The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution protects the right to keep and bear arms. It was ratified on December 15, 1791, along with nine other articles of the Bill of Rights. In District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), the Supreme Court affirmed for the first time that the right belongs to individuals, for self-defense in the home, while also including, as dicta, that the right is not unlimited and does not preclude the existence of certain long-standing prohibitions such as those forbidding "the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill" or restrictions on "the carrying of dangerous and unusual weapons". In McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010) the Supreme Court ruled that state and local governments are limited to the same extent as the federal government from infringing upon this right. New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen (2022) assured the right to carry weapons in public spaces with reasonable exceptions.

Gun laws in the United States regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition. State laws vary considerably, and are independent of existing federal firearms laws, although they are sometimes broader or more limited in scope than the federal laws.

Sidney Runyan Thomas is an American lawyer and jurist serving as a senior U.S. circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit since 1996. He served as the Ninth Circuit's chief judge from 2014 to 2021. His chambers are located in Billings, Montana.

In the United States, open carry refers to the practice of visibly carrying a firearm in public places, as distinguished from concealed carry, where firearms cannot be seen by the casual observer. To "carry" in this context indicates that the firearm is kept readily accessible on the person, within a holster or attached to a sling. Carrying a firearm directly in the hands, particularly in a firing position or combat stance, is known as "brandishing" and may constitute a serious crime, but is not the mode of "carrying" discussed in this article.

Diarmuid Fionntain O'Scannlain is a senior United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. His chambers are located in Portland, Oregon.

In the United States, the right to keep and bear arms is modulated by a variety of state and federal statutes. These laws generally regulate the manufacture, trade, possession, transfer, record keeping, transport, and destruction of firearms, ammunition, and firearms accessories. They are enforced by state, local and the federal agencies which include the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008), is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States. It ruled that the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects an individual's right to keep and bear arms—unconnected with service in a militia—for traditionally lawful purposes such as self-defense within the home, and that the District of Columbia's handgun ban and requirement that lawfully owned rifles and shotguns be kept "unloaded and disassembled or bound by a trigger lock" violated this guarantee. It also stated that the right to bear arms is not unlimited and that certain restrictions on guns and gun ownership were permissible. It was the first Supreme Court case to decide whether the Second Amendment protects an individual right to keep and bear arms for self-defense or whether the right was only intended for state militias.

Gun laws in California regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the state of California in the United States.

Roger Thomas Benitez is a senior United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of California. He is known for his rulings striking down several California gun control laws.

Nordyke v. King was a case in the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in which a ban of firearms on all public property and whether the Second Amendment should be applied to the state and local governments is to be decided. After several hearings at different levels of the federal court system, Alameda County, California promised that gun shows could be held on county property, essentially repudiating its ordinance.

McDonald v. City of Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that found that the right of an individual to "keep and bear arms", as protected under the Second Amendment, is incorporated by the Fourteenth Amendment and is thereby enforceable against the states. The decision cleared up the uncertainty left in the wake of District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) as to the scope of gun rights in regard to the states.

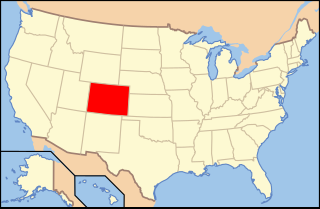

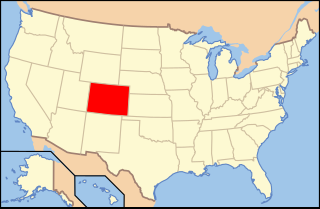

Gun laws in Colorado regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the state of Colorado in the United States.

Gun laws in the District of Columbia regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in Washington, D.C.

Gun laws in Hawaii regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the state of Hawaii, United States. Hawaii's gun laws are among the most restrictive in the country.

Gun laws in Maryland regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the U.S. state of Maryland.

Woollard v. Sheridan, 863 F. Supp. 2d 462, reversed sub. nom., Woollard v Gallagher, 712 F.3d 865, was a civil lawsuit brought on behalf of Raymond Woollard, a resident of the State of Maryland, by the Second Amendment Foundation against Terrence Sheridan, Secretary of the Maryland State Police, and members of the Maryland Handgun Permit Review Board. Plaintiffs allege that the Defendants' refusal to grant a concealed carry permit renewal to Mr. Woollard on the basis that he "...ha[d] not demonstrated a good and substantial reason to wear, carry or transport a handgun as a reasonable precaution against apprehended danger in the State of Maryland" was a violation of Mr. Woollard's rights under the Second and Fourteenth Amendments, and therefore unconstitutional. The trial court found in favor of Mr. Woollard, However, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the trial court and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review that decision.

Moore v. Madigan is the common name for a pair of cases decided in 2013 by the U.S. Court of Appeals, 7th Circuit, regarding the constitutionality of the State of Illinois' no-issue legislation and policy regarding the carry of concealed weapons. The plaintiffs, Michael Moore, Mary Shepard and the Second Amendment Foundation, sought an injunction against Illinois attorney general Lisa Madigan, Illinois Governor Patrick Quinn, and other named defendants, barring them from enforcing two key provisions of the Illinois Statutes prohibiting public possession of a firearm or other weapon.

People v. Aguilar, 2 N.E.3d 321, was an Illinois Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the Aggravated Unlawful Use of a Weapon (AUUF) statute violated the right to keep and bear arms as guaranteed by the Second Amendment. The Court stated that this was because the statute amounted to a wholesale statutory ban on the exercise of a personal right that was specifically named in and guaranteed by the United States Constitution, as construed by the United States Supreme Court. A conviction for Unlawful Possession of a Firearm (UPF) was proper because the possession of handguns by minors was conduct that fell outside the scope of the Second Amendment's protection.

New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, 597 U.S. 1 (2022), abbreviated NYSRPA v. Bruen and also known as NYSRPA II or Bruen to distinguish it from the 2020 case, is a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court related to the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution. The case concerned the constitutionality of the 1911 Sullivan Act, a New York State law requiring applicants for a pistol concealed carry license to show "proper cause", or a special need distinguishable from that of the general public, in their application.