Antonio Canova was an Italian Neoclassical sculptor, famous for his marble sculptures. Often regarded as the greatest of the Neoclassical artists, his sculpture was inspired by the Baroque and the classical revival, and has been characterised as having avoided the melodramatics of the former, and the cold artificiality of the latter.

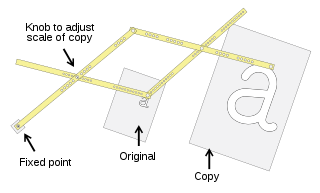

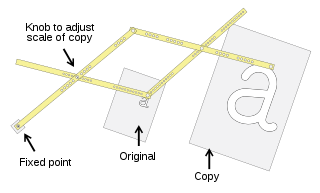

A pantograph is a mechanical linkage connected in a manner based on parallelograms so that the movement of one pen, in tracing an image, produces identical movements in a second pen. If a line drawing is traced by the first point, an identical, enlarged, or miniaturized copy will be drawn by a pen fixed to the other. Using the same principle, different kinds of pantographs are used for other forms of duplication in areas such as sculpture, minting, engraving, and milling.

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sculptural processes originally used carving and modelling, in stone, metal, ceramics, wood and other materials but, since Modernism, there has been an almost complete freedom of materials and process. A wide variety of materials may be worked by removal such as carving, assembled by welding or modelling, or moulded or cast.

David is a masterpiece of Renaissance sculpture, created in marble between 1501 and 1504 by the Italian artist Michelangelo. David is a 5.17-metre marble statue of the Biblical figure David, a favoured subject in the art of Florence.

Marble sculpture is the art of creating three-dimensional forms from marble. Sculpture is among the oldest of the arts. Even before painting cave walls, early humans fashioned shapes from stone. From these beginnings, artifacts have evolved to their current complexity.

Stonemasonry or stonecraft is the creation of buildings, structures, and sculpture using stone as the primary material. It is one of the oldest activities and professions in human history. Many of the long-lasting, ancient shelters, temples, monuments, artifacts, fortifications, roads, bridges, and entire cities were built of stone. Famous works of stonemasonry include the Egyptian pyramids, the Taj Mahal, Cusco's Incan Wall, Easter Island's statues, Angkor Wat, Borobudur, Tihuanaco, Tenochtitlan, Persepolis, the Parthenon, Stonehenge, the Great Wall of China, Chartres Cathedral.

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "render" commonly refers to external applications. Another imprecise term used for the material is stucco, which is also often used for plasterwork that is worked in some way to produce relief decoration, rather than flat surfaces.

Bronze is the most popular metal for cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply a "bronze". It can be used for statues, singly or in groups, reliefs, and small statuettes and figurines, as well as bronze elements to be fitted to other objects such as furniture. It is often gilded to give gilt-bronze or ormolu.

Relief is a sculptural technique where the sculpted elements remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term relief is from the Latin verb relevo, to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the sculpted material has been raised above the background plane. What is actually performed when a relief is cut in from a flat surface of stone or wood is a lowering of the field, leaving the unsculpted parts seemingly raised. The technique involves considerable chiselling away of the background, which is a time-consuming exercise. On the other hand, a relief saves forming the rear of a subject, and is less fragile and more securely fixed than a sculpture in the round, especially one of a standing figure where the ankles are a potential weak point, especially in stone. In other materials such as metal, clay, plaster stucco, ceramics or papier-mâché the form can be just added to or raised up from the background, and monumental bronze reliefs are made by casting.

Stone carving is an activity where pieces of rough natural stone are shaped by the controlled removal of stone. Owing to the permanence of the material, stone work has survived which was created during our prehistory or past time.

This page describe terms and jargon related to sculpture and sculpting.

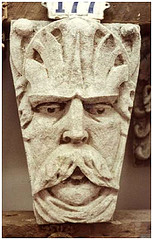

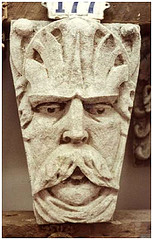

Architectural sculpture is a general categorization used to describe items used for the decoration of buildings and structures. In the United States, the term encompasses both sculpture that is attached to a building and free-standing pieces that are a part of an architects design.

The Greek Slave is a marble sculpture by the American sculptor Hiram Powers. It was one of the best-known and critically acclaimed American artworks of the nineteenth century, and is among the most popular American sculptures ever. It was the first publicly exhibited, life-size, American sculpture depicting a fully nude female figure. Powers originally modeled the work in clay, in Florence, Italy, completing it on March 12, 1843. The first marble version of the sculpture was completed by Powers' studio in 1844 and is now in Raby Castle, England.

The fireplace mantel or mantelpiece, also known as a chimneypiece, originated in medieval times as a hood that projected over a fire grate to catch the smoke. The term has evolved to include the decorative framework around the fireplace, and can include elaborate designs extending to the ceiling. Mantelpiece is now the general term for the jambs, mantel shelf, and external accessories of a fireplace. For many centuries, the chimneypiece was the most ornamental and most artistic feature of a room, but as fireplaces have become smaller, and modern methods of heating have been introduced, its artistic as well as its practical significance has lessened.

A Stone sculpture is an object made of stone which has been shaped, usually by carving, or assembled to form a visually interesting three-dimensional shape. Stone is more durable than most alternative materials, making it especially important in architectural sculpture on the outside of buildings.

Theodore Golubic was an American sculptor and painter. He studied sculpture at the Syracuse University under Ivan Meštrović and eventually became his assistant at Syracuse and Assistant Fellowship to Meštrović at Notre Dame University. He was a guest teacher at Notre Dame and PBS "Art School of the Air." After receiving his Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Notre Dame. Later in his career he created three-dimensional sculpture to four-dimensional art that involved shadow and light. He is referenced in Who's Who in American Art, exhibited and commissioned both regionally and nationally. As a creative artist, he combined both science and art, and received five US technology patents in semiconductors, one for a three-dimensional packaging design.

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a casting, which is ejected or broken out of the mold to complete the process. Casting materials are usually metals or various time setting materials that cure after mixing two or more components together; examples are epoxy, concrete, plaster and clay. Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be otherwise difficult or uneconomical to make by other methods. Heavy equipment like machine tool beds, ships' propellers, etc. can be cast easily in the required size, rather than fabricating by joining several small pieces.

Abraham Lincoln (1920) is a colossal seated figure of the 16th President of the United States Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) sculpted by Daniel Chester French (1850–1931) and carved by the Piccirilli Brothers. It is in the Lincoln Memorial, on the National Mall, Washington, D.C., United States, and was unveiled in 1922. The work follows in the Beaux Arts and American Renaissance style traditions.

Robert Treat Paine (1870–1946) was an American sculptor.