Related Research Articles

Pope Benedict XV, born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his death in January 1922. His pontificate was largely overshadowed by World War I and its political, social, and humanitarian consequences in Europe.

Pope Pius XI, born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City from its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929. He assumed as his papal motto "Pax Christi in Regno Christi", translated "The Peace of Christ in the Kingdom of Christ".

Pietro Gasparri, GCTE was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV and Pope Pius XI.

The Russian Greek Catholic Church, Russian Byzantine Catholic Church or simply Russian Catholic Church, is a sui iuris Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic jurisdiction of the worldwide Catholic Church. Historically, it represents the first reunion of members of the Russian Orthodox Church with the Catholic Church. It is in full communion with and subject to the authority of the Pope of Rome as defined by Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches.

After the October Revolution of November 7, 1917 there was a movement within the Soviet Union to unite all of the people of the world under Communist rule. This included the Eastern bloc countries as well as the Balkan States. Communism as interpreted by Vladimir Lenin and his successors in the Soviet government required the abolition of religion and to this effect the Soviet government launched a long-running campaign to eliminate religion from society. Since some of these Slavic states tied their ethnic heritage to their ethnic churches, both the peoples and their churches were targeted by the Soviets.

Pope Pius XII and Russia describes relations of the Vatican with the Soviet Union, Russia, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Eastern Catholic Churches resulting in the eradication of the Church in most parts of the Soviet Union during the Stalinist era. Most persecutions of the Church occurred during the pontificate of Pope Pius XII.

Persecutions against the Catholic Church took place during the papacy of Pope Pius XII (1939–1958). Pius' reign coincided with World War II (1939–1945), followed by the commencement of the Cold War and the accelerating European decolonisation. During his papacy, the Catholic Church faced persecution under Fascist and Communist governments.

The Vatican and Eastern Europe (1846–1958) describes the relations from the pontificate of Pope Pius IX (1846–1878) through the pontificate of Pope Pius XII (1939–1958). It includes the relations of the Church State (1846–1870) and the Vatican (1870–1958) with Russia (1846–1918), Lithuania (1922–1958) and Poland (1918–1958).

Pope Pius IX and Russia includes the relations between the Pontiff and the Russian Empire during the years 1846–1878.

Holy See–Russia relations are the bilateral relations between the Holy See and Russia. The Holy See has an Apostolic Nunciature in Moscow. Russia has a permanent representative to the Holy See based in Rome.

Eastern Catholic victims of Soviet persecutions include bishops and others among the tens of thousands of victims of Soviet persecutions from 1918 to approximately 1980, under the state ideology of Marxist–Leninist atheism.

19th-century German philosopher Karl Marx, the founder and primary theorist of Marxism, viewed religion as "the soul of soulless conditions" or the "opium of the people". According to Karl Marx, religion in this world of exploitation is an expression of distress and at the same time it is also a protest against the real distress. In other words, religion continues to survive because of oppressive social conditions. When this oppressive and exploitative condition is destroyed, religion will become unnecessary. At the same time, Marx saw religion as a form of protest by the working classes against their poor economic conditions and their alienation. Denys Turner, a scholar of Marx and historical theology, classified Marx's views as adhering to Post-Theism, a philosophical position that regards worshipping deities as an eventually obsolete, but temporarily necessary, stage in humanity's historical spiritual development.

Holy See–Soviet Union relations were marked by long-standing ideological disagreements between the Catholic Church and the Soviet Union. The Holy See attempted to enter in a pragmatic dialogue with Soviet leaders during the papacies of John XXIII and Paul VI. In the 1990s, Pope John Paul II's diplomatic policies were cited as one of the principal factors that led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The relationship between Pope Pius XI and Poland is often considered to have been good, as Church life in Poland flourished during his pontificate.

The Roman Catholic Church in the 20th century had to respond to the challenge of increasing secularization of Western society and persecution resulting from great social unrest and revolutions in several countries. It instituted many reforms, particularly in the 1970s under the Vatican II Council, in order to modernize practices and positions. In this period, Catholic missionaries in the Far East worked to improve education and health care, while evangelizing peoples and attracting numerous followers in China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan.

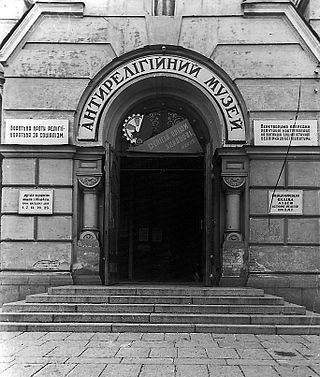

The USSR anti-religious campaign (1921–1928) was a campaign of anti-religious persecution against churches and Christian believers by the Soviet government following the initial anti-religious campaign during the Russian Civil War. The elimination of most religion and its replacement with deism, agnosticism and atheism supported with a materialist world view was a fundamental ideological goal of the state. To this end, the state conducted anti-religious persecutions against believers that were meant to hurt and destroy religion. It was never made illegal to be a believer or to have religion, and so the activities of this campaign were often veiled under other pretexts that the state invoked or invented in order to justify its activities.

In the time of Pope Pius IX, Poland had long been partitioned among three neighbouring powers and no longer existed as an independent country. The Polish people lived under the rule of the Russian Empire, the Austrian Empire and Prussia.

The Polish anti-religious campaign was initiated by the communist government in Poland which, under the doctrine of Marxism, actively advocated for the disenfranchisement of religion and planned atheisation. To this effect the regime conducted anti-religious propaganda and persecution of clergymen and monasteries. As in most other Communist countries, religion was not outlawed as such and was permitted by the constitution, but the state attempted to achieve an atheistic society.

The anti-religious campaign of Communist Romania was initiated by the People's Republic of Romania and continued by the Socialist Republic of Romania, which under the doctrine of Marxist–Leninist atheism took a hostile stance against religion and set its sights on the ultimate goal of an atheistic society, wherein religion would be recognized as the ideology of the bourgeoisie.

Anti-Catholicism in the Soviet Union, including the Soviet Anti-Catholic Campaigns, refer to those concerted efforts taken by the Soviet Union to defame, undermine, or otherwise decrease or limit the role of the Catholic Church in Europe.

References

- ↑ Communist Manifesto , 1848

- ↑ The Historical Institute of the Soviet Academy of Sciences 1953, 461

- ↑ Engels, die Entwicklung des Sozialismus von der Utopie zur Wissenschaft, ausgewählte Schriften Berlin, 1953, 93

- ↑ Clarkson 571

- ↑ Clarkson, 493

- ↑ Karl Marx

- ↑ he wrote to his wife, My thinking compels me to be merciless and I have the firm will to follow my thinking to the utmost. Clarkson 492

- ↑ Clarkson 493

- ↑ Clarkson, 493, 572

- ↑ Schmidlin III 308

- ↑ Fr. von Lama, Papst und Kurie in ihrer Politik nach dem Weltkrieg, Illertissen, 1925, p.362

- ↑ Schmidlin III, 308