal member, to inherit the mineral rights. The tribe requested the assistance of the federal government, which sent Bureau of Investigation agents to solve the murders. Hale and several others were arrested and tried for the murders, but they claimed that the federal government did not have jurisdiction. The district court quashed the indictments, but on appeal, the Supreme Court reversed, holding that the Osage lands were Indian Country and that the federal government therefore had jurisdiction. This put an end to the Osage Indian murders.

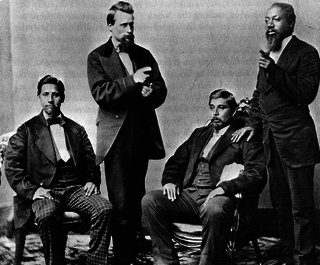

James Bigheart, also known as Big Jim, was an Osage politician who served as principal chief of the Osage Nation.

Ernest Burkhart was an American murderer who participated in the Osage Indian murders as a hitman for his uncle William King Hale's crime ring. He was convicted for the killing of William E. Smith in 1926, and sentenced to life imprisonment. Burkhart was paroled in 1937, but was sent back to prison for burglarizing his former sister-in-law's house in 1940. After being paroled for the final time in 1959, Burkhart was pardoned by Oklahoma governor Henry Bellmon in 1965 or 1966 for his role in the Osage murders.

References

- 1 2 "Frequently Asked Questions". osagenation-nsn.gov. Osage Nation. 3 June 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 Dennison, Jean (2014). "The Logic of Recognition: Debating Osage Nation Citizenship in the Twenty-First Century". American Indian Quarterly. 38 (1): 1–35. doi:10.5250/amerindiquar.38.1.0001. ISSN 0095-182X . Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 Kesler, Sam Yellowhorse; Aronczyk, Amanda; Romer, Keith; Rubin, Willa (March 24, 2023). "Blood, oil, and the Osage Nation: The battle over headrights". NPR . Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ↑ "Part 2 — Allotment, oil and headrights". Examiner-Enterprise. November 24, 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ↑ "Osage Murders". okhistory.org. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture . Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ↑ An Act: To amend certain laws relating to the Osage Tribe of Oklahoma, and for other purposes., Pub. L. 95–496

- ↑ Duty, Shannon Shaw (January 14, 2022). "Minerals Council seeks return of Osage Headrights through federal legislation". Osage News. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ↑ Herrera, Allison (May 18, 2023). "'People need to know the history': Osage citizens excited, nervous as 'Killers of the Flower Moon' hits the big screen". KOSU . Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ↑ Skibine, Alex Tallchief (2014). "Colonial Entanglement: Constituting a Twenty-First-Century Osage Nation. By Jean Dennison" (PDF). American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 38 (1). Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Non-Osage shareholders named in lawsuit". The Bigheart Times. June 19, 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- 1 2 Duty, Shannon Shaw (January 6, 2023). "Federal legislation under review to create avenue for headright return". Osage News. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 Herrera, Allison (September 20, 2023). "Oklahoma Historical Society could soon return headrights to Osage Nation". KOSU . Retrieved 11 October 2023.