Cherokee spiritual beliefs are held in common among the Cherokee people – Native American peoples who are Indigenous to the Southeastern Woodlands, and today live primarily in communities in North Carolina, and Oklahoma. Some of the beliefs, and the stories and songs in which they have been preserved, exist in slightly different forms in the different communities in which they have been preserved. But for the most part, they still form a unified system of theology.

The Matagi are traditional winter hunters of the Tōhoku region of northern Japan, most famously today in the Ani area in Akita Prefecture, which is known for the Akita dogs. Afterwards, it spread to the Shirakami-Sanchi forest between Akita and Aomori, and other areas of Japan. Documented as a specialised group from the medieval period onwards, the Matagi continue to hunt deer and bear in the present day, and their culture has much in common with the bear worship of the Ainu people.

Finnish mythology is a commonly applied description of the folklore of Finnish paganism, of which a modern revival is practiced by a small percentage of the Finnish people. It has many features shared with Estonian and other Finnic mythologies, but also shares some similarities with neighbouring Baltic, Slavic and, to a lesser extent, Norse mythologies.

In Finnish mythology, Otso is a bear, the sacred king of animals and leader of the forest. It was deeply feared and respected by old Finnish tribes. Otso appears in the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala. Due to the importance of the bear spirit in historical Finnish paganism, bears are still considered by many Finns to be kings of the forest, and the bear is even the national animal of Finland.

Finnic paganism is the indigenous pagan religion in Finland, Karelia, Ingria and Estonia prior to Christianisation. It was a polytheistic religion, worshipping a number of different deities. The principal god was the god of thunder and the sky, Ukko; other important gods included Jumo (Jumala), Ahti, and Tapio. Jumala was a sky god; today, the word "Jumala" refers to all gods in general. Ahti was a god of the sea, waters and fish. Tapio was the god of forests and hunting.

Royal hunting, also royal art of hunting, was a hunting practice of the aristocracy throughout the known world in the Middle Ages, from Europe to Far East. While humans hunted wild animals since time immemorial, and all classes engaged in hunting as an important source of food and at times the principal source of nutrition. The necessity of hunting was transformed into a stylized pastime of the aristocracy. More than a pastime, it was an important arena for social interaction, essential training for war, and a privilege and measurement of nobility. In Europe in the High Middle Ages the practice was widespread.

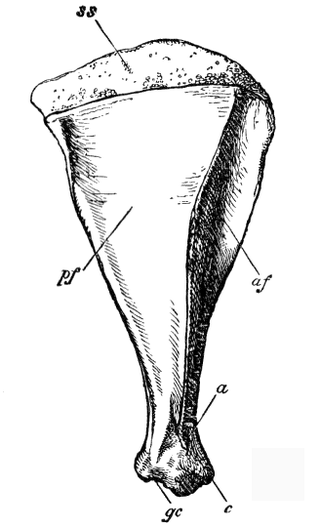

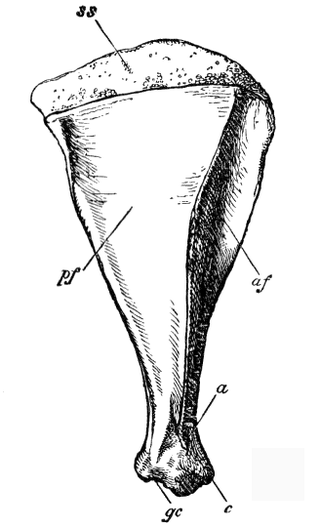

Scapulimancy is the practice of divination by use of scapulae or speal bones. It is most widely practiced in China and the Sinosphere as oracle bones, but has also been independently developed in the West.

Gawai Dayak is an annual festival and a public holiday celebrated by the Dayak people in Sarawak, Malaysia on 1 and 2 June. Sarawak Day is now celebrated on July 22 every year. Gawai Dayak was conceived of by the radio producers Tan Kingsley and Owen Liang and then taken up by the Dayak community. The British colonial government refused to recognise Dayak Day until 1962. They called it Sarawak Day for the inclusion of all Sarawakians as a national day, regardless of ethnic origin. It is both a religious and a social occasion recognised since 1957.

The Midewiwin or the Grand Medicine Society is a secretive religion of some of the Indigenous peoples of the Maritimes, New England and Great Lakes regions in North America. Its practitioners are called Midew, and the practices of Midewiwin are referred to as Mide. Occasionally, male Midew are called Midewinini, which is sometimes translated into English as "medicine man".

The Nemoralia is a three-day festival originally celebrated by the ancient Romans on the Ides of August in honor of the goddess Diana. Although the Nemoralia was originally celebrated at the Sanctuary of Diana at Lake Nemi, it soon became more widely celebrated. The Catholic Church may have adapted the Nemoralia as the Feast of the Assumption.

Bear worship is the religious practice of the worshipping of bears found in many North Eurasian ethnic religions such as among the Sami, Nivkh, Ainu, Basques, Germanic peoples, Slavs and Finns. There are also a number of deities from Celtic Gaul and Britain associated with the bear, and the Dacians, Thracians, and Getians were noted to worship bears and annually celebrate the bear dance festival. The bear is featured on many totems throughout northern cultures that carve them.

A kamuy is a spiritual or divine being in Ainu mythology, a term denoting a supernatural entity composed of or possessing spiritual energy.

Ultime grida dalla savana, also known as by its English title Savage Man Savage Beast, is a 1975 Italian mondo documentary film co-produced, co-written, co-edited and co-directed by Antonio Climati and Mario Morra. Filmed all around the world, its central theme focuses on hunting and the interaction between man and animal. Like many mondo films, the filmmakers claim to document real, bizarre and violent behavior and customs, although some scenes were actually staged. It is narrated by the Italian actor and popular dubber Giuseppe Rinaldi and the text was written by Italian novelist Alberto Moravia.

Bear hunting is the act of hunting bears. Bear have been hunted since prehistoric times for their meat and fur. In addition to being a source of food, in modern times they have been favored by big game hunters due to their size and ferocity. Bear hunting has a vast history throughout Europe and North America, and hunting practices have varied based on location and type of bear.

Lion hunting is the act of hunting lions. Lions have been hunted since antiquity.

The Astuvansalmi rock paintings are located in Ristiina, Mikkeli, Southern Savonia, Finland at the shores of the lake Yövesi, which is a part of the large lake Saimaa. The paintings are 7.7 to 11.8 metres above the water-level of lake Saimaa. The lake level was much higher at the time the rock paintings were made. There are about 70 paintings in the area.

Pialrâl is the ultimate heaven according to the folk myth of the Mizo tribes of Northeast India. The Mizo word literally means "beyond the world". Unlike most concepts of heaven, it is not the final resting place of the spirits of the good and the righteous, nor there is a role for god or any supernaturals, but is simply a reservation for extraordinary achievers during their lifetime to enjoy eternal bliss and luxury.

Karhun kansa (Finnish:['kɑrhunˈkɑnsɑ] is a religious community based on indigenous Finnish spiritual tradition. The community was officially recognized by the Finnish state in December 2013. "Karhun kansa" is Finnish for "People of the Bear". The bear, known as Otso, is the most sacred animal in the Finnish spiritual tradition, and said to be the mythical ancestor of all humankind. Karhun kansa is part of Suomenusko, the contemporary revival of pre-Christian polytheistic ethnic religion of the Finns. Some members of Karhun kansa call their faith 'väenusko' rather than 'suomenusko'. The first part of the term 'väenusko' stems from a Finnish word 'väki', which refers to people, and also both unseen and visible powers that are part of traditional Finnic mythology.

The Bladder Festival or Bladder Feast, is an important annual seal hunting harvest renewal ceremony and celebration held each year to honor and appease the souls of seals taken in the hunt during the past season which occurred at the winter solstice by the Yup'ik of western and southwestern Alaska.

The Kuru Dance and Music festival is an annual celebration included in the Botswana's calendar of events marking the full moon where Khoisan communities find it very significant in their culture to interchange cultural knowledge through song and dance.