A city gate is a gate which is, or was, set within a city wall. It is a type of fortified gateway.

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See, better known as Seville Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Seville, Andalusia, Spain. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along with the adjoining Alcázar palace complex and the General Archive of the Indies. It is one of the largest churches in the world as well as the largest Gothic church.

Arcos de la Frontera is a town and municipality in the Sierra de Cádiz comarca, province of Cádiz, in Andalusia, Spain. It is located on the northern, western and southern banks of the Guadalete river, which flows around three sides of the city under towering vertical cliffs, to Jerez and on to the Bay of Cádiz. The town commands a fine vista atop a sandstone ridge, from which the peak of San Cristóbal and the Guadalete Valley can be seen. The town gained its name by being the frontier of Spain's 13th-century battle with the Moors.

The Albaicín, also known as Albayzín, is a district of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. It is centered around a hill on the north side of the Darro River which passes through the city. The neighbourhood is notable for its historic monuments and for largely retaining its medieval street plan dating back to the Nasrid period, although it nonetheless went through many physical and demographic changes after the end of the Reconquista in 1492. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 1994, as an extension of the historic site of the nearby Alhambra.

Sos del Rey Católico is a historic town and municipality in the Cinco Villas comarca, province of Zaragoza, in Aragon, Spain.

The history of Carmona begins at one of the oldest urban sites in Europe, with nearly five thousand years of continuous occupation on a plateau rising above the vega (plain) of the River Corbones in Andalusia, Spain. The city of Carmona lies thirty kilometres from Seville on the highest elevation of the sloping terrain of the Los Alcores escarpment, about 250 metres above sea level. Since the first appearance of complex agricultural societies in the Guadalquivir valley at the beginning of the Neolithic period, various civilizations have had an historical presence in the region. All the different cultures, peoples, and political entities that developed there have left their mark on the ethnographic mosaic of present-day Carmona. Its historical significance is explained by the advantages of its location. The easily defended plateau on which the city sits, and the fertility of the land around it, made the site an important population center. The town's strategic position overlooking the vega was a natural stronghold, allowing it to control the trails leading to the central plateau of the Guadalquivir valley, and thus access to its resources.

The Gate of the Ears, also known as the Arc of the Ears or Bib-Arrambla Gate, was a city gate of Granada. Built in the 11th or 12th century, it stood at the corner of Plaza de Bib-Rambla and Calle Salamanca. During the 19th century, the gate became the subject of several major controversies, and in 1884 it was demolished.

The Walls of Seville are a series of defensive walls surrounding the Old Town of Seville. The city has been surrounded by walls since the Roman period, and they were maintained and modified throughout the subsequent Visigoth, Islamic and finally Castilian periods. The walls remained intact until the 19th century, when they were partially demolished after the revolution of 1868. Some parts of the walls still exist, especially around the Alcázar of Seville and some curtain walls in the barrio de la Macarena.

The Christian Walls of Madrid, also known as the Medieval Walls, were built in Madrid, Spain between the 11th and 12th centuries, once the city passed to the Crown of Castile. They were built as an extension of the original 9th-century Muslim Walls of Madrid to accommodate the new districts which emerged after the Reconquista.

The Walls of Philip II were walls in the city of Madrid that Philip II, in 1566, constructed for fiscal and sanitary control. The walls enclosed an area of about 125 ha.

The Palacio de la Ribera was the summer residence of Philip III in Valladolid. It was built in the 17th century (1602-1605) as part of a process of urban transformation upon the establishment of the Spanish Court in Valladolid between 1601 and 1606. The palace was situated at the Huerta del Rey neighborhood, located across the Parque de las Moreras on the right bank of the Pisuerga river. The palace grounds extended from the Puente Mayor to Ribera de Don Periáñez del Corral and delimited at both sides by the Pisuerga river and the Camino del Monasterio del Prado. The palace was gradually abandoned until it became part of the destroyed cultural heritage of Valladolid in 1761. Some ruins of the building are still preserved.

The Puerta de la Macarena, also known as Arco de la Macarena, is one of the only three city gates that remain today of the original walls of Seville, alongside the Postigo del Aceite and the Puerta de Córdoba. It is located in the calle Resolana, within the barrio de San Gil, which belongs to the district of Casco Antiguo of the city of Seville, in Andalusia, Spain. The gate faces the Basílica de La Macarena, which houses the image of the Our Lady of la Esperanza Macarena, one of the most characteristic images of the Holy Week in Seville.

The triumphal arches for the arrival of Isabel II to Seville were triumphal arches that rose in the city of Seville in September 1862 to welcome Queen Isabel II of Spain and her husband Don Francis of Assisi, who arrived on the day 17 to the old former Cordoba Station located at the Campo de Marte, where it had arranged one arch, after which was placed in the place a street of flags and pennants by which marched the sovereigns together with the Dukes of Montpensier, who had come welcome to them.

The Postigo del Aceite is with the Puerta de la Macarena and Puerta de Córdoba the only three access preserved in today of those who had the walls of Seville, Andalusia, Spain.

The Puerta de Triana was the generic name for an Almohad gate and a Christian gate rose in the same place. It was one of the gates of the walled enclosure of Seville (Andalusia).

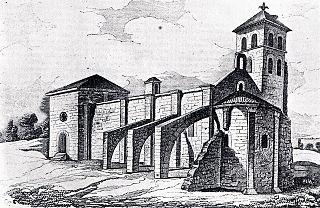

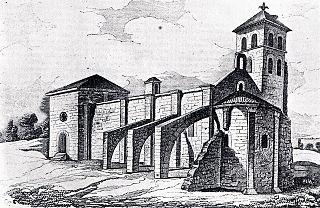

The Iglesia de Santa María del Temple was a Romanesque church located in the town of Ceinos de Campos, in Castile and León (Spain).

The Alarcones Gate is a city gate located in the city of Toledo, in Castile-La Mancha, Spain. It is also known by the name of Puerta de Moaguía, as cited in Mozarabic documents of 1216; and Puerta Alta de la Herrería, because it is located at the end of the street where workshops dedicated to ironworks were located.

Old Town of Cáceres is a historic walled city in Cáceres, Spain.

The Walls of Cuéllar are Romanesque defensive walls that surrounds the old town of the Segovian village of Cuéllar. They represent one of the most important and best preserved walled complexes in the autonomous community of Castile and León (Spain).

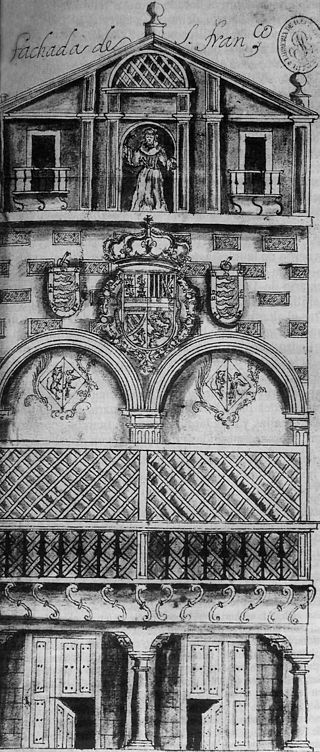

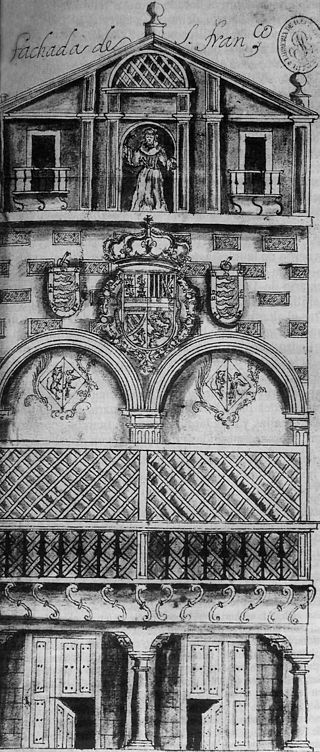

The Convent of St. Francis, in Valladolid, Spain, was founded in the 13th century and located outside the city walls, in front of the market square. The convent was protected and sponsored in that century by Doña Violante, wife of King Alfonso X the Wise. Its existence had a great impact on the social and religious life of Valladolid, extending its life until 1836, when it was demolished and its huge plot of land was divided up and put up for sale. From that date, it became part of the lost patrimony of Valladolid.