Related Research Articles

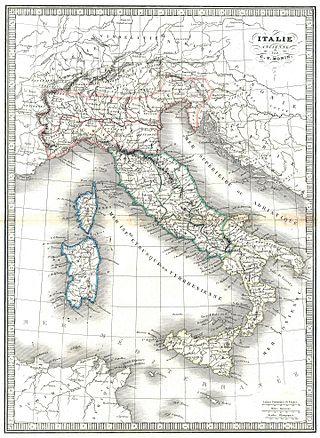

The history of the Jews in Italy spans more than two thousand years to the present. The Jewish presence in Italy dates to the pre-Christian Roman period and has continued, despite periods of extreme persecution and expulsions, until the present. As of 2019, the estimated core Jewish population in Italy numbers around 45,000.

Italian war crimes have mainly been associated with the Kingdom of Italy from the Italo-Turkish War then to Pacification of Libya, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II.

The Kraków Ghetto was one of five major metropolitan Nazi ghettos created by Germany in the new General Government territory during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It was established for the purpose of exploitation, terror, and persecution of local Polish Jews. The ghetto was later used as a staging area for separating the "able workers" from those to be deported to extermination camps in Operation Reinhard. The ghetto was liquidated between June 1942 and March 1943, with most of its inhabitants deported to the Belzec extermination camp as well as to Płaszów slave-labor camp, and Auschwitz concentration camp, 60 kilometres (37 mi) rail distance.

Beginning with the invasion of Poland during World War II, the Nazi regime set up ghettos across German-occupied Eastern Europe in order to segregate and confine Jews, and sometimes Romani people, into small sections of towns and cities furthering their exploitation. In German documents, and signage at ghetto entrances, the Nazis usually referred to them as Jüdischer Wohnbezirk or Wohngebiet der Juden, both of which translate as the Jewish Quarter. There were several distinct types including open ghettos, closed ghettos, work, transit, and destruction ghettos, as defined by the Holocaust historians. In a number of cases, they were the place of Jewish underground resistance against the German occupation, known collectively as the ghetto uprisings.

The Lwów Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto in the city of Lwów in the territory of Nazi-administered General Government in German-occupied Poland.

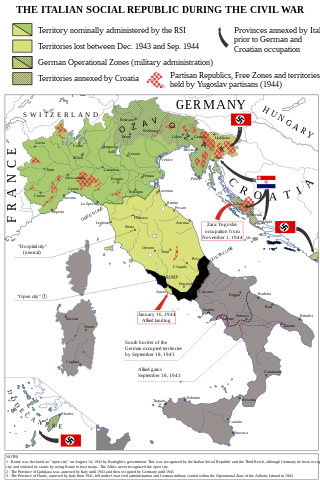

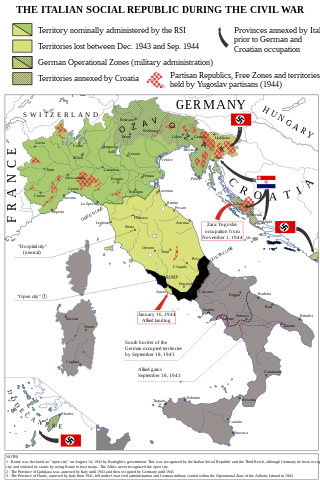

The Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills was a Nazi German occupation zone in the sub-Alpine area in Italy during World War II.

Holocaust trains were railway transports run by the Deutsche Reichsbahn and other European railways under the control of Nazi Germany and its allies, for the purpose of forcible deportation of the Jews, as well as other victims of the Holocaust, to the Nazi concentration, forced labour, and extermination camps.

The Congress of Verona in November 1943 was the only congress of the Italian Republican Fascist Party, the successor of the National Fascist Party. At the time, the Republican Fascist Party was nominally in charge of the Italian Social Republic, also called the Salò Republic, which was a fascist state set up in Northern Italy after the Italian government signed an armistice with the Allies and fled to Southern Italy. The Salò Republic was in fact a German puppet state and most of its internal and external policies were dictated by German military commanders. Nevertheless, Italian fascists were allowed to keep the trappings of sovereignty. It was under these conditions that they organized the Congress of Verona, ostensibly for the purpose of charting a new political course and rejuvenating the Italian fascist movement. The attitude of the Italian Fascists towards Italian Jews also drastically changed after the Congress of Verona, when Fascist authorities declared them to be of "enemy nationality" and begun to actively participate in the prosecution and arrest of Jews.

The Będzin Ghetto was a World War II ghetto set up by Nazi Germany for the Polish Jews in the town of Będzin in occupied south-western Poland. The formation of the 'Jewish Quarter' was pronounced by the German authorities in July 1940. Over 20,000 local Jews from Będzin, along with additional 10,000 Jews expelled from neighbouring communities, were forced to subsist there until the end of the ghetto history during the Holocaust. Most of the able-bodied poor were forced to work in German military factories before being transported aboard Holocaust trains to the nearby concentration camp at Auschwitz where they were exterminated. The last major deportation of the ghetto inmates by the German SS – men, women and children – between 1 and 3 August 1943 was marked by the ghetto uprising by members of the Jewish Combat Organization.

The Radom Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto set up in March 1941 in the city of Radom during the Nazi occupation of Poland, for the purpose of persecution and exploitation of Polish Jews. It was closed off from the outside officially in April 1941. A year and a half later, the liquidation of the ghetto began in August 1942, and ended in July 1944, with approximately 30,000–32,000 victims deported aboard Holocaust trains to their deaths at the Treblinka extermination camp.

The Fossoli camp was a concentration camp in Italy, established during World War II and located in the village Fossoli, Carpi, Emilia-Romagna. It began as a prisoner of war camp in 1942, later being a Jewish concentration camp, then a police and transit camp, a labour collection centre for Germany and, finally, a refugee camp, before closing in 1970.

The Holocaust in Bulgaria was the persecution of Jews between 1941 and 1944 in the Tsardom of Bulgaria and their deportation and annihilation in the Bulgarian-occupied regions of Yugoslavia and Greece during World War II, arranged by the Nazi Germany-allied government of Tsar Boris III and prime minister Bogdan Filov. The persecution began in 1941 with the passing of anti-Jewish legislation and culminated in March 1943 with the detention and deportation of almost all – 11,343 – of the Jews living in Bulgarian-occupied regions of Northern Greece, Yugoslav Macedonia and Pirot. These were deported by the Bulgarian authorities to Vienna and ultimately sent to extermination camps in Nazi-occupied Poland.

The Holocaust in Italy was the persecution, deportation, and murder of Jews between 1943 and 1945 in the Italian Social Republic, the part of the Kingdom of Italy occupied by Nazi Germany after the Italian surrender on 8 September 1943, during World War II.

The raid on the Roman Ghetto took place on 16 October 1943. A total of 1,259 people, mainly members of the Jewish community—numbering 363 men, 689 women, and 207 children—were detained by the Gestapo. Of these detainees, 1,023 were identified as Jews and deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Of these deportees, only fifteen men and one woman survived.

Two of the three major Axis powers of World War II—Nazi Germany and their Fascist Italian allies—committed war crimes in the Kingdom of Italy.

Karl Friedrich Titho was a Germany military officer, who as commander of the Fossoli di Carpi and Bolzano Transit Camps oversaw the Cibeno Massacre in 1944. Titho was jailed in the Netherlands after World War II for other war crimes committed there, released in 1953, and then deported to Germany. Despite an arrest warrant in Italy in 1954, Titho was never extradited to stand trial for his actions in Italy, and died in Germany in 2001, confessing and repenting his role in the atrocities just days before his death.

Friedrich Boßhammer (1906–1972) was a German jurist, SS-Sturmbannführer and close associate of Adolf Eichmann, responsible for the deportation of the Italian Jews to extermination camps from January 1944 until the end of the war in Europe. He was arrested in West Germany in 1968 and stood trial. Boßhammer was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in April 1972 for his involvement in the deportation of 3,300 Jews from Italy, but died before he could serve time in prison.

Karl Brunner was a German lawyer, SS-Brigadeführer and Generalmajor of the police and the SS and police leader in Salzburg and Bolzano. Brunner served as head of the Einsatzkommando 4/I during the invasion of Poland and the early stages of the German occupation in 1939, tasked with the killing of Polish civilians. During his time in Northern Italy he was also responsible for the arrest, and ultimately, the deportation of the Jews in his area of jurisdiction, as well as reprisals against Italian civilians.

From 4 to 7 November 1938, thousands of Jews were deported from Slovakia to the no-man's land on the Slovak−Hungarian border. Following Hungarian territorial gains in the First Vienna Award on 2 November, Slovak Jews were accused of favoring Hungary in the dispute. With the help of Adolf Eichmann, Slovak People's Party leaders planned the deportation, which was carried out by local police and the Hlinka Guard. Conflicting orders were issued to target either Jews who were poor or those who lacked Slovak citizenship, resulting in chaos.

References

- ↑ Gentile 2005, p. 10.

- ↑ Philip Morgan (10 November 2003). Italian Fascism, 1915-1945. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-230-80267-4.

- ↑ Vitello, Paul (4 November 2010). "Scholars Reconsidering Italy's Treatment of Jews in the Nazi Era". New York Times . Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 Megargee 2012, p. 392.

- 1 2 Gentile 2005, p. 15.

- 1 2 Joshua D. Zimmerman (27 June 2005). Jews in Italy Under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922-1945. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521841016 . Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ↑ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; White, Joseph R. (29 May 2018). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253023865 . Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Ordine di internare tutti gli ebrei, a qualunque nazionalità appartengano. Ordinanza di polizia RSI n.5 del 30 novembre 1943" [Order to intern all Jews, whatever nationality they belong to. RSI Police Order No. 5 from 30 November 1943]. campifascisti.it (in Italian). Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ Peter Egill Brownfeld (2003). "The Italian Holocaust: The Story of an Assimilated Jewish Community". American Council for Judaism . Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Megargee 2012, p. 428.

- ↑ Bridget Kevane (29 June 2011). "A Wall of Indifference: Italy's Shoah Memorial". The Jewish Daily Forward.com. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "The "Final Solution": Estimated Number of Jews Killed". Jewish Virtual Library . Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ "Italy". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum . Retrieved 25 September 2018.

Bibliography

- Gentile, Carlo (October 2005). The Police Transit Camps in Fossoli and Bolzano - Historical report in connection with the trial of Manfred Seifert (Report). Cologne.

- Megargee, Geoffrey P., ed. (2012). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945 - Volume III - Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. in association with United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02373-5.