The First Council of the Lateran was the 9th ecumenical council recognised by the Catholic Church. It was convoked by Pope Callixtus II in December 1122, immediately after the Concordat of Worms. The council sought to bring an end to the practice of the conferring of ecclesiastical benefices by people who were laymen, free the election of bishops and abbots from secular influence, clarify the separation of spiritual and temporal affairs, re-establish the principle that spiritual authority resides solely in the Church and abolish the claim of the Holy Roman Emperor to influence papal elections.

Einsiedeln Abbey is a Catholic monastery administered by the Benedictine Order in the village of Einsiedeln, Switzerland.

Lorsch Abbey, otherwise the Imperial Abbey of Lorsch, is a former Imperial abbey in Lorsch, Germany, about 10 km (6.2 mi) east of Worms. It was one of the most important monasteries of the Carolingian Empire. Even in its ruined state, its remains are among the most important pre-Romanesque–Carolingian style buildings in Germany.

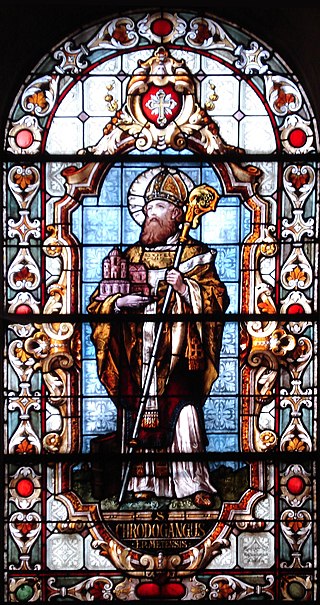

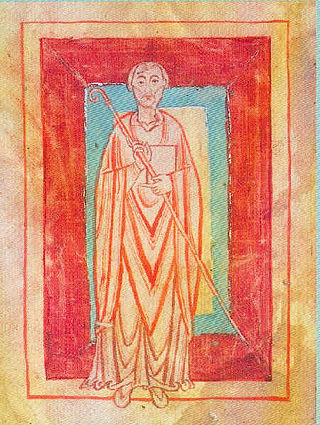

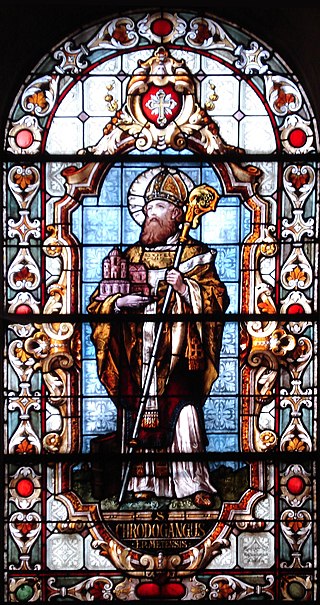

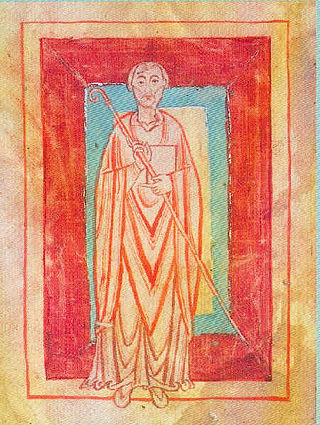

Chrodegang was the Frankish Bishop of Metz from 742 or 748 until his death. He served as chancellor for his kinsman, Charles Martel. Chrodegang is claimed to be a progenitor of the Frankish dynasty of the Robertians. He is recognized as a saint in the Catholic Church.

Lorsch is a town in the Bergstraße district in Hessen, Germany, 60 km south of Frankfurt. Lorsch is well known for the Lorsch Abbey, which has been named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Alpirsbach Abbey is a former Benedictine monastery and later Protestant seminary located at Alpirsbach in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The monastery was established in the late 11th century and possessed considerable freedoms for an ecclesiastical property at that time, but in the 13th century it became a de facto possession of the Dukes of Teck and then the County of Württemberg. In the 15th century, the monastery enjoyed economic prosperity and was expanded but was dissolved with the conversion of the by-then Duchy of Württemberg to Lutheranism in the 16th century. The monastery became a seminary and boarding school until the 17th century and was physically reduced over the 19th century by land sales and demolition. Over the second half of the 20th century, the monastery was turned into a cultural fixture with annual concerts of Classical music and a museum of its history.

Amorbach Abbey was a Benedictine imperial abbey of the Holy Roman Empire located at Amorbach. It was later the residence of the rulers of the short-lived Principality of Leiningen, before that became part of the Kingdom of Bavaria, and its historic buildings still belong to the princely family.

Ottobeuren is a Benedictine abbey, located in Ottobeuren, near Memmingen in the Bavarian Allgäu, Germany.

William of Hirsau was a Benedictine abbot and monastic reformer. He was abbot of Hirsau Abbey, for whom he created the Constitutiones Hirsaugienses, based on the uses of Cluny, and was the father of the Hirsau Reforms, which influenced many Benedictine monasteries in Germany. He supported the papacy in the Investiture Controversy. In the Roman Catholic Church, he is a Blessed, the second of three steps toward recognition as a saint.

Hirsau Abbey, formerly known as Hirschau Abbey, was once one of the most important Benedictine abbeys of Germany. It is located in the Hirsau borough of Calw on the northern slopes of the Black Forest mountain range, in the present-day state of Baden-Württemberg. In the 11th and 12th century, the monastery was a centre of the Cluniac Reforms, implemented as "Hirsau Reforms" in the German lands by William of Hirsau. The complex was devastated during the War of the Palatine Succession in 1692 and not rebuilt. The ruins served as a quarry for a period of time.

Saint Emmeram's Abbey was a Benedictine monastery founded around 739 at Regensburg in Bavaria at the grave of the itinerant Frankish bishop Saint Emmeram. The original abbey church is now a parish church named St. Emmeram's Basilica. The other buildings on the site form a large complex known as Schloss Thurn und Taxis or Schloss St. Emmeram, which has served as the main residence of the Thurn und Taxis princely family since the early 19th century.

Göttweig Abbey is a Benedictine monastery near Krems in Lower Austria. It was founded in 1083 by Altmann, Bishop of Passau.

Saint Paul's Abbey in Lavanttal is a Benedictine monastery established in 1091 near the present-day market town of Sankt Paul im Lavanttal in the Austrian state of Carinthia. The premises centered on the Romanesque monastery church were largely rebuilt in a Baroque style in the 17th century.

Ellwangen Abbey was the earliest Benedictine monastery established in the Duchy of Swabia, at the present-day town of Ellwangen an der Jagst, Baden-Württemberg, about 100 km (60 mi) north-east of Stuttgart.

Carolingian architecture is the style of north European Pre-Romanesque architecture belonging to the period of the Carolingian Renaissance of the late 8th and 9th centuries, when the Carolingian dynasty dominated west European politics. It was a conscious attempt to emulate Roman architecture and to that end it borrowed heavily from Early Christian and Byzantine architecture, though there are nonetheless innovations of its own, resulting in a unique character.

Weissenau Abbey was an Imperial abbey (Reichsabtei) of the Holy Roman Empire located near Ravensburg in the Swabian Circle. The abbey, a Premonstratensian monastery, was an Imperial Estate and therefore its abbot had seat and vote in the Reichstag as a prelate of the Swabian Bench. The abbey existed from 1145 until the secularisation of 1802-1803.

The Great Saint Martin Church is a Romanesque Catholic church in Cologne, Germany. Its foundations rest on remnants of a Roman chapel, built on what was then an island in the Rhine. The church was later transformed into a Benedictine monastery. The current buildings, including a soaring crossing tower that is a landmark of Cologne's Old Town, were erected between 1150-1250. The architecture of its eastern end forms a triconch or trefoil plan, consisting of three apses around the crossing, similar to that at St. Maria im Kapitol. The church was badly damaged in World War II; restoration work was completed in 1985.

Cancor was a Frankish count associated with Lorsch Abbey. He was son of a noble lady Williswinda. As her only known husband before she was widowed was named Robert, it has been proposed that Cancor was son to Robert I, Count of Hesbaye, who was also alive in the 8th century.

Michaelsberg Abbey or Michelsberg Abbey, also St. Michael's Abbey, Bamberg is a former Benedictine monastery in Bamberg in Bavaria, Germany. After its dissolution in 1803 the buildings were used for the almshouse Vereinigtes Katharinen- und Elisabethen-Spital, which is still there as a retirement home. The former abbey church remains in use as the Michaelskirche.

Ulrich Stutz was a Swiss-German jurist and historian and pioneering scholar in the academic study of canon law. He is associated in particular with the theory of the proprietary church (Eigenkirche) and its role in the development of Christianity in medieval Europe.