Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to ancient Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described in his textbook on geometry, Elements. Euclid's approach consists in assuming a small set of intuitively appealing axioms (postulates) and deducing many other propositions (theorems) from these. Although many of Euclid's results had been stated earlier, Euclid was the first to organize these propositions into a logical system in which each result is proved from axioms and previously proved theorems.

In mathematics, two quantities are in the golden ratio if their ratio is the same as the ratio of their sum to the larger of the two quantities. Expressed algebraically, for quantities and with , is in a golden ratio to if

A triangle is a polygon with three corners and three sides, one of the basic shapes in geometry. The corners, also called vertices, are zero-dimensional points while the sides connecting them, also called edges, are one-dimensional line segments. A triangle has three internal angles, each one bounded by a pair of adjacent edges; the sum of angles of a triangle always equals a straight angle. The triangle is a plane figure and its interior is a planar region. Sometimes an arbitrary edge is chosen to be the base, in which case the opposite vertex is called the apex; the shortest segment between the base and apex is the height. The area of a triangle equals one-half the product of height and base length.

In Euclidean geometry, two objects are similar if they have the same shape, or if one has the same shape as the mirror image of the other. More precisely, one can be obtained from the other by uniformly scaling, possibly with additional translation, rotation and reflection. This means that either object can be rescaled, repositioned, and reflected, so as to coincide precisely with the other object. If two objects are similar, each is congruent to the result of a particular uniform scaling of the other.

In Euclidean plane geometry, a rectangle is a rectilinear convex polygon or a quadrilateral with four right angles. It can also be defined as: an equiangular quadrilateral, since equiangular means that all of its angles are equal ; or a parallelogram containing a right angle. A rectangle with four sides of equal length is a square. The term "oblong" is used to refer to a non-square rectangle. A rectangle with vertices ABCD would be denoted as ABCD.

In geometry and trigonometry, a right angle is an angle of exactly 90 degrees or /2 radians corresponding to a quarter turn. If a ray is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the adjacent angles are equal, then they are right angles. The term is a calque of Latin angulus rectus; here rectus means "upright", referring to the vertical perpendicular to a horizontal base line.

In geometry, a trapezoid in North American English, or trapezium in British English, is a quadrilateral that has one pair of parallel sides.

In geometry, a golden rectangle is a rectangle with side lengths in golden ratio or with approximately equal to 1.618 or 89/55.

Graph paper, coordinate paper, grid paper, or squared paper is writing paper that is printed with fine lines making up a regular grid. It is available either as loose leaf paper or bound in notebooks or Graph Books.

Descriptive geometry is the branch of geometry which allows the representation of three-dimensional objects in two dimensions by using a specific set of procedures. The resulting techniques are important for engineering, architecture, design and in art. The theoretical basis for descriptive geometry is provided by planar geometric projections. The earliest known publication on the technique was "Underweysung der Messung mit dem Zirckel und Richtscheyt", published in Linien, Nuremberg: 1525, by Albrecht Dürer. Italian architect Guarino Guarini was also a pioneer of projective and descriptive geometry, as is clear from his Placita Philosophica (1665), Euclides Adauctus (1671) and Architettura Civile, anticipating the work of Gaspard Monge (1746–1818), who is usually credited with the invention of descriptive geometry. Gaspard Monge is usually considered the "father of descriptive geometry" due to his developments in geometric problem solving. His first discoveries were in 1765 while he was working as a draftsman for military fortifications, although his findings were published later on.

A cylinder has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

The rule of thirds is a rule of thumb for composing visual art such as designs, films, paintings, and photographs. The guideline proposes that an image should be imagined as divided into nine equal parts by two equally spaced horizontal lines and two equally spaced vertical lines, and that important compositional elements should be placed along these lines or their intersections. Aligning a subject with these points creates more tension, energy and interest in the composition than simply centering the subject.

The term composition means "putting together". It can be thought of as the organization of the elements of art according to the principles of art. Composition can apply to any work of art, from music through writing and into photography, that is arranged using conscious thought.

Jay Hambidge (1867–1924) was an American artist who formulated the theory of "dynamic symmetry", a system defining compositional rules, which was adopted by several notable American and Canadian artists in the early 20th century.

In Euclidean geometry, the British flag theorem says that if a point P is chosen inside a rectangle ABCD then the sum of the squares of the Euclidean distances from P to two opposite corners of the rectangle equals the sum to the other two opposite corners. As an equation:

A dynamic rectangle is a right-angled, four-sided figure with dynamic symmetry which, in this case, means that aspect ratio is a distinguished value in dynamic symmetry, a proportioning system and natural design methodology described in Jay Hambidge's books. These dynamic rectangles begin with a square, which is extended to form the desired figure, which can be the golden rectangle, the 2:3 rectangle, the double square (1:2), or a root rectangle.

Mathematics and art are related in a variety of ways. Mathematics has itself been described as an art motivated by beauty. Mathematics can be discerned in arts such as music, dance, painting, architecture, sculpture, and textiles. This article focuses, however, on mathematics in the visual arts.

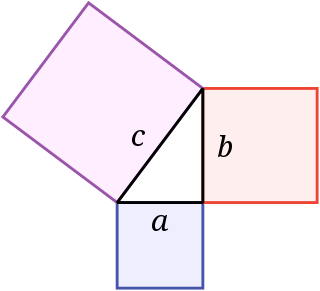

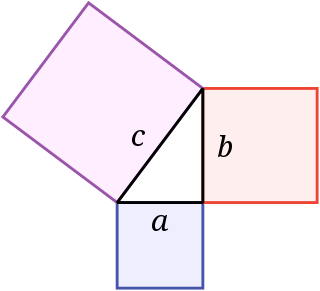

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras' theorem is a fundamental relation in Euclidean geometry between the three sides of a right triangle. It states that the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares on the other two sides.

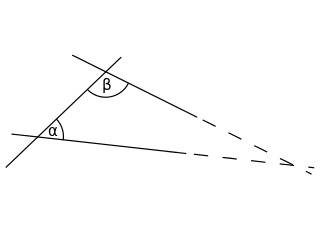

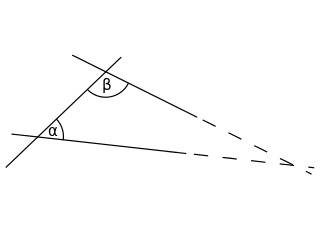

In geometry, the parallel postulate, also called Euclid's fifth postulate because it is the fifth postulate in Euclid's Elements, is a distinctive axiom in Euclidean geometry. It states that, in two-dimensional geometry:

If a line segment intersects two straight lines forming two interior angles on the same side that are less than two right angles, then the two lines, if extended indefinitely, meet on that side on which the angles sum to less than two right angles.