Phoenician is an extinct Canaanite Semitic language originally spoken in the region surrounding the cities of Tyre and Sidon. Extensive Tyro-Sidonian trade and commercial dominance led to Phoenician becoming a lingua franca of the maritime Mediterranean during the Iron Age. The Phoenician alphabet spread to Greece during this period, where it became the source of all modern European scripts.

The Moabite language, also known as the Moabite dialect, is an extinct sub-language or dialect of the Canaanite languages, themselves a branch of Northwest Semitic languages, formerly spoken in the region described in the Bible as Moab in the early 1st millennium BC.

The Canaanite languages, sometimes referred to as Canaanite dialects, are one of three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, the others being Aramaic and Amorite. These closely related languages originate in the Levant and Mesopotamia, and were spoken by the ancient Semitic-speaking peoples of an area encompassing what is today, Israel, Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula, Lebanon, Syria, as well as some areas of southwestern Turkey (Anatolia), western and southern Iraq (Mesopotamia) and the northwestern corner of Saudi Arabia.

The Tel Dan Stele is a fragmentary stele containing an Aramaic inscription which dates to the 9th century BCE. It is notable for possibly being the most significant and perhaps the only extra-biblical archaeological reference to the house of David.

The Paleo-Hebrew script, also Palaeo-Hebrew, Proto-Hebrew or Old Hebrew, is the writing system found in Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, including pre-Biblical and Biblical Hebrew, from southern Canaan, also known as the biblical kingdoms of Israel (Samaria) and Judah. It is considered to be the script used to record the original texts of the Bible due to its similarity to the Samaritan script; the Talmud states that the Samaritans still used this script. The Talmud described it as the "Livonaʾa script", translated by some as "Lebanon script". However, it has also been suggested that the name is a corrupted form of "Neapolitan", i.e. of Nablus. Use of the term "Paleo-Hebrew alphabet" is due to a 1954 suggestion by Solomon Birnbaum, who argued that "[t]o apply the term Phoenician [from Northern Canaan, today's Lebanon] to the script of the Hebrews [from Southern Canaan, today's Israel-Palestine] is hardly suitable". The Paleo-Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets are two slight regional variants of the same script.

Zincirli Höyük is an archaeological site located in the Anti-Taurus Mountains of modern Turkey's Gaziantep Province. During its time under the control of the Neo-Assyrian Empire it was called, by them, Sam'al. It was founded at least as far back as the Early Bronze Age and thrived between 3000 and 2000 BC, and on the highest part of the upper mound was found a walled citadel of the Middle Bronze Age. New excavations revealed a monumental complex in the Middle Bronze Age II, and another structure that was destroyed in the mid to late 17th century BC, maybe by Hititte king Hattusili I. This event was recently radiocarbon-dated to sometime between 1632 and 1610 BC, during the late Middle Bronze Age II. The site was thought to have been abandoned during the Hittite and Mitanni periods, but excavations in 2021 season showed evidence of occupation during the Late Bronze Age in Hittite times. It flourished again in the Iron Age, initially under Luwian-speaking Neo-Hittites, and by 920 B.C. had become a kingdom. In the 9th and 8th century BC it came under control of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and by the 7th century BC had become a directly ruled Assyrian province.

Baalshamin, also called Baal Shamem and Baal Shamaim, was a Northwest Semitic god and a title applied to different gods at different places or times in ancient Middle Eastern inscriptions, especially in Canaan/Phoenicia and Syria. The title was most often applied to Hadad, who is also often titled just Ba‘al. Baalshamin was one of the two supreme gods and the sky god of pre-Islamic Palmyra in ancient Syria. There his attributes were the eagle and the lightning bolt, and he perhaps formed a triad with the lunar god Aglibol and the sun god Malakbel. The title was also applied to Zeus.

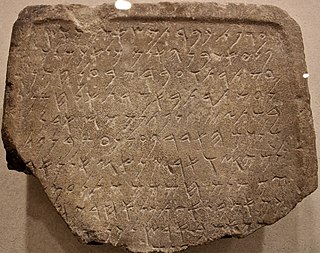

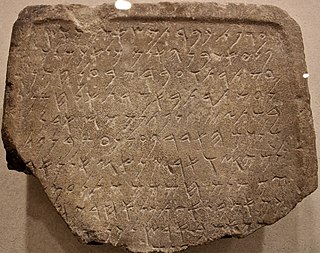

The Kilamuwa Stele is a 9th-century BC stele of King Kilamuwa, from the Kingdom of Bit-Gabbari. He claims to have succeeded where his ancestors had failed, in providing for his kingdom. The inscription is known as KAI 24.

Septimius Orodes was a Palmyrene official and a viceroy for king Odaenathus of Palmyra. He was given the surname Septimius by his monarch.

The Ma'sub inscription is a Phoenician-language inscription found at Khirbet Ma'sub near Al-Bassa. The inscription is from 222/21 BC. Written in Phoenician script, it is also known as KAI 19.

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the society and history of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may occur on stone slabs, pottery ostraca, ornaments, and range from simple names to full texts. The older inscriptions form a Canaanite–Aramaic dialect continuum, exemplified by writings which scholars have struggled to fit into either category, such as the Stele of Zakkur and the Deir Alla Inscription.

The Hadad Statue is an 8th-century BC stele of King Panamuwa I, from the Kingdom of Bit-Gabbari in Sam'al. It is currently occupies a prominent position in the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin.

The Bar-Rakib inscriptions are a group of 8th-century BC steles, or fragments of steles, of King Bar-Rakib, from Sam'al.

The Tamassos bilinguals are a pair of bilingual Cypriot–Phoenician inscriptions on stone pedestals found in 1885 in Tamassos, Cyprus. It has been dated to 363 BC.

The Cherchell Neopunic inscriptions are two Neopunic inscriptions on marble discovered in 1875 and 1882 in Cherchell in French Algeria. They are currently in the Louvre, known as AO 1028 and AO 5294.

The Bashamem inscription or Baalshamam inscription is a Phoenician language inscription found in Cagliari, Sardinia in 1877. It is currently in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari.

The Carthage Tariff is a Punic language inscription from the third century BCE, found on a fragments of a limestone stela in 1856-58 at Carthage in Tunisia. It is thought to be related to the Marseille Tariff, found two decades earlier.

The Pierides Kition inscriptions are seven Phoenician inscriptions found in Kition by Demetrios Pierides in 1881 and acquired by the Louvre in 1885.

The Carthage Festival inscription or Carthage Festival Offering inscription is an inscription from Carthage in the Punic language that probably describes the liturgy of a festival of, at least, five days. It is dated to the fourth or third century BCE.

Sakkun was a Phoenician god. He is known chiefly from theophoric names such as Sanchuniathon and Gisgo. As of 1940, his earliest appearance in epigraphical evidence is from the 5th century BC.