Plant cells are eukaryotic cells present in green plants, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Their distinctive features include primary cell walls containing cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectin, the presence of plastids with the capability to perform photosynthesis and store starch, a large vacuole that regulates turgor pressure, the absence of flagella or centrioles, except in the gametes, and a unique method of cell division involving the formation of a cell plate or phragmoplast that separates the new daughter cells.

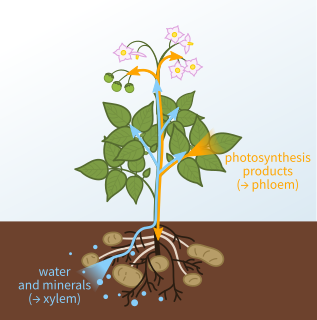

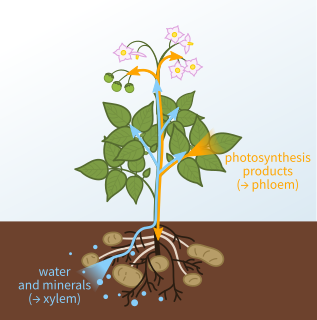

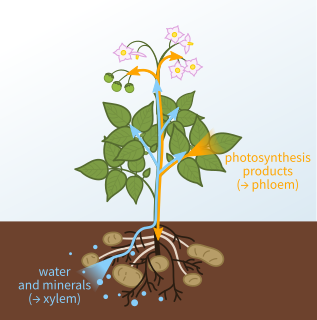

Xylem is one of the two types of transport tissue in vascular plants, the other being phloem. The basic function of xylem is to transport water from roots to stems and leaves, but it also transports nutrients. The word xylem is derived from the Ancient Greek word ξύλον (xylon), meaning "wood"; the best-known xylem tissue is wood, though it is found throughout a plant. The term was introduced by Carl Nägeli in 1858.

Phloem is the living tissue in vascular plants that transports the soluble organic compounds made during photosynthesis and known as photosynthates, in particular the sugar sucrose, to the rest of the plant. This transport process is called translocation. In trees, the phloem is the innermost layer of the bark, hence the name, derived from the Ancient Greek word φλοιός (phloiós), meaning "bark". The term was introduced by Carl Nägeli in 1858.

Vascular plants, also called tracheophytes or collectively Tracheophyta, form a large group of land plants that have lignified tissues for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They also have a specialized non-lignified tissue to conduct products of photosynthesis. Vascular plants include the clubmosses, horsetails, ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. Scientific names for the group include Tracheophyta, Tracheobionta and Equisetopsida sensu lato. Some early land plants had less developed vascular tissue; the term eutracheophyte has been used for all other vascular plants, including all living ones.

Root pressure is the transverse osmotic pressure within the cells of a root system that causes sap to rise through a plant stem to the leaves.

The vascular cambium is the main growth tissue in the stems and roots of many plants, specifically in dicots such as buttercups and oak trees, gymnosperms such as pine trees, as well as in certain other vascular plants. It produces secondary xylem inwards, towards the pith, and secondary phloem outwards, towards the bark.

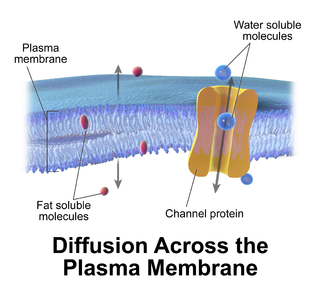

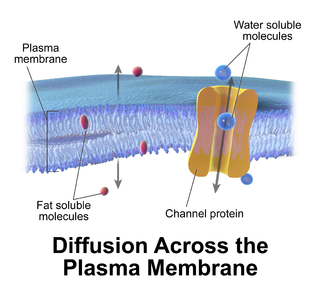

Passive transport is a type of membrane transport that does not require energy to move substances across cell membranes. Instead of using cellular energy, like active transport, passive transport relies on the second law of thermodynamics to drive the movement of substances across cell membranes. Fundamentally, substances follow Fick's first law, and move from an area of high concentration to one of low concentration because this movement increases the entropy of the overall system. The rate of passive transport depends on the permeability of the cell membrane, which, in turn, depends on the organization and characteristics of the membrane lipids and proteins. The four main kinds of passive transport are simple diffusion, facilitated diffusion, filtration, and/or osmosis.

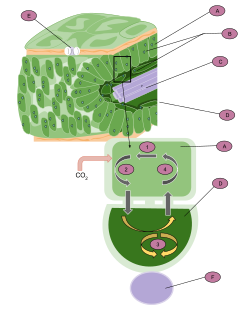

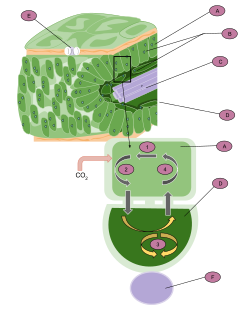

C4 carbon fixation or the Hatch–Slack pathway is one of three known photosynthetic processes of carbon fixation in plants. It owes the names to the 1960's discovery by Marshall Davidson Hatch and Charles Roger Slack that some plants, when supplied with 14CO2, incorporate the 14C label into four-carbon molecules first.

An autoradiograph is an image on an X-ray film or nuclear emulsion produced by the pattern of decay emissions from a distribution of a radioactive substance. Alternatively, the autoradiograph is also available as a digital image, due to the recent development of scintillation gas detectors or rare earth phosphorimaging systems. The film or emulsion is apposed to the labeled tissue section to obtain the autoradiograph. The auto- prefix indicates that the radioactive substance is within the sample, as distinguished from the case of historadiography or microradiography, in which the sample is marked using an external source. Some autoradiographs can be examined microscopically for localization of silver grains in which the process is termed micro-autoradiography. For example, micro-autoradiography was used to examine whether atrazine was being metabolized by the hornwort plant or by epiphytic microorganisms in the biofilm layer surrounding the plant.

Sap is a fluid transported in xylem cells or phloem sieve tube elements of a plant. These cells transport water and nutrients throughout the plant.

Inside a plant, the apoplast can mean the space outside of cell membranes, where material can diffuse freely; that is, the extracellular spaces. Apoplast can also refer especially to the continuum of cell walls of adjacent cells; fluid and material flows occurring there or in any extacellular space are called apoplastic flow or apoplastic transport.

The symplast of a plant is the inner side of a cell membrane in which water and low-molecular-weight solutes can freely diffuse. Symplast cells have more than one nucleus.

Plasmodesmata are microscopic channels which traverse the cell walls of plant cells and some algal cells, enabling transport and communication between them. Plasmodesmata evolved independently in several lineages, and species that have these structures include members of the Charophyceae, Charales, Coleochaetales and Phaeophyceae, as well as all embryophytes, better known as land plants. Unlike animal cells, almost every plant cell is surrounded by a polysaccharide cell wall. Neighbouring plant cells are therefore separated by a pair of cell walls and the intervening middle lamella, forming an extracellular domain known as the apoplast. Although cell walls are permeable to small soluble proteins and other solutes, plasmodesmata enable direct, regulated, symplastic transport of substances between cells. There are two forms of plasmodesmata: primary plasmodesmata, which are formed during cell division, and secondary plasmodesmata, which can form between mature cells.

Sieve elements are specialized cells that are important for the function of phloem, which is a highly organized tissue that transports organic compounds made during photosynthesis. Sieve elements are the major conducting cells in phloem. Conducting cells aid in transport of molecules especially for long-distance signaling. In plant anatomy, there are two main types of sieve elements. Companion cells and sieve cells originate from meristems, which are tissues that actively divide throughout a plant's lifetime. They are similar to the development of xylem, a water conducting tissue in plants whose main function is also transportation in the plant vascular system. Sieve elements' major function includes transporting sugars over long distance through plants by acting as a channel. Sieve elements elongate cells containing sieve areas on their walls. Pores on sieve areas allow for cytoplasmic connections to neighboring cells, which allows for the movement of photosynthetic material and other organic molecules necessary for tissue function. Structurally, they are elongated and parallel to the organ or tissue that they are located in. Sieve elements typically lack a nucleus and contain none to a very small number of ribosomes. The two types of sieve elements, sieve tube members and sieve cells, have different structures. Sieve tube members are shorter and wider with greater area for nutrient transport while sieve cells tend to be longer and narrower with smaller area for nutrient transport. Although the function of both of these kinds of sieve elements is the same, sieve cells are found in gymnosperms, non-flowering vascular plants, while sieve tube members are found in angiosperms, flowering vascular plants.

The ascent of sap in the xylem tissue of plants is the upward movement of water and minerals from the root to the aerial parts of the plant. The conducting cells in xylem are typically non-living and include, in various groups of plants, vessel members and tracheids. Both of these cell types have thick, lignified secondary cell walls and are dead at maturity. Although several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how sap moves through the xylem, the cohesion-tension mechanism has the most support. Although cohesion-tension has received criticism due to the apparent existence of large negative pressures in some living plants, experimental and observational data favor this mechanism.

The pressure flow hypothesis, also known as the mass flow hypothesis, is the best-supported theory to explain the movement of sap through the phloem. It was proposed by Ernst Münch, a German plant physiologist in 1930. A high concentration of organic substances, particularly sugar, inside cells of the phloem at a source, such as a leaf, creates a diffusion gradient that draws water into the cells from the adjacent xylem. This creates turgor pressure, also known as hydrostatic pressure, in the phloem. Movement of phloem sap occurs by bulk flow from sugar sources to sugar sinks. The movement in phloem is bidirectional, whereas, in xylem cells, it is unidirectional (upward). Because of this multi-directional flow, coupled with the fact that sap cannot move with ease between adjacent sieve-tubes, it is not unusual for sap in adjacent sieve-tubes to be flowing in opposite directions.

The exodermis is a physiological barrier that has a role in root function and protection. The exodermis is a membrane of variable permeability responsible for the radial flow of water, ions, and nutrients. It is the outer layer of a plant's cortex. The exodermis serves a double function as it can protect the root from invasion by foreign pathogens and ensures that the plant does not lose too much water through diffusion through the root system and can properly replenish its stores at an appropriate rate.

Leaf expansion is a process by which plants make efficient use of the space around them by causing their leaves to enlarge, or wither. This process enables a plant to maximize its own biomass, whether it be due to increased surface area; which enables more sunlight to be absorbed by chloroplasts, driving the rate of photosynthesis upward, or it enables more stomata to be created on the leaf surface, allowing the plant to increase its carbon dioxide intake.

The P-type plasma membrane H+

-ATPase is found in plants and fungi. For the gastric H+

/K+

ATPase, see Hydrogen potassium ATPase.

Plant root exudates are fluids emitted through the roots of plants. These secretion influence the rhizosphere around the roots to inhibit harmful microbes and promote the grow of self and kin plants.