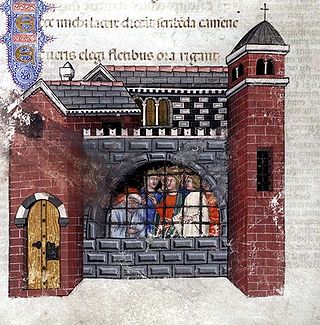

Pierce the Ploughman's Crede is a medieval alliterative poem of 855 lines, lampooning the four orders of friars.

Pierce the Ploughman's Crede is a medieval alliterative poem of 855 lines, lampooning the four orders of friars.

Surviving in two complete 16th-century manuscripts and two early printed editions, [1] the Crede can be dated on internal evidence to the short period between 1393 and 1400. The text in British Library MS Royal 18.B.17 appears before a C-text version of Piers Plowman in the same hand; that in Trinity College Cambridge MS R.3.15 is by a clerk in Archbishop Matthew Parker's household, who added Chaucer-related materials before a deficient 15th-century Canterbury Tales manuscript, and the Crede at the end of the manuscript. Additionally, BL MS Harley 78 contains a fragment of the Crede copied c. 1460–70. [2]

The Crede was first printed in London by Reyner Wolfe, [3] and then reprinted for inclusion with Owen Rogers's 1561 reprint of Robert Crowley's 1550 edition of Piers Plowman. [4] The Crede was not printed again until Thomas Bensley's edition in 1814, based on that of 1553, and Thomas Wright's of 1832. [5] The 1553 and 1561 editions were altered to include more anticlericalism and to attack an "abbot" where the original text had "bishop". This latter revision is a conservative one, undoubtedly motivated by the security of attacking a defunct institution following the dissolution of the monasteries rather than an aspect of Catholicism which survived in the Church of England. Nearly all modern critics have agreed that several lines about transubstantiation were removed. This excision was covered with a (perhaps interpolated) passage not found in any of the manuscripts.

The poem exists in several modern editions: Thomas Wright and Walter Skeat produced independent versions in the 19th century; more recently, James Dean has edited the text for TEAMs, and Helen Barr has produced an annotated edition in The Piers Plowman Tradition (London: J.M. Dent, 1993) ( ISBN 0-460-87050-5).

Some scholars believe it is very likely that the author of the Crede may also be responsible for the anti-fraternal Plowman's Tale , also known as the Complaint of the Ploughman. Both texts were probably composed at about the same time, with The Plowman's Tale being later and drawing extensively on the Crede. The author/speaker of The Plowman's Tale mentions that he will not deal with friars, since he has already dealt with them "before, / In a making of a 'Crede'..." W. W. Skeat believed that The Plowman's Tale and the Crede were definitely by the same person, although they differ in style. Others reject this thesis, suggesting that the author of The Plowman's Tale makes the extra-textual reference to a creed to enhance his own authority.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Crede was usually attributed to Chaucer. The editor of the 1606 edition of The Plowman's Tale, possibly Anthony Wotton, explains his speculations with this gloss: "A Creede: Some think hee means the questions of Jack-vpland, or perhaps Pierce Ploughmans Creede. For Chaucer speaks this in the person of the Pelican, not in his own person." This statement is ambivalent, suggesting that Chaucer could fictionally ("in the person of the Pelican") claim authorship for another text that he may not have actually written (i.e., the Crede), or Chaucer might be referring to one of his own writings (i.e., Jack Upland). Since Jack Upland was definitely (and wrongly) attributed to Chaucer in the 16th century, the editor is likely introducing the possibility of a fictive authorship claim to deal with the possibility that The Plowman's Tale refers to the Crede. In this way the editor may have thought that if Jack Upland is signified by the "crede" reference in The Plowman's Tale, then "Chaucer" is speaking; if the Crede is signified, then it is the "Pelican, not [Chaucer's] own person."

The Crede might also have been attributed to "Robert Langland" (i.e., William Langland) because of its inclusion in the 1561 edition of Piers Plowman, although this edition dropped the preface by Robert Crowley that names Langland. One reader of the 1561 Piers Plowman (which appends the Crede) made notes (dated 1577) in his copy that quote John Bale's attribution of Piers Plowman to Langland ("ex primis J. Wiclevi discipulis Unum") in Bale's Index...Scriptorum. Because of differences in language and his belief that Chaucer lived later than Langland, the reader concludes that the Crede alone (and not Piers Plowman) is Chaucer's.

Like much political or religious poetry of the Alliterative Revival (i.e., Piers Plowman , Mum and the Sothsegger ), the poem takes the form of a quest for knowledge. It is narrated by a layman who has memorized nearly all of the rudimentary texts demanded by the Fourth Lateran Council. He can read, and can recite the Ave Maria and Pater Noster proficiently: yet he does not know the Creed. He seeks help from the friars, first turning to the Franciscans, then the Dominicans, followed by the Austin friars and the Carmelites. But rather than learning anything of value, all he hears are imprecations. Each order savagely attacks one of its rival groups of mendicants: the Franciscans denounce the Carmelites; the Carmelites denounce the Dominicans; the Dominicans denounce the Augustines; the Augustines complete this carousel of invective by denouncing the Franciscans. The entire poem seems like an uproarious inversion of cantos xi and xii of Dante's Paradiso: just as Dante has the Dominican Aquinas and the Franciscan Bonaventure lauding one another's orders, so the Crede-poet makes the mendicants exchange abuse.

But all is not entirely lost. As he returns home, the narrator encounters a poor Plowman, dressed in rags and so emaciated that men myyte reken ich a ryb (432). Although starving, the Plowman freely offers the narrator what food he does have. When the narrator tells him of his experiences with the friars, the Plowman launches into a blistering diatribe on the four orders. Recognizing the wisdom of the Plowman's words, the narrator asks him whether he can teach him the Creed. He is glad to do so: the poem ends with the Plowman's recital of the elusive text.

Two features make the Crede particularly worthy of note. Firstly, it is the earliest text to imitate William Langland's Piers Plowman , to which it refers explicitly. The selfless Plowman is of course directly drawn from the earlier work. Perhaps written within eight years of the C-text of Piers Plowman, the Crede thus testifies to the appeal of Langland's more subversive, anticlerical sentiments among some of his early readers. Of course, the Crede-poet only uses Piers Plowman as a launch-pad for his own views. The Crede is markedly more confident than Langland in its opposition to the clergy. The fact that it abandons Langland's dream-vision framework is suggestive of this as if the lay perfection that the Plowman represents has become more achievable in reality. The Crede conflates Piers (here, "Peres") with the author/dreamer of Piers Plowman, thus collapsing that poem's many voices into a single, collective voice of the ideal community. This misprision was a common aspect of Piers Plowman's dissemination. The character of Piers thus escapes from the confines of William Langland's vision and takes on a life, an authority, and an authorial career of his own. As in The Plowman's Tale and The Prayer and Complaint of the Plowman, true religion is the virtue of the poor. The Piers of the Crede is simply a plowman without the Christological aspect of Piers in Langland's poem.

A second, related point of interest is that the Crede is a Lollard production that acknowledges the influence of Walter Map's Latin, anti-monastic "Goliardic" satires, such as "The Apocalypse of Bishop Golias" and "The Confession of Golias." The author of the Crede claims that these works tarnished the monastic orders and brought on the mendicant orders, or else Satan himself founded them. With clear Lollard sympathies, the Crede praises John Wycliffe and as well as Walter Brut who is mentioned concerning his heresy trial. (There were several trials for Brut, a Welsh Lollard, from 1391 to 1393.)

The Crede's content wholly conforms to Lollard views of the friars. Most of the charges against the friars are familiar from other works such as Jack Upland , the Vae Octuplex or Wyclif's Trialogus, and most are ultimately derived from William of Saint-Amour's De Periculis Novissimorum Temporum (1256). As in all Wycliffite satire, the friars are lecherous, covetous, greedy, vengeful, demanding extravagant donations for even the most elementary services. They seek out only the fattest corpses to bury and live in ostentatious houses that are more like palaces than places of worship. They are the children of Lucifer rather than Saint Dominic or St Francis, and follow in the footsteps of Cain, the first treacherous frater. But the fact that the poem's main approach is dramatic rather than didactic or polemic, and its frequent passages of striking physical description, elevate it beyond the vast bulk of antifraternal writing. Elizabeth Salter's charge of empty 'sensationalism' seems highly unjust. [ according to whom? ] The poem's vicious and unremitting attacks are impressively constructed, and even entertaining in their lacerating cynicism. Plus, as von Nolcken and Barr have shown, there is a remarkable subtlety to the poem, as it draws on even the most purely philosophical aspects of Wyclif's system. The opposition between the friars and Piers is finely crafted. While the friars squabble and bicker with one another, the true (i.e., Lollard) Christians form a single unity; at the end of the poem, in the words of Barr, 'the voices of Peres, narrator and poet all merge' into a single 'I':

|

Geoffrey Chaucer was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for The Canterbury Tales. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He was the first writer to be buried in what has since come to be called Poets' Corner, in Westminster Abbey. Chaucer also gained fame as a philosopher and astronomer, composing the scientific A Treatise on the Astrolabe for his 10-year-old son, Lewis. He maintained a career in the civil service as a bureaucrat, courtier, diplomat, and member of parliament.

Piers Plowman or Visio Willelmi de Petro Ploughman is a Middle English allegorical narrative poem by William Langland. It is written in un-rhymed, alliterative verse divided into sections called passus.

William Langland is the presumed author of a work of Middle English alliterative verse generally known as Piers Plowman, an allegory with a complex variety of religious themes. The poem translated the language and concepts of the cloister into symbols and images that could be understood by a layman.

The Hengwrt Chaucer manuscript is an early-15th-century manuscript of the Canterbury Tales, held in the National Library of Wales, in Aberystwyth. It is an important source for Chaucer's text, and was possibly written by someone with access to an original authorial holograph, now lost.

Walter William Skeat, was a British philologist and Anglican deacon. The pre-eminent British philologist of his time, he was instrumental in developing the English language as a higher education subject in the United Kingdom.

The Simonie, also known as Symonie and Couetise, is a Middle English poem on the evil times of the reign of King Edward II.

A dream vision or visio is a literary device in which a dream or vision is recounted as having revealed knowledge or a truth that is not available to the dreamer or visionary in a normal waking state. While dreams occur frequently throughout the history of literature, visionary literature as a genre began to flourish suddenly, and is especially characteristic in early medieval Europe. In both its ancient and medieval form, the dream vision is often felt to be of divine origin. The genre reemerged in the era of Romanticism, when dreams were regarded as creative gateways to imaginative possibilities beyond rational calculation.

There are two pseudo-Chaucerian texts called "The Plowman's Tale".

Jack Upland or Jack up Lande is a polemical, probably Lollard, literary work which can be seen as a "sequel" to Piers Plowman, with Antichrist attacking Christians through corrupt confession. Jack asks a "flattering friar" nearly seventy questions attacking the mendicant orders and exposing their distance from scriptural truth.

The Piers Plowman tradition is made up of about 14 different poetic and prose works from about the time of John Ball and the Peasants Revolt of 1381 through the reign of Elizabeth I and beyond. All the works feature one or more characters, typically Piers, from William Langland's poem Piers Plowman. Because the Plowman appears in the General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer but does not have his own tale, plowman tales are sometimes used as additions to The Canterbury Tales, or otherwise conflated or associated with Chaucer.

The Praier and Complaynte of the Ploweman unto Christe: written not longe after the yere of our Lorde. M. and three hundred is a short, anonymous English Christian text, probably written in the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century and first printed in about 1531. It consists of a prose tract, in the form of a polemical prayer, expressing Lollard sentiments and arguing for religious reform. In it, the simple ploughman/narrator speaks on behalf of "the repressed common man imbued with the simple truths of the Bible and a knowledge of the commandments against the mighty and monolithic conservative church". The pastoral-ecclesiastical metaphor of shepherds and sheep is used extensively as a number of criticisms are made about such things as confession, indulgences, purgatory, tithing and celibacy. The Prayer became important in the sixteenth century, when its themes were taken up by proponents of the Protestant Reformation.

Mum and the Sothsegger is an anonymous fifteenth century alliterative English poem, written during the "Alliterative Revival." It is ostensibly an example of medieval debate poetry between the principles of the oppressive figure of Mum and the unruly, wild Sothsegger.

Richard the Redeless is an anonymous fifteenth-century English alliterative poem that critiques Richard II's kingship and his court, seeking to offer Richard retrospective advice, following his deposition by Henry IV in 1399. The poet claims that "Richard has been poorly advised, his kingdom mismanaged, his loyal subjects ill-served." The author believes that the advice he imparts will be of great aid to any guiding the kingdom in future years. The poem also contains elements of satire, especially towards court manners and clothing fashions.

Wynnere and Wastoure is a fragmentary Middle English poem written in alliterative verse around the middle of the 14th century.

The Alliterative Revival is a term adopted by literary historians to refer to the resurgence of poetry using the alliterative verse form in Middle English between c. 1350 and 1500. Alliterative verse was the traditional verse form of Old English poetry; the last known alliterative poem prior to the Revival was Layamon's Brut, which dates from around 1190.

Anne Middleton was an American medievalist, and the Florence Green Bixby Professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley.

Helen Barr is an academic specialising in English literature on the late medieval period. She has spent her entire career at the University of Oxford, and, in 2016, the university awarded her the title of Professor of English Literature.

Thorlac Francis Samuel Turville-Petre is an English philologist who is Professor Emeritus and former head of the School of English at the University of Nottingham. He specializes in the study of Middle English literature.

"Y Llafurwr", known in English as "The Ploughman" or "The Labourer", is a poem in the form of a cywydd by the 14th-century Welsh poet Iolo Goch. Often compared with William Langland's Middle English Piers Plowman, it presents a sympathetic portrayal of the meek and godly ploughman; no other Welsh bardic poem takes an ordinary working man as its subject. It has been called the most notable of Iolo's poems, comparable with the finest works of Dafydd ap Gwilym, and its popularity in the Middle Ages can be judged from the fact that it survives in seventy-five manuscripts. It is included in The Oxford Book of Welsh Verse.

The plowboy trope appears in Christian rhetoric and literature in the form of various bucolic, lowly, pious or even unsavoury characters who would benefit from being exposed to Scripture in the vernacular. The plowboy trope is an anti-elitist trope dating back at least 1600 years.