Santa Rosa County is a county located in the northwestern portion of the U.S. state of Florida. As of 2020, the population was 188,000. The county seat is Milton, which lies in the geographic center of the county. Other major communities within Santa Rosa County are Navarre, Pace, and Gulf Breeze. Navarre is the most populated community with a population of approximately 45,000 residents. Santa Rosa County is included in the Pensacola—Ferry Pass—Brent, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area, which also includes Escambia County.

Destin is a city located in Okaloosa County, Florida, United States. It is a principal city of the Crestview–Fort Walton Beach–Destin, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 13,931 at the 2020 census, up from 12,305 at the 2010 census.

Pensacola Beach is an unincorporated community located on Santa Rosa Island, a barrier island, in Escambia County, Florida, United States. It is situated south of Pensacola in the Gulf of Mexico. As of the 2000 census, the community had a total population of 2,738. It has been described as "famous" for its ultra-white sand beaches.

Fort Pickens is a historic pentagonal United States military fort on Santa Rosa Island in the Pensacola, Florida, area. It is named after American Revolutionary War hero Andrew Pickens. It is the largest of four forts built to defend Pensacola Bay and its navy yard. The fort was completed in 1834 and was one of the few forts in the South that remained in Union hands throughout the American Civil War. It remained in use until 1947. Fort Pickens is included within the Gulf Islands National Seashore, and as such, is administered by the National Park Service.

Fort McRee was a historic military fort constructed by the United States on the eastern tip of Perdido Key to defend Pensacola and its important natural harbor. In the defense of Pensacola Bay, Fort McRee was accompanied by Fort Pickens, located across Pensacola Pass on Santa Rosa Island, and Fort Barrancas, located across Pensacola Bay on the grounds of what is now Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola. Fort Pickens was the largest of these. Very little remains of Fort McRee today.

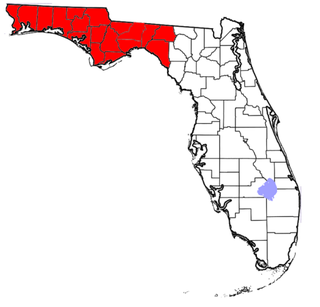

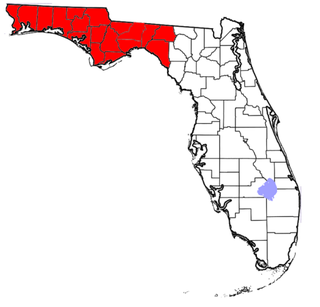

The Florida panhandle is the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Florida. It is a salient roughly 200 miles (320 km) long, bordered by Alabama on the north and the west, Georgia on the north, and the Gulf of Mexico to the south. Its eastern boundary is arbitrarily defined. It is defined by its southern culture and rural geography relative to the rest of Florida, as well as closer cultural links to French-influenced Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Its major communities include Pensacola, Navarre, Destin, Panama City Beach, and Tallahassee.

Santa Rosa Island is a 40-mile (64 km) barrier island located in the U.S. state of Florida, thirty miles (50 km) east of the Alabama state border. The communities of Pensacola Beach, Navarre Beach, and Okaloosa Island are located on the island. On the northern side of the island, are Pensacola Bay on the west and Choctawhatchee Bay on the east, joined through Santa Rosa Sound.

The Emerald Coast is an unofficial name for the coastal area in the US state of Florida on the Gulf of Mexico that stretches about 100 miles (160 km) through five counties, Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, Walton, and Bay, which include Pensacola Beach, Navarre Beach, Fort Walton Beach, Destin, and Panama City Beach. Some south Alabama communities on the coast of Baldwin County, such as Gulf Shores, Orange Beach, and Fort Morgan embrace the term as well.

Gulf Islands National Seashore is an American National seashore that offers recreation opportunities and preserves natural and historic resources along the Gulf of Mexico barrier islands of Florida and Mississippi. In 2023, it was the fifth-most visited unit of the National Park Service.

Fort Barrancas (1839) or Fort San Carlos de Barrancas is a United States military fort and National Historic Landmark in the former Warrington area of Pensacola, Florida, located physically within Naval Air Station Pensacola, which was developed later around it.

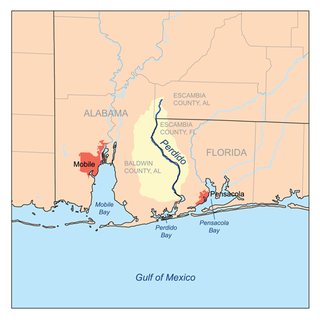

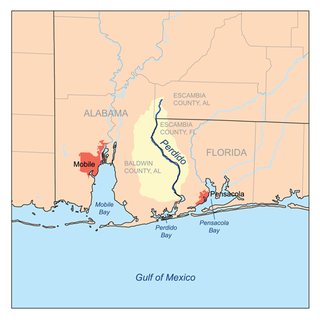

Perdido Key is an unincorporated community located in Escambia County, Florida, United States, between the cities of Pensacola, Florida and Orange Beach, Alabama. The community is located on and named for Perdido Key, a barrier island in northwest Florida and southeast Alabama. "Perdido" means "lost" in the Spanish and Portuguese languages. The Florida district of the Gulf Islands National Seashore includes the east end of the island, as well as other Florida islands. No more than a few hundred yards wide in most places, Perdido Key stretches some 16 miles (26 km) from near Pensacola to Perdido Pass Bridge near Orange Beach.

Tropical Storm Arlene was an unusually large and early-forming tropical storm, being the first of twenty-eight different storms during the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season, which would become the second most active season on record. Tropical Storm Arlene formed near Honduras on June 8 and moved northwards. It crossed western Cuba on June 10 and strengthened to just under hurricane strength before making its final landfall on the Florida Panhandle the next day. The storm weakened as it continued to move north over the United States, becoming extratropical on June 13. Arlene was responsible for two deaths and minor damage.

Pensacola Bay is a bay located in the northwestern part of Florida, United States, known as the Florida Panhandle.

Santa Rosa Sound is a sound connecting Pensacola Bay and Choctawhatchee Bay in Florida. The northern shore consists of the Fairpoint Peninsula and portions of the mainland in Santa Rosa County and Okaloosa County. It is bounded to the south by Santa Rosa Island, separating it from the Gulf of Mexico.

The Pensacola metropolitan area is the metropolitan area centered on Pensacola, Florida. It is also known as the Pensacola–Ferry Pass–Brent Metropolitan Statistical Area, a metropolitan statistical area (MSA) used for statistical purposes by the United States Census Bureau and other agencies. The Pensacola Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area was first defined in 1958, with Pensacola as the principal city, and included Escambia and Santa Rosa counties. The MSA was renamed Pensacola–Ferry Pass–Brent MSA in 2003, with the unincorporated census-designated places Ferry Pass and Brent added as principal cities. The population of the MSA in the 2020 census was 511,502.

The history of Pensacola, Florida, begins long before the Spanish claimed founding of the modern city in 1698. The area around present-day Pensacola was inhabited by Native American peoples thousands of years before the historical era.

Perdido Pass, separating Alabama Point from Florida Point, is the mouth of the Perdido River. Perdido Pass forms a water passage that connects Perdido Bay with the Gulf of Mexico to the south, in the U.S. state of Alabama, 2 miles (3 km) west of the Alabama/Florida state line. A bridge spans Perdido Pass, connecting Alabama Point with Florida Point in Alabama. At the entrance into the Gulf, the 2 rock barriers, extending from the white beaches, are the west jetty & east jetty. The surrounding area is heavily developed, with high-rise condominiums. However, there are nearby beach-front parks, with Gulf State Park on the eastern side of Perdido Pass.

Perdido Bay is a bay at the mouth of and draining the Perdido River, a designated Outstanding Florida Waters river, in Baldwin County, Alabama and Escambia County, Florida, United States. It is essentially a coastal lagoon enclosed by barrier islands, with an inlet, Perdido Pass.

The following is an alphabetical list of articles related to the U.S. state of Florida.

Perdido Key is a 24-kilometre-long (15 mi) barrier island on the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico. The island extends from Pensacola Pass on the east to Perdido Pass on the west. Most of the island is in Florida, with the western end of the island in Alabama. Santa Rosa Island is to the east of the island, and Alabama Point is to the west. Perdido Key was attached to the mainland until the 1940s when a canal separated it from the mainland. The eastern part of the island forms part of the Gulf Islands National Seashore, which includes the Perdido Key Historic District, the site of three shore batteries that once defended Pensacola Bay. The rest of the island, with the exception of the Perdido Key State Park, has been developed as a resort and residential community. As a barrier island, Perdidio Key is subject to changes due to wave action and longshore currents, particularly from hurricanes. The endangered Perdido Key beach mouse is endemic to the island.