A ship is a large vessel that travels the world's oceans and other navigable waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished from boats, based on size, shape, load capacity and purpose. Ships have supported exploration, trade, warfare, migration, colonization, and science. Ship transport is responsible for the largest portion of world commerce.

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the water, on ice (iceboat) or on land over a chosen course, which is often part of a larger plan of navigation.

Seamanship is the art, competence, and knowledge of operating a ship, boat or other craft on water. The Oxford Dictionary states that seamanship is "The skill, techniques, or practice of handling a ship or boat at sea."

A catamaran is a watercraft with two parallel hulls of equal size. The wide distance between a catamaran's hulls imparts stability through resistance to rolling and overturning; no ballast is required. Catamarans typically have less hull volume, smaller displacement, and shallower draft (draught) than monohulls of comparable length. The two hulls combined also often have a smaller hydrodynamic resistance than comparable monohulls, requiring less propulsive power from either sails or motors. The catamaran's wider stance on the water can reduce both heeling and wave-induced motion, as compared with a monohull, and can give reduced wakes.

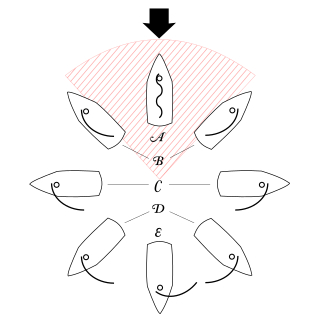

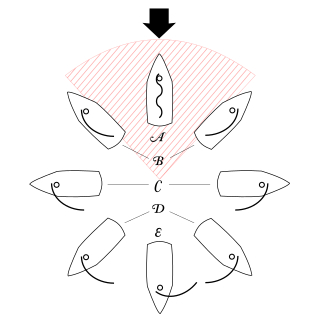

A point of sail is a sailing craft's direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface.

A jibe (US) or gybe (Britain) is a sailing maneuver whereby a sailing craft reaching downwind turns its stern through the wind, which then exerts its force from the opposite side of the vessel. It stands in contrast with tacking, whereby the sailing craft turns its bow through the wind.

The metacentric height (GM) is a measurement of the initial static stability of a floating body. It is calculated as the distance between the centre of gravity of a ship and its metacentre. A larger metacentric height implies greater initial stability against overturning. The metacentric height also influences the natural period of rolling of a hull, with very large metacentric heights being associated with shorter periods of roll which are uncomfortable for passengers. Hence, a sufficiently, but not excessively, high metacentric height is considered ideal for passenger ships.

Sailing ships frequently encounter difficult conditions, whether by storm or combat, and the crew frequently called upon to cope with accidents, ranging from the parting of a single line to the whole destruction of the rigging, and from running aground to fire.

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water. Some remain current, while many date from the 17th to 19th centuries. The word nautical derives from the Latin nauticus, from Greek nautikos, from nautēs: "sailor", from naus: "ship".

Capsizing or keeling over occurs when a boat or ship is rolled on its side or further by wave action, instability or wind force beyond the angle of positive static stability or it is upside down in the water. The act of recovering a vessel from a capsize is called righting. Capsize may result from broaching, knockdown, loss of stability due to cargo shifting or flooding, or in high speed boats, from turning too fast.

In a keel boat, a death roll is the act of broaching to windward, putting the spinnaker pole into the water and causing a crash-jibe of the boom and mainsail, which sweep across the deck and plunge down into the water. The death roll often results in the destruction of the spinnaker pole and sometimes even the dismasting of the boat. Serious injury to crew is possible due to the swift and uncontrolled action of the boom and associated gear sweeping across the boat and crashing to the (now) leeward side.

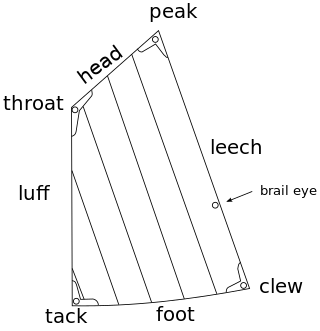

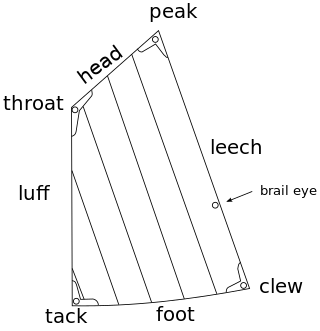

The spritsail is a four-sided, fore-and-aft sail that is supported at its highest points by the mast and a diagonally running spar known as the sprit. The foot of the sail can be stretched by a boom or held loose-footed just by its sheets. A spritsail has four corners: the throat, peak, clew, and tack. The Spritsail can also be used to describe a rig that uses a spritsail.

A boat is said to be turtling or to turn turtle when it is fully inverted. The name stems from the appearance of the upside-down boat, similar to the carapace of a sea turtle. The term can be applied to any vessel; turning turtle is less frequent but more dangerous on ships than on smaller boats. It is rarer but more hazardous for multihulls than for monohulls, because multihulls are harder to flip in both directions. Measures can be taken to prevent a capsize from becoming a turtle.

In sailing, heaving to is a way of slowing a sailing vessel's forward progress, as well as fixing the helm and sail positions so that the vessel does not have to be steered. It is commonly used for a "break"; this may be to wait for the tide before proceeding, or to wait out a strong or contrary wind. For a solo or shorthanded sailor it can provide time to go below deck, to attend to issues elsewhere on the boat or to take a meal break. Heaving to can make reefing a lot easier, especially in traditional vessels with several sails. It is also used as a storm tactic.

Self-steering gear is equipment used on sail boats to maintain a chosen course or point of sail without constant human action.

Weather helm is the tendency of sailing vessels to turn towards the source of wind, creating an unbalanced helm that requires pulling the tiller to windward in order to counteract the effect.

A sailing yacht, is a leisure craft that uses sails as its primary means of propulsion. A yacht may be a sail or power vessel used for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, so the term applies here to sailing vessels that have a cabin with amenities that accommodate overnight use. To be termed a "yacht", as opposed to a "boat", such a vessel is likely to be at least 33 feet (10 m) in length and have been judged to have good aesthetic qualities. Sailboats that do not accommodate overnight use or are smaller than 30 feet (9.1 m) are not universally called yachts. Sailing yachts in excess of 130 feet (40 m) are generally considered to be superyachts.

A sailing boat that is carrying too much sail for the current wind conditions is said to be over-canvassed. An over-canvassed boat, whether a dinghy, a yacht or a sailing ship, is difficult to steer and control and tends to heel or roll too much. If the wind continues to rise, an over-canvassed sailing boat will become dangerous and ultimately gear may break or it may round-up into the wind, broach or capsize. Any of these eventualities puts the safety of the crew and the vessel in danger. To over-canvass a sailing boat is considered unseamanlike and imprudent. In order to reduce sail, individual sails may be lowered or furled and existing sails may be reefed. Counter-intuitively, many boats will sail faster, and certainly more smoothly, comfortably and safely, when carrying the correct amount of sail in a strong wind than they would if over-canvassed and excessively rolling, heeling, carrying too much weather helm or repeatedly rounding up.

Forces on sails result from movement of air that interacts with sails and gives them motive power for sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and sail-powered land vehicles. Similar principles in a rotating frame of reference apply to windmill sails and wind turbine blades, which are also wind-driven. They are differentiated from forces on wings, and propeller blades, the actions of which are not adjusted to the wind. Kites also power certain sailing craft, but do not employ a mast to support the airfoil and are beyond the scope of this article.

Dismasting, also called demasting, occurs to a sailing ship when one or more of the masts responsible for hoisting the sails that propel the vessel breaks. Dismasting usually occurs as the result of high winds during a storm acting upon masts, sails, rigging, and spars.