Ao (daylight) is one of the primal deities who are the unborn forces of nature in Māori mythology. Ao is the personification of light, clouds, and the ordinary world, as opposed to darkness and the underworld.

Whiro-te-tipua is the lord of darkness and embodiment of all evil in Māori mythology. He inhabits the underworld and is responsible for the ills of all people, a contrast to his brother and enemy Tāne.

Sir Āpirana Turupa Ngata was a prominent New Zealand statesman. He has often been described as the foremost Māori politician to have served in parliament in the mid-20th century, and is also known for his work in promoting and protecting Māori culture and language. His legacy is one of the most prominent of any New Zealand leader in the 20th century, and is commemorated by his depiction on the fifty dollar note.

Tūrangawaewae Marae is located in the town of Ngāruawāhia in the Waikato region of the North Island of New Zealand. A very significant marae, it is the headquarters for the Māori King Movement and the official residence and reception centre of the head of the Kīngitanga, the current Māori King, Tūheitia Paki.

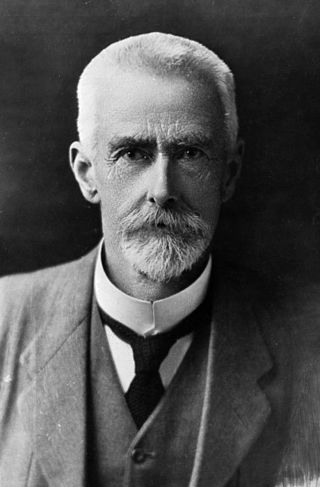

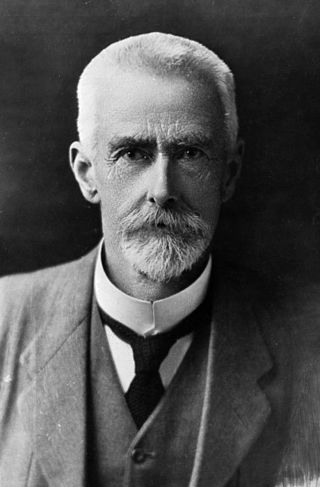

Sir Peter Henry Buck, also known as Te Rangi Hīroa or Te Rangihīroa, was a New Zealand doctor and a prominent anthropologist who served many roles through his life.

Sir Māui Wiremu Pita Naera Pōmare was a New Zealand medical doctor and politician, being counted among the more prominent Māori political figures. He is particularly known for his efforts to improve Māori health and living conditions. However, Pōmare's career was not without controversy: he negotiated the effective removal of the last of Taranaki Māori land from its native inhabitants – some 18,000 acres – in a move which has been described as the "final disaster" for his people. He was a member of the Ngati Mutunga iwi originally from North Taranaki; he later lived in Wellington and the Chatham Islands after the 1835 invasion.

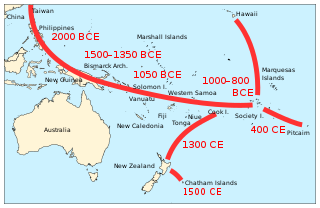

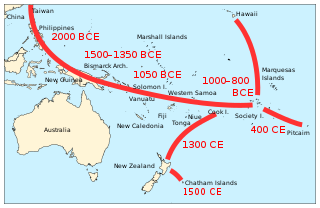

Various Māori traditions recount how their ancestors set out from their homeland in waka hourua, large twin-hulled ocean-going canoes (waka). Some of these traditions name a homeland called Hawaiki.

Io Matua Kore is often understood as the supreme being in Polynesian narrative, particularly of the Māori people.

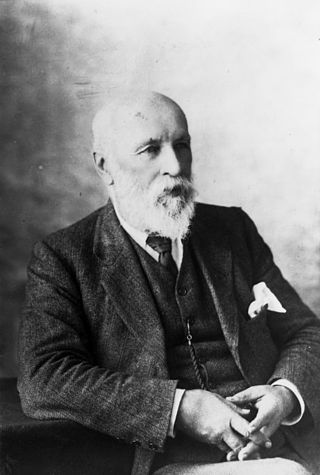

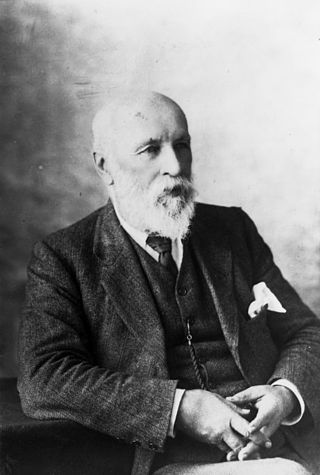

Stephenson Percy Smith was a New Zealand ethnologist and surveyor. He founded The Polynesian Society.

Elsdon Best was an ethnographer who made important contributions to the study of the Māori of New Zealand.

Edward Robert Tregear, Ordre des Palmes académiques was a New Zealand public servant and scholar. He was an architect of New Zealand's advanced social reforms and progressive labour legislation during the 1890s.

Rarohenga is the subterranean realm where spirits of the deceased dwell after death, according to Māori oral tradition. The underworld is ruled by Hine-nui-te-pō, the goddess of death and night. Additional occupants include guardians, gods, goddesses, holy chiefs and nobles (rangatira), and the tūrehu, who are described as celestial, fairy-like people. Rarohenga is predominantly depicted as a place of peace and light. As articulated by Māori ethnographer Elsdon Best: It is a place where darkness is unknown. "This is the reason why, of all spirits of the dead since the time of Hine-ahuone…, not a single one has ever returned hither to dwell in this world".

Kurī is the Māori name for the extinct Polynesian dog. It was introduced to New Zealand by the Polynesian ancestors of the Māori during their migration from East Polynesia in the 13th century AD. According to Māori tradition, the demigod Māui transformed his brother-in-law Irawaru into the first dog.

Māori are the indigenous Polynesian people of mainland New Zealand. Māori originated with settlers from East Polynesia, who arrived in New Zealand in several waves of canoe voyages between roughly 1320 and 1350. Over several centuries in isolation, these settlers developed their own distinctive culture, whose language, mythology, crafts, and performing arts evolved independently from those of other eastern Polynesian cultures. Some early Māori moved to the Chatham Islands, where their descendants became New Zealand's other indigenous Polynesian ethnic group, the Moriori.

Bruce Grandison Biggs was an influential figure in the academic field of Māori studies in New Zealand. The first academic appointed (1950) to teach the Māori language at a New Zealand university, he taught and trained a whole generation of Māori academics.

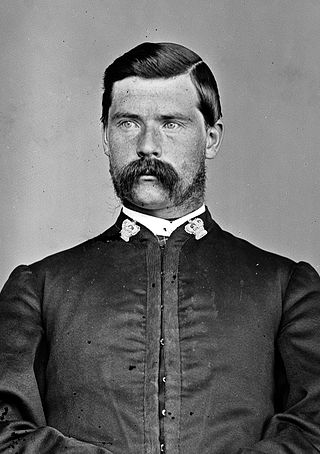

Walter Edward Gudgeon was a farmer, soldier, historian, land court judge, and colonial administrator.

Since the early 1900s the fact that Polynesians were the first ethnic group to settle in New Zealand has been accepted by archaeologists and anthropologists. Before that time and until the 1920s, however, a small group of prominent anthropologists proposed that the Moriori people of the Chatham Islands represented a pre-Māori group of people from Melanesia, who once lived across all of New Zealand and were replaced by the Māori. While this idea lost favour among academics, it was widely and controversially incorporated into school textbooks during the 20th century. Today, such theories are considered to be pseudohistorical and negationist by scholars and historians and racist by many observers, having been used to justify settler colonalism.

Mātauranga is a modern term for the traditional knowledge of the Māori people of New Zealand. Māori traditional knowledge is multi-disciplinary and holistic, and there is considerable overlap between concepts. It includes environmental stewardship and economic development, with the purpose of preserving Māori culture and improving the quality of life of the Māori people over time.

Te Ata-inutai was a Māori rangatira (chieftain) of the Ngāti Raukawa iwi in the Tainui tribal confederation based at Whare-puhunga in the Waikato region of New Zealand. He led an attack against Ngāti Tūwharetoa on the south shore of Lake Taupō, as a result of disputes arising from the Ngāti Tama–Ngāti Tūwharetoa War and forged a peace treaty with the Tūwharetoa chieftain Te Rangi-ita, but was ultimately murdered in his old age by members of Tūwharetoa in vengeance for his earlier attack. He probably lived in the early seventeenth century.

Whiti-patatō was a rangatira (chieftain) of Ngāti Raukawa, based at Whare-puhunga in the Waikato region of New Zealand, who led an attack on Ngāti Tūwharetoa to avenge the death of the Ngāti Raukawa rangatira, Te Ata-inutai, probably in the mid-seventeenth century.