Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, than the absorbed radiation. A perceptible example of fluorescence occurs when the absorbed radiation is in the ultraviolet region of the electromagnetic spectrum, while the emitted light is in the visible region; this gives the fluorescent substance a distinct color that can only be seen when the substance has been exposed to UV light. Fluorescent materials cease to glow nearly immediately when the radiation source stops, unlike phosphorescent materials, which continue to emit light for some time after.

In science, specifically statistical mechanics, a population inversion occurs while a system exists in a state in which more members of the system are in higher, excited states than in lower, unexcited energy states. It is called an "inversion" because in many familiar and commonly encountered physical systems, this is not possible. This concept is of fundamental importance in laser science because the production of a population inversion is a necessary step in the workings of a standard laser.

Spontaneous emission is the process in which a quantum mechanical system transits from an excited energy state to a lower energy state and emits a quantized amount of energy in the form of a photon. Spontaneous emission is ultimately responsible for most of the light we see all around us; it is so ubiquitous that there are many names given to what is essentially the same process. If atoms are excited by some means other than heating, the spontaneous emission is called luminescence. For example, fireflies are luminescent. And there are different forms of luminescence depending on how excited atoms are produced. If the excitation is affected by the absorption of radiation the spontaneous emission is called fluorescence. Sometimes molecules have a metastable level and continue to fluoresce long after the exciting radiation is turned off; this is called phosphorescence. Figurines that glow in the dark are phosphorescent. Lasers start via spontaneous emission, then during continuous operation work by stimulated emission.

Luminescence is spontaneous emission of light by a substance not resulting from heat; or "cold light".

Photoluminescence is light emission from any form of matter after the absorption of photons. It is one of many forms of luminescence and is initiated by photoexcitation, hence the prefix photo-. Following excitation, various relaxation processes typically occur in which other photons are re-radiated. Time periods between absorption and emission may vary: ranging from short femtosecond-regime for emission involving free-carrier plasma in inorganic semiconductors up to milliseconds for phosphoresence processes in molecular systems; and under special circumstances delay of emission may even span to minutes or hours.

Cathodoluminescence is an optical and electromagnetic phenomenon in which electrons impacting on a luminescent material such as a phosphor, cause the emission of photons which may have wavelengths in the visible spectrum. A familiar example is the generation of light by an electron beam scanning the phosphor-coated inner surface of the screen of a television that uses a cathode ray tube. Cathodoluminescence is the inverse of the photoelectric effect, in which electron emission is induced by irradiation with photons.

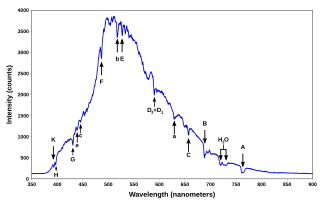

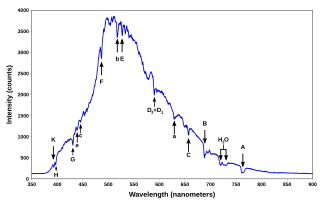

A spectral line is a dark or bright line in an otherwise uniform and continuous spectrum, resulting from emission or absorption of light in a narrow frequency range, compared with the nearby frequencies. Spectral lines are often used to identify atoms and molecules. These "fingerprints" can be compared to the previously collected ones of atoms and molecules, and are thus used to identify the atomic and molecular components of stars and planets, which would otherwise be impossible.

The emission spectrum of a chemical element or chemical compound is the spectrum of frequencies of electromagnetic radiation emitted due to an electron making a transition from a high energy state to a lower energy state. The photon energy of the emitted photon is equal to the energy difference between the two states. There are many possible electron transitions for each atom, and each transition has a specific energy difference. This collection of different transitions, leading to different radiated wavelengths, make up an emission spectrum. Each element's emission spectrum is unique. Therefore, spectroscopy can be used to identify elements in matter of unknown composition. Similarly, the emission spectra of molecules can be used in chemical analysis of substances.

Phosphorescence is a type of photoluminescence related to fluorescence. When exposed to light (radiation) of a shorter wavelength, a phosphorescent substance will glow, absorbing the light and reemitting it at a longer wavelength. Unlike fluorescence, a phosphorescent material does not immediately reemit the radiation it absorbs. Instead, a phosphorescent material absorbs some of the radiation energy and reemits it for a much longer time after the radiation source is removed.

Fluorescence spectroscopy is a type of electromagnetic spectroscopy that analyzes fluorescence from a sample. It involves using a beam of light, usually ultraviolet light, that excites the electrons in molecules of certain compounds and causes them to emit light; typically, but not necessarily, visible light. A complementary technique is absorption spectroscopy. In the special case of single molecule fluorescence spectroscopy, intensity fluctuations from the emitted light are measured from either single fluorophores, or pairs of fluorophores.

Electron excitation is the transfer of a bound electron to a more energetic, but still bound state. This can be done by photoexcitation (PE), where the electron absorbs a photon and gains all its energy or by electrical excitation (EE), where the electron receives energy from another, energetic electron. Within a semiconductor crystal lattice, thermal excitation is a process where lattice vibrations provide enough energy to transfer electrons to a higher energy band such as a more energetic sublevel or energy level. When an excited electron falls back to a state of lower energy, it undergoes electron relaxation(deexcitation). This is accompanied by the emission of a photon or by a transfer of energy to another particle. The energy released is equal to the difference in energy levels between the electron energy states.

In physics and physical chemistry, time-resolved spectroscopy is the study of dynamic processes in materials or chemical compounds by means of spectroscopic techniques. Most often, processes are studied after the illumination of a material occurs, but in principle, the technique can be applied to any process that leads to a change in properties of a material. With the help of pulsed lasers, it is possible to study processes that occur on time scales as short as 10−16 seconds. All time-resolved spectra are suitable to be analyzed using the two-dimensional correlation method for a correlation map between the peaks.

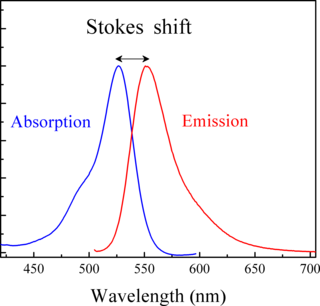

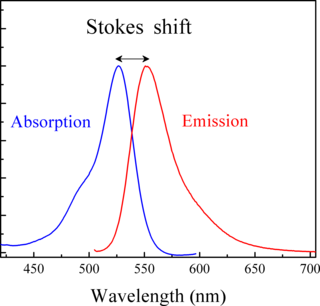

Stokes shift is the difference between positions of the band maxima of the absorption and emission spectra of the same electronic transition. It is named after Irish physicist George Gabriel Stokes. Sometimes Stokes shifts are given in wavelength units, but this is less meaningful than energy, wavenumber or frequency units because it depends on the absorption wavelength. For instance, a 50 nm Stokes shift from absorption at 300 nm is larger in terms of energy than a 50 nm Stokes shift from absorption at 600 nm.

Resonance Raman spectroscopy is a Raman spectroscopy technique in which the incident photon energy is close in energy to an electronic transition of a compound or material under examination. The frequency coincidence can lead to greatly enhanced intensity of the Raman scattering, which facilitates the study of chemical compounds present at low concentrations.

Ultrafast laser spectroscopy is a spectroscopic technique that uses ultrashort pulse lasers for the study of dynamics on extremely short time scales. Different methods are used to examine the dynamics of charge carriers, atoms, and molecules. Many different procedures have been developed spanning different time scales and photon energy ranges; some common methods are listed below.

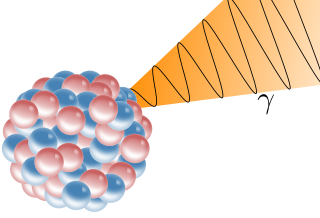

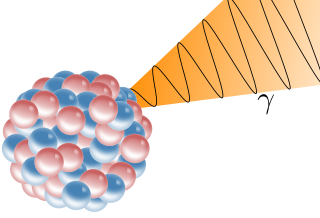

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or ), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically shorter than those of X-rays. With frequencies above 30 exahertz (30×1018 Hz), it imparts the highest photon energy. Paul Villard, a French chemist and physicist, discovered gamma radiation in 1900 while studying radiation emitted by radium. In 1903, Ernest Rutherford named this radiation gamma rays based on their relatively strong penetration of matter; in 1900 he had already named two less penetrating types of decay radiation (discovered by Henri Becquerel) alpha rays and beta rays in ascending order of penetrating power.

Photoelectrochemical processes are processes in photoelectrochemistry; they usually involve transforming light into other forms of energy. These processes apply to photochemistry, optically pumped lasers, sensitized solar cells, luminescence, and photochromism.

The semiconductor luminescence equations (SLEs) describe luminescence of semiconductors resulting from spontaneous recombination of electronic excitations, producing a flux of spontaneously emitted light. This description established the first step toward semiconductor quantum optics because the SLEs simultaneously includes the quantized light–matter interaction and the Coulomb-interaction coupling among electronic excitations within a semiconductor. The SLEs are one of the most accurate methods to describe light emission in semiconductors and they are suited for a systematic modeling of semiconductor emission ranging from excitonic luminescence to lasers.

The Elliott formula describes analytically, or with few adjustable parameters such as the dephasing constant, the light absorption or emission spectra of solids. It was originally derived by Roger James Elliott to describe linear absorption based on properties of a single electron–hole pair. The analysis can be extended to a many-body investigation with full predictive powers when all parameters are computed microscopically using, e.g., the semiconductor Bloch equations or the semiconductor luminescence equations.

Upconverting nanoparticles (UCNPs) are nanoscale particles that exhibit photon upconversion. In photon upconversion, two or more incident photons of relatively low energy are absorbed and converted into one emitted photon with higher energy. Generally, absorption occurs in the infrared, while emission occurs in the visible or ultraviolet regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. UCNPs are usually composed of rare-earth based lanthanide- or actinide-doped transition metals and are of particular interest for their applications in in vivo bio-imaging, bio-sensing, and nanomedicine because of their highly efficient cellular uptake and high optical penetrating power with little background noise in the deep tissue level. They also have potential applications in photovoltaics and security, such as infrared detection of hazardous materials.