Speed

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2010) |

The correct amount of sail for the conditions, with all that that implies will lead to improved boat performance compared to the over-canvassed state. [1]

A sailing boat that is carrying too much sail for the current wind conditions is said to be over-canvassed. An over-canvassed boat, whether a dinghy, a yacht or a sailing ship, is difficult to steer and control and tends to heel or roll too much. If the wind continues to rise, an over-canvassed sailing boat will become dangerous and ultimately gear may break or it may round-up into the wind, broach or capsize. Any of these eventualities puts the safety of the crew and the vessel in danger. To over-canvass a sailing boat is considered unseamanlike and imprudent. In order to reduce sail, individual sails may be lowered or furled and existing sails may be reefed. Counter-intuitively, many boats will sail faster, and certainly more smoothly, comfortably and safely, when carrying the correct amount of sail in a strong wind than they would if over-canvassed and excessively rolling, heeling, carrying too much weather helm or repeatedly rounding up.

The decision to reduce sail, to avoid being over-canvassed, is made at sea based on a number of factors. There are folklore sayings, such as, "Any fool can set a sail, but it takes a sailor to take it down" [1] and, "The best time to reef is when you first think about it; when you think it's time to shake it out, have a cup of tea first". The fact is, that the definition of being over-canvassed depends on a number of factors. These include the design, form and stability of the boat hull, [2] the age and strength of the sails and gear, the direction of the wind relative to the course, the size, experience and state of the crew, the state of the sea as well as the purpose of the voyage. [3]

Warning signs that a well-found, well-crewed sailing vessel may be over-canvassed include excessive weather helm, excessive speed, any uncontrolled rounding up or broaching, excessive slamming into or falling off of waves, excessive heel or excessive rolling. If the purpose of the journey does not include racing, or if there is any kind of damage or minor emergency on-board, or if the boat is old or if the crew is ill, or tired or short-handed, then the meaning of 'excessive' may be reduced in any of these cases.

The most important reason to avoid being over-canvassed in a blow is the safety of the boat, its gear and its crew. Frank Mulville said that, "With the wind fair a man is master of his boat and has the power to drive her as hard as he wishes – even to the point of destruction." [4] He went on to say, "In a contrary wind a well found yacht is master. She has more stamina to windward than any man by himself". Von Haeften says that, "It is impossible to tear working sails in good condition by wind pressure alone. If it happens, nevertheless, it will either be down to some sail-handling mistake so that the sail has been chafed or caught up somewhere, or to the fact that the sail was old and worn out". [5] There are many stories of gear breakage from a parted shackle leaving a sail to flap wildly to shrouds giving way to bring a mast down.

A wildly heaving deck that is heeled, rolling or broaching beyond what is normally expected, can pitch a crew member overboard into the sea, or lead to a fall and subsequent injury. Such issues of crew safety are always paramount.

A single- or short-handed crew must conserve energy and take even more care of personal safety when the boat is unlikely to be handled, or brought back for a rescue, in their absence or incapacitation. Reducing sail early and thoroughly may be more important in these cases, especially when far from land.

Friends out for a sail or a cruise, rather than a race, will be more impressed by a comfortable, stable voyage than one in which the eager skipper's personal best for angle of heel is exceeded several times.

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2010) |

The correct amount of sail for the conditions, with all that that implies will lead to improved boat performance compared to the over-canvassed state. [1]

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the water, on ice (iceboat) or on land over a chosen course, which is often part of a larger plan of navigation.

A sailboat or sailing boat is a boat propelled partly or entirely by sails and is smaller than a sailing ship. Distinctions in what constitutes a sailing boat and ship vary by region and maritime culture.

A yawl is a type of boat. The term has several meanings. It can apply to the rig, to the hull type or to the use which the vessel is put.

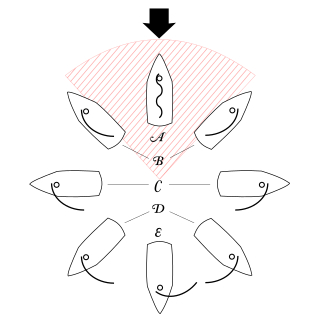

A point of sail is a sailing craft's direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface.

A jibe (US) or gybe (Britain) is a sailing maneuver whereby a sailing craft reaching downwind turns its stern through the wind, which then exerts its force from the opposite side of the vessel. It stands in contrast with tacking, whereby the sailing craft turns its bow through the wind.

The metacentric height (GM) is a measurement of the initial static stability of a floating body. It is calculated as the distance between the centre of gravity of a ship and its metacentre. A larger metacentric height implies greater initial stability against overturning. The metacentric height also influences the natural period of rolling of a hull, with very large metacentric heights being associated with shorter periods of roll which are uncomfortable for passengers. Hence, a sufficiently, but not excessively, high metacentric height is considered ideal for passenger ships.

Gaff rig is a sailing rig in which the sail is four-cornered, fore-and-aft rigged, controlled at its peak and, usually, its entire head by a spar (pole) called the gaff. Because of the size and shape of the sail, a gaff rig will have running backstays rather than permanent backstays.

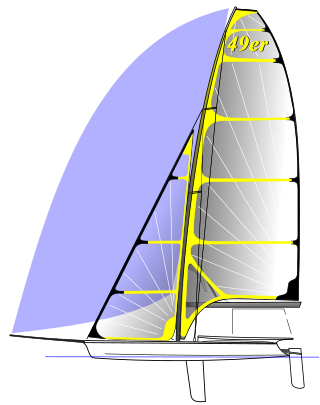

The 49er and 49er FX is a two-handed skiff-type high-performance sailing dinghy. The two crew work on different roles with the helm making many tactical decisions, as well as steering, and the crew doing most of the sail control. Both of the crew are equipped with their own trapeze and sailing is done while cantilevered over the water to the fullest extent to balance against the sails.

A broach is an abrupt, involuntary change in a vessel's course, towards the wind, resulting from loss of directional control, when the vessel's rudder becomes ineffective. This can be caused by wind or wave action. A wind gust can heel (lean) a sailing vessel, lifting its rudder out of the water. Both power and sailing vessels can broach when wave action reduces the effectiveness of the rudder. This risk occurs when traveling in the same general direction as the waves are moving. The loss of control from either cause usually leaves the vessel beam-on to the sea, and in more severe cases the rolling moment may cause a capsize.

In a keel boat, a death roll is the act of broaching to windward, putting the spinnaker pole into the water and causing a crash-jibe of the boom and mainsail, which sweep across the deck and plunge down into the water. The death roll often results in the destruction of the spinnaker pole and sometimes even the dismasting of the boat. Serious injury to crew is possible due to the swift and uncontrolled action of the boom and associated gear sweeping across the boat and crashing to the (now) leeward side.

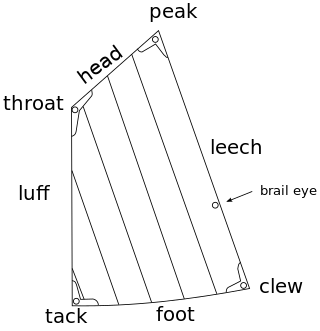

The spritsail is a four-sided, fore-and-aft sail that is supported at its highest points by the mast and a diagonally running spar known as the sprit. The foot of the sail can be stretched by a boom or held loose-footed just by its sheets. A spritsail has four corners: the throat, peak, clew, and tack. The Spritsail can also be used to describe a rig that uses a spritsail.

"Man overboard!" is an exclamation given aboard a vessel to indicate that a member of the crew or a passenger has fallen off of the ship into the water and is in need of immediate rescue. Whoever sees the person fall is to shout, "Man overboard!" and the call is then to be reported once by every crewman within earshot, even if they have not seen the victim fall, until everyone on deck has heard and given the same call. This ensures that all other crewmen have been alerted to the situation and notifies the officers of the need to act immediately to save the victim. Pointing continuously at the victim may aid the helmsman in approaching the victim.

The 18 ft Skiff is considered the fastest class of sailing skiffs. The class has a long history beginning with races on Sydney Harbour, Australia in 1892 and later in New Zealand. The boat has changed significantly since the early days, bringing in new technology as it became available. Because of the need of strength, agility and skill, the class is considered to be the top level of small boat sailing. Worldwide this boat is called the "18 Foot Skiff". It is the fastest conventional non-foiling monohull on the yardstick rating, with a score of 675, coming only third after the Tornado and Inter 20.

Rounding-up is a phenomenon that occurs in sailing when the helmsman is no longer able to control the direction of the boat and it heads up into the wind, causing the boat to slow down, stall out, or tack. This occurs when the wind overpowers the ability of the rudder to maintain a straight course.

A boat is said to be turtling or to turn turtle when it is fully inverted. The name stems from the appearance of the upside-down boat, similar to the carapace of a sea turtle. The term can be applied to any vessel; turning turtle is less frequent but more dangerous on ships than on smaller boats. It is rarer but more hazardous for multihulls than for monohulls, because multihulls are harder to flip in both directions. Measures can be taken to prevent a capsize from becoming a turtle.

In sailing, heaving to is a way of slowing a sailing vessel's forward progress, as well as fixing the helm and sail positions so that the vessel does not have to be steered. It is commonly used for a "break"; this may be to wait for the tide before proceeding, or to wait out a strong or contrary wind. For a solo or shorthanded sailor it can provide time to go below deck, to attend to issues elsewhere on the boat or to take a meal break. Heaving to can make reefing a lot easier, especially in traditional vessels with several sails. It is also used as a storm tactic.

A cruising yacht is a sailing or motor yacht that is suitable for long-distance travel and offers enough amenities to live aboard the boat, yet is small enough to not require a professional crew. A yacht that would require a professional crew enters the category of superyacht.

Weather helm is the tendency of sailing vessels to turn towards the source of wind, creating an unbalanced helm that requires pulling the tiller to windward in order to counteract the effect.

Frank Charles Dye was a sailor who, in two separate voyages, sailed a Wayfarer class dinghy from the United Kingdom to Iceland and Norway. An account of this was written by Dye and his wife, Margaret, published as Ocean Crossing Wayfarer: To Iceland and Norway in a 16ft Open Dinghy.

Forces on sails result from movement of air that interacts with sails and gives them motive power for sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and sail-powered land vehicles. Similar principles in a rotating frame of reference apply to windmill sails and wind turbine blades, which are also wind-driven. They are differentiated from forces on wings, and propeller blades, the actions of which are not adjusted to the wind. Kites also power certain sailing craft, but do not employ a mast to support the airfoil and are beyond the scope of this article.