The Balkan Wars were a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defeated it, in the process stripping the Ottomans of their European provinces, leaving only Eastern Thrace under Ottoman control. In the Second Balkan War, Bulgaria fought against the other four original combatants of the first war. It also faced an attack from Romania from the north. The Ottoman Empire lost the bulk of its territory in Europe. Although not involved as a combatant, Austria-Hungary became relatively weaker as a much enlarged Serbia pushed for union of the South Slavic peoples. The war set the stage for the July crisis of 1914 and thus served as a prelude to the First World War.

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo was a French Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms.

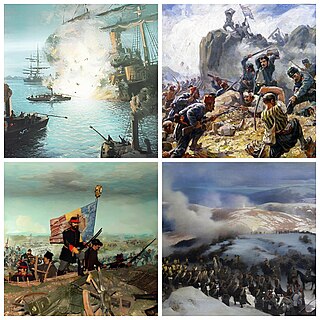

The Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) was a conflict between the Ottoman Empire and a coalition led by the Russian Empire which included Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro. Additional factors included the Russian goals of recovering territorial losses endured during the Crimean War of 1853–1856, re-establishing itself in the Black Sea and supporting the political movement attempting to free Balkan nations from the Ottoman Empire. The Romanian army had around 114,000 soldiers in the war. In Romania the war is called the Russo-Romanian-Turkish War (1877–1878) or the Romanian War of Independence (1877–1878).

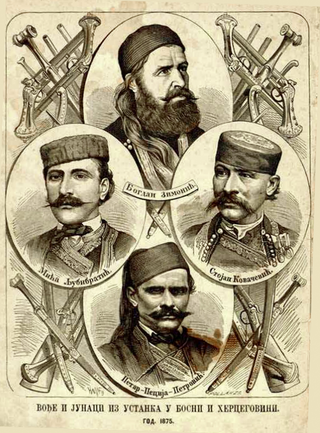

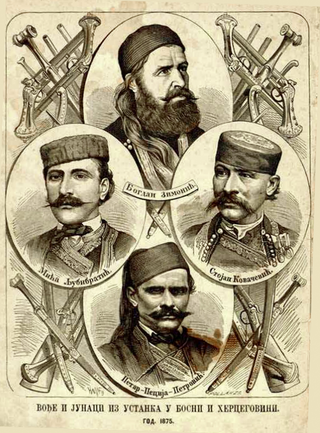

The Herzegovina uprising was an uprising led by the Christian Serb population against the Ottoman Empire, firstly and predominantly in Herzegovina, from where it spread into Bosnia and Raška. It broke out in the summer of 1875, and lasted in some regions up to the beginning of 1878. It was followed by the Bulgarian Uprising of 1876, and coincided with Serbian-Turkish wars (1876–1878), all of those events being part of the Great Eastern Crisis (1875–1878).

The First Serbian Uprising was an uprising of Serbs in Orašac against the Ottoman Empire from 14 February 1804, to 7 October 1813. The uprising began as a local revolt against the Dahije, who had seized power in a coup d'état. It later evolved into a war for independence, known as the Serbian Revolution, after more than three centuries of Ottoman Empire rule and brief Austrian occupations.

The Ottoman Empire was founded c. 1299 by Osman I as a small beylik in northwestern Asia Minor just south of the Byzantine capital Constantinople. In 1326, the Ottomans captured nearby Bursa, cutting off Asia Minor from Byzantine control. The Ottomans first crossed into Europe in 1352, establishing a permanent settlement at Çimpe Castle on the Dardanelles in 1354 and moving their capital to Edirne (Adrianople) in 1369. At the same time, the numerous small Turkic states in Asia Minor were assimilated into the budding Ottoman sultanate through conquest or declarations of allegiance.

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911 to 18 October 1912. As a result of this conflict, Italy captured the Ottoman Tripolitania Vilayet, of which the main sub-provinces were Fezzan, Cyrenaica, and Tripoli itself. These territories became the colonies of Italian Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, which would later merge into Italian Libya.

In diplomatic history, the Eastern question was the issue of the political and economic instability in the Ottoman Empire from the late 18th to early 20th centuries and the subsequent strategic competition and political considerations of the European great powers in light of this. Characterized as the "sick man of Europe", the relative weakening of the empire's military strength in the second half of the nineteenth century threatened to undermine the fragile balance of power system largely shaped by the Concert of Europe. The Eastern question encompassed myriad interrelated elements: Ottoman military defeats, Ottoman institutional insolvency, the ongoing Ottoman political and economic modernization programme, the rise of ethno-religious nationalism in its provinces, and Great Power rivalries. In an attempt to triangulate between these various concerns, the historian Leslie Rogne Schumacher has proposed the following definition of the Eastern Question:

The "Eastern Question" refers to the events and the complex set of dynamics related to Europe's experience of and stake in the decline in political, military and economic power and regional significance of the Ottoman Empire from the latter half of the eighteenth century to the formation of modern Turkey in 1923.

The April Uprising was an insurrection organised by the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire from April to May 1876. The rebellion was suppressed by irregular Ottoman bashi-bazouk units that engaged in indiscriminate slaughter of both rebels and non-combatants.

Russo-Turkish wars or Russo-Ottoman wars were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European history. Except for four wars, the conflicts ended in losses for the Ottoman Empire, which was undergoing a long period of stagnation and decline; conversely, they showcased the ascendancy of Russia as a European power after the modernization efforts of Peter the Great in the early 18th century.

Actes et Paroles is a collection of Victor Hugo's political utterances from 1841 to 1876. It contains his speeches, largely unchanged, and a record of his political career.

The Armenian question was the debate following the Congress of Berlin in 1878 as to how the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire should be treated. The term became commonplace among diplomatic circles and in the popular press. In specific terms, the Armenian question refers to the protection and the freedoms of Armenians from their neighboring communities. The Armenian question explains the 40 years of Armenian–Ottoman history in the context of English, German, and Russian politics between 1877 and 1914. In 1915, the leadership of the Committee of Union and Progress, which controlled the Ottoman government, decided to end the Armenian question permanently by killing and expelling most Armenians from the empire, in the Armenian genocide.

The massacres of Albanians in the Balkan Wars were perpetrated on several occasions by the Serbian and Montenegrin armies and paramilitaries during the conflicts that occurred in the region between 1912 and 1913. During the 1912–13 First Balkan War, Serbia and Montenegro committed a number of war crimes against the Albanian population after expelling Ottoman Empire forces from present-day Albania, Kosovo, and North Macedonia, which were reported by the European, American and Serbian opposition press. Most of the crimes occurred between October 1912 and the summer of 1913. The goal of the forced expulsions and massacres was statistical manipulation before the London Ambassadors Conference to determine the new Balkan borders. According to contemporary accounts, around 20,000 to 25,000 Albanians were killed in the Kosovo Vilayet during the first two to four months, before the violence climaxed. The total number of Albanians that were killed in Kosovo and Macedonia or in all Serbian occupied regions during the Balkan Wars is estimated to be at least 120,000. Most of the victims were children, women and the elderly. In addition to the massacres, some civilians had their lips and noses severed. Multiple historians, scholars, and contemporary accounts refer to or characterize the massacres as a genocide of Albanians in the Balkan Wars. Further massacres against Albanians occurred during the First World War and continued during the interwar period.

Turco-Albanian is an ethnographic, religious, and derogatory term used by Greeks for Muslim Albanians since 1715. In a broader sense, the term included both Muslim Albanian and Turkish political and military elites of the Ottoman administration in the Balkans. The term is derived from an identification of Muslims with Ottomans and/or Turks because of the Ottoman Empire's administrative millet system of classifying peoples according to religion in which the Muslim millet played the leading role. From the mid-19th century, the term Turk and from the late 19th century onwards, the derivative term Turco-Albanian has been used as a pejorative term, phrase and or expression for Muslim Albanian individuals and communities. The term has also been noted to be unclear, ideologically and sentimentally charged, and an imperialist and racialist expression.

Serbophilia is the admiration, appreciation or emulation of non-Serbian person who expresses a strong interest, positive predisposition or appreciation for the Serbian people, Serbia, Republika Srpska, Serbian language, culture or history. Its opposite is Serbophobia.

During the decline and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, Muslim inhabitants living in Muslim-minority territories previously under Ottoman control often found themselves persecuted after borders were re-drawn. These populations were subject to genocide, expropriation, massacres, religious persecution, mass rape, and ethnic cleansing.

The massacre of Phocaea occurred in June 1914, as part of the ethnic cleansing policies of the Ottoman Empire that included exile, massacre and deportations. It was perpetrated by irregular Turkish bands against the predominantly ethnic Greek town of Phocaea, modern Foça, on the east coast of the Aegean Sea. The massacre was part of a wider anti-Greek campaign of genocide launched by the Young Turk Ottoman authorities, which included boycott, intimidation, forced deportations and mass killings; and was one of the worst attacks during the summer of 1914.

The persecution of Eastern Orthodox Christians is the religious persecution which has been faced by the clergy and the adherents of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Eastern Orthodox Christians have been persecuted during various periods in the history of Christianity when they lived under the rule of non-Orthodox Christian political structures. In modern times, anti-religious political movements and regimes in some countries have held an anti-Orthodox stance.

Acts of violence were committed against ethnic Serbs, primarily by Albanians, during the final stages of the Ottoman Empire and their control of parts of the Balkans.

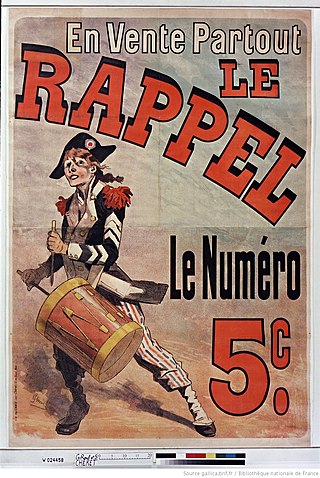

Le Rappel was a French daily newspaper founded in 1869 by Victor Hugo's sons Charles and François-Victor and three others. It was published from the end of the French Second Empire until 1933. At the start of the Third Republic, it embodied a radical-republican tendency and as such was highly contested by the French government.