Related Research Articles

The Colony of Virginia was a British, colonial settlement in North America between 1606 and 1776.

Slavery in the colonial history of the United States refers to the institution of slavery that existed in the European colonies in North America which eventually became part of the United States of America. Slavery developed due to a combination of factors, primarily the labor demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies, which had resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were targets of enslavement by European colonists during the era.

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, or imposed involuntarily as a judicial punishment. The practice has been compared to the similar institution of slavery, although there are differences.

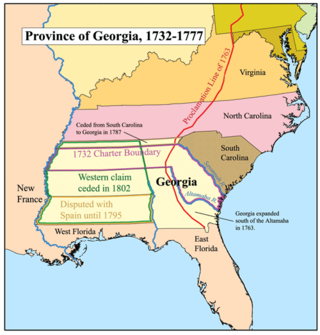

The Southern Colonies within British America consisted of the Province of Maryland, the Colony of Virginia, the Province of Carolina, and the Province of Georgia. In 1763, the newly created colonies of East Florida and West Florida would be added to the Southern Colonies by Great Britain until the Spanish Empire took back Florida. These colonies were the historical core of what would become the Southern United States, or "Dixie". They were located south of the Middle Colonies, albeit Virginia and Maryland were also called the Chesapeake Colonies.

A plantation economy is an economy based on agricultural mass production, usually of a few commodity crops, grown on large farms worked by laborers or slaves. The properties are called plantations. Plantation economies rely on the export of cash crops as a source of income. Prominent crops included Red Sandalwood, cotton, rubber, sugar cane, tobacco, figs, rice, kapok, sisal, and species in the genus Indigofera, used to produce indigo dye.

The tobacco colonies were those that lined the sea-level coastal region of English North America known as Tidewater, extending from a small part of Delaware south through Maryland and Virginia into the Albemarle Sound region of North Carolina. During the seventeenth century, the European demand for tobacco increased more than tenfold. This increased demand called for a greater supply of tobacco, and as a result, tobacco became the staple crop of the Chesapeake Bay Region.

The Somers Isles Company was formed in 1615 to operate the English colony of the Somers Isles, also known as Bermuda, as a commercial venture. It held a royal charter for Bermuda until 1684, when it was dissolved, and the Crown assumed responsibility for the administration of Bermuda as a royal colony.

John Casor, a servant in Northampton County in the Colony of Virginia, in 1655 became one of the first people of African descent in the Thirteen Colonies to be enslaved for life as a result of a civil suit.

Anthony Johnson was an Angolan-born man who achieved wealth in the early 17th-century Colony of Virginia. Held as an indentured servant in 1621, he earned his freedom after several years and was granted land by the colony.

James Pittillo was a Scots laborer and Jacobite rebel, who became a major landowner after being deported in 1716 to the Colony of Virginia. After completing service of his indenture, in 1726 Pittillo was granted 242 acres (1.0 km2) on Waqua Creek in Brunswick County, Virginia.

During the British colonization of North America, the Thirteen Colonies provided England with an outlet for surplus population as well as a new market. The colonies exported naval stores, fur, lumber and tobacco to Britain, and food for the British sugar plantations in the Caribbean. The culture of the Southern and Chesapeake Colonies was different from that of the Northern and Middle Colonies and from that of their common origin in the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Elizabeth Key Grinstead (or Greenstead) (1630 – January 20, 1665) was one of the first Black people in the Thirteen Colonies to sue for freedom from slavery and win. Key won her freedom and that of her infant son, John Grinstead, on July 21, 1656, in the Colony of Virginia.

Indentured servitude in Pennsylvania (1682-1820s): The institution of indentured servitude has a significant place in the history of labor in Pennsylvania. From the founding of the colony (1681/2) to the early post-revolution period (1820s), indentured servants contributed considerably to the development of agriculture and various industries in Pennsylvania. Moreover, Pennsylvania itself has a notable place in the broader history of indentured servitude in North America. As Cheesman Herrick stated, "This system of labor was more important to Pennsylvania than it was to any other colony or state; it continued longer in Pennsylvania than elsewhere."

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

John Punch was a Central African resident of the colony of Virginia who became its first slave. Thought to have been an indentured servant, Punch attempted to escape to Maryland and was sentenced in July 1640 by the Virginia Governor's Council to serve as a slave for the remainder of his life. Two European men who ran away with him received a lighter sentence of extended indentured servitude. For this reason, some historians consider John Punch the "first official slave in the English colonies," and his case as the "first legal sanctioning of lifelong slavery in the Chesapeake." Some historians also consider this to be one of the first legal distinctions between Europeans and Africans made in the colony, and a key milestone in the development of the institution of slavery in the United States.

Indentured servitude in continental North America began in the Colony of Virginia in 1609. Initially created as means of funding voyages for European workers to the New World, the institution dwindled over time as the labor force was replaced with enslaved Africans. Servitude became a central institution in the economy and society of many parts of colonial British America. Abbot Emerson Smith, a leading historian of indentured servitude during the colonial period, estimated that between one-half and two-thirds of all white immigrants to the British colonies between the Puritan migration of the 1630s and the American Revolution came under indenture. For the colony of Virginia, specifically, more than two-thirds of all white immigrants arrived as indentured servants or transported convict bond servants.

Indentured servitude in British America was the prominent system of labor in the British American colonies until it was eventually supplanted by slavery. During its time, the system was so prominent that more than half of all immigrants to British colonies south of New England were white servants, and that nearly half of total white immigration to the Thirteen Colonies came under indenture. By the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, only 2 to 3 percent of the colonial labor force was composed of indentured servants.

Irish indentured servants were Irish people who became indentured servants in territories under the control of the British Empire, such as the British West Indies, British North America and later Australia.

The planter class, also referred to as the planter aristocracy, was a racial and socioeconomic caste which emerged in the Americas during European colonization in the early modern period. Members of the caste, most of whom were settlers of European descent, consisted of individuals who owned or were financially connected to plantations, large-scale farms devoted to the production of cash crops in high demand across Euro-American markets. These plantations were operated by the forced labour of slaves and indentured servants and typically existed in subtropical, tropical, and somewhat more temperate climates, where the soil was fertile enough to handle the intensity of plantation agriculture. Cash crops produced on plantations owned by the planter class included tobacco, sugarcane, cotton, indigo, coffee, tea, cocoa, sisal, oil seeds, oil palms, hemp, rubber trees, and fruits. In North America, the planter class formed part of the American gentry.

William Farrar was a landowner and politician in colonial Virginia. He was a subscriber to the third charter of the Virginia Company who immigrated to the colony from England in 1618. After surviving the Jamestown massacre of 1622, he moved to Jordan's Journey. In the following year, Farrar became involved in North America's first breach of promise suit when he proposed to Cecily Jordan.

References

- ↑ Tribune-Star, Tamie DehlerSpecial to the (2012-07-08). "GENEALOGY: Headright system used to bring people into the colonies". Terre Haute Tribune-Star. Retrieved 2023-05-23.

- 1 2 "The Headright System". www.u-s-history.com. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- 1 2 3 Baird, Robert (2001). "Understanding Headrights". Bob's Genealogy Filing Cabinet II. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ↑ Hirschfelder, Arlene B. (1999). "Rolfe, John (1585–1622)". Encyclopedia of Smoking and Tobacco . Oryx Press. p. 262. ISBN 9781573562027 . Retrieved 2017-08-07.

John Rolfe, a pipe-smoking Englishman from Norfolk, Virginia, has been credited with the success of Jamestown's tobacco crop. [...] In June 1614, Rolfe shipped his first cargo of Virginia tobacco, called "Orinoco," to England.

- ↑ Eichholz, Alice (2004). Red Book: American State, County and Town Sources . Provo, UT: Ancestry. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-59331-166-7.

red book american state google books.

- ↑ "Headright System, Summary, Facts, Significance, Colonial America". American History Central. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ↑ Hilliard, Sam B. (October 1992). "Headright Grants and Surveying in Northeastern Georgia". Geographical Review. 72 (4): 416–429. doi:10.2307/214594. JSTOR 214594.

- 1 2 Gentry, Daphne (May 17, 2023). "Headrights (VA-Notes)". Virginia.gov. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- 1 2 Grymes, Charles A. "Acquiring Virginia Land By Headright'". virginiaplaces.org. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- 1 2 Morgan, Edmund S. (July 1972). "Headrights and Head Counts: A Review Article". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography . 80 (3): 361–371. JSTOR 4247736.

- ↑ Bruce, Philip Alexander [1896]. Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century: an Inquiry into the Material Condition of the People, Based upon Original and Contemporaneous Records, Volume 2 (Google EBook). New York: Macmillan and Co.

- ↑ Morgan, Edmund S. (1995). American Slavery, American Freedom: the Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: W W Norton & Co. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-393-31288-1.