Related Research Articles

Quinoa is a flowering plant in the amaranth family. It is an herbaceous annual plant grown as a crop primarily for its edible seeds; the seeds are rich in protein, dietary fiber, B vitamins and dietary minerals in amounts greater than in many grains. Quinoa is not a grass but rather a pseudocereal botanically related to spinach and amaranth, and originated in the Andean region of northwestern South America. It was first used to feed livestock 5,200–7,000 years ago, and for human consumption 3,000–4,000 years ago in the Lake Titicaca basin of Peru and Bolivia.

The Aymara or Aimara people are an indigenous people in the Andes and Altiplano regions of South America; about 2.3 million live in northwest Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. Their ancestors lived in the region for many centuries before becoming a subject people of the Inca in the late 15th or early 16th century, and later of the Spanish in the 16th century. With the Spanish American wars of independence (1810–1825), the Aymaras became subjects of the new nations of Bolivia and Peru. After the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), Chile annexed territory with Aymara population.

Chinampa is a technique used in Mesoamerican agriculture which relies on small, rectangular areas of fertile arable land to grow crops on the shallow lake beds in the Valley of Mexico. They are built up on wetlands of a lake or freshwater swamp for agricultural purposes, and their proportions ensure optimal moisture retention. The United Nations designated it a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System in 2018. The Aztecs created the very first chinampa.

Beni, sometimes El Beni, is a northeastern department of Bolivia, in the lowlands region of the country. It is the second-largest department in the country, covering 213,564 square kilometers, and it was created by supreme decree on November 18, 1842, during the administration of General José Ballivián. Its capital is Trinidad.

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to most of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. In the pre-Columbian era, many societies flourished in Mesoamerica for more than 3,000 years before the Spanish colonization of the Americas begun at Hispaniola island in 1493. In world history, Mesoamerica was the site of two historical transformations: (i) primary urban generation, and (ii) the formation of New World cultures from the mixtures of the indigenous Mesoamerican peoples with the European, African, and Asian peoples who were introduced by the Spanish colonization of the Americas.

The geography of Mesoamerica describes the geographic features of Mesoamerica, a culture area in the Americas inhabited by complex indigenous pre-Columbian cultures exhibiting a suite of shared and common cultural characteristics. Several well-known Mesoamerican cultures include the Olmec, Teotihuacan, the Maya, the Aztec and the Purépecha. Mesoamerica is often subdivided in a number of ways. One common method, albeit a broad and general classification, is to distinguish between the highlands and lowlands. Another way is to subdivide the region into sub-areas that generally correlate to either culture areas or specific physiographic regions.

Ancient Maya cuisine was varied and extensive. Many different types of resources were consumed, including maritime, flora, and faunal material, and food was obtained or produced through strategies such as hunting, foraging, and large-scale agricultural production. Plant domestication concentrated upon several core foods, the most important of which was maize.

Incan agriculture was the culmination of thousands of years of farming and herding in the high-elevation Andes mountains of South America, the coastal deserts, and the rainforests of the Amazon basin. These three radically different environments were all part of the Inca Empire and required different technologies for agriculture. Inca agriculture was also characterized by the variety of crops grown, the lack of a market system and money, and the unique mechanisms by which the Incas organized their society. Andean civilization was "pristine"—one of six civilizations worldwide which were indigenous and not derivative from other civilizations. Most Andean crops and domestic animals were likewise pristine—not known to other civilizations. Potatoes, tomatoes, chile peppers, and quinoa were among the many unique crops; Camelids and guinea pigs were the unique domesticated animals.

Waru Waru is an Aymara term for the agricultural technique developed by pre-Hispanic people in the Andes region of South America from Ecuador to Bolivia; this regional agricultural technique is also referred to as camellones in Spanish. Functionally similar agricultural techniques have been developed in other parts of the world, all of which fall under the broad category of raised field agriculture.

Chitemene, from the ciBemba word meaning “place where branches have been cut for a garden”, is a system of slash and burn agriculture practiced throughout northern Zambia. It involves coppicing or pollarding of standing trees in a primary or secondary growth Miombo woodland, stacking of the cut biomass, and eventual burning of the cut biomass in order to create a thicker layer of ash than would be possible with in situ burning. Crops such as maize, finger millet, sorghum, or cassava are then planted in the burned area.

The Lupaca, Lupaka, or Lupaqa people were one of the divisions of the ancestral Aymaras. The Lupaca lived for many centuries near Lake Titicaca in Peru and their lands possibly extended into Bolivia. The Lupacas and other Aymara peoples formed powerful kingdoms after the collapse of the Tiwanaku Empire in the 11th century. In the mid 15th century they were conquered by the Inca Empire and in the 1530s came under the control of the Spanish Empire.

The Andean civilizations were South American complex societies of many indigenous people. They stretched down the spine of the Andes for 4,000 km (2,500 mi) from southern Colombia, to Ecuador and Peru, including the deserts of coastal Peru, to north Chile and northwest Argentina. Archaeologists believe that Andean civilizations first developed on the narrow coastal plain of the Pacific Ocean. The Caral or Norte Chico civilization of coastal Peru is the oldest known civilization in the Americas, dating back to 3500 BCE. Andean civilization is one of the six "pristine" civilizations of the world, created independently and without influence by other civilizations.

William Maxfield Denevan is an American geographer. He is professor emeritus of Geography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is a prominent member of the Berkeley School of cultural-historical geography. He also worked in the Latin American Center and the Institute for Environmental Studies at Wisconsin. His research interests are in the historical ecology of the Americas, especially Amazonia and the Andes.

Bolivians are people identified with the country of Bolivia. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Bolivians, several of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being Bolivian.

The Otavalos are an indigenous people native to the Andean mountains of Imbabura Province in northern Ecuador. The Otavalos also inhabit the city of Otavalo in that province. Commerce and handcrafts are among the principal economic activities of the Otavalos, who enjoy a higher standard of living than most indigenous groups in Ecuador and many mestizos of their area.

The Tiwanaku Polity was a Pre-Columbian polity in western Bolivia based in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. Tiwanaku was one of the most significant Andean civilizations. Its influence extended into present-day Peru and Chile and lasted from around 600 to 1000 AD. Its capital was the monumental city of Tiwanaku, located at the center of the polity's core area in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. This area has clear evidence for large-scale agricultural production on raised fields that probably supported the urban population of the capital. Researchers debate whether these fields were administered by a bureaucratic state (top-down) or through a federation of communities with local autonomy. Tiwanaku was once thought to be an expansive military empire, based mostly on comparisons to the later Inca Empire. However, recent research suggests that labelling Tiwanaku as an empire or even different varieties of a state may even be misleading. Tiwanaku is missing a number of features used to define these types of polities: there is no defensive architecture at any Tiwanaku site or changes in weapon technology, there are no princely burials or other evidence of a ruling dynasty or a formal social hierarchy, no evidence of state-maintained roads or outposts, and no markets.

Pre-Columbian Bolivia covers the historical period between 10,000 BCE, when the Upper Andes region was first populated and 1532, when Spanish conquistadors invaded Inca empire. The Andes region of Pre-Columbian South America was dominated by the Tiwanaku civilization until about 1200, when the regional kingdoms of the Aymara emerged as the most powerful of the ethnic groups living in the densely populated region surrounding Lake Titicaca. Power struggles continued until 1450, when the Incas incorporated upper Bolivia into their growing empire. Based in present-day Peru, the Incas instituted agricultural and mining practices that rivaled those put in place many years later by European conquerors. They also established a strong military force, and centralized political power. Despite their best efforts however, the Incas never completely controlled the nomadic tribes of the Bolivian lowlands, nor did they fully assimilate the Aymara kingdoms into their society. These internal divisions doomed the Inca Empire when European conquerors arrived.

The Llanos de Moxos, also known as the Llanos de Mojos and the Beni Savanna, have extensive remains of pre-Columbian agricultural societies scattered over most of Beni Department, Bolivia. The remains testify to a well-organized and numerous indigenous people. This contradicts the traditional view of archaeologists, notably Betty Meggers, who asserted that the Amazon River Basin was not environmentally able to sustain a large population and that its indigenous inhabitants were hunter-gatherer bands or slash-and-burn farmers. In the 1960s, petroleum company geologists and geographer William Denevan were among the first to publicize the existence of extensive prehistoric earthworks constructed in the Amazon, especially in the Llanos de Moxos.

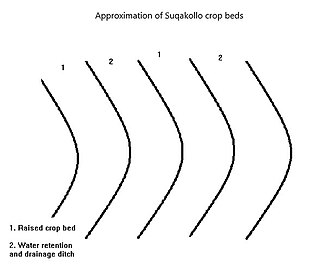

Suqakollos are elevated crop fields designed to promote water conservation in agriculture. Originating in the highlands of the Puno Region in Peru, Suqakollo fields were implemented by indigenous Andeans to supply food crops with water through the creation of specialized stepwells.

Agriculture in Chile has a long history dating back to the Pre-Hispanic period. Indigenous peoples practised varying types of agriculture, from the oases of the Atacama Desert to as far south as the Guaitecas Archipelago. Potato was the staple food in the populous Mapuche lands. Llama and chilihueque herding was practised by various indigenous groups.

[Chile] is rich in pastures and cultivated fields, in which all kind of animals and plants can be breed or grown, there is plenty of very beautiful wood for making houses, and plenty of firewood, and rich gold mines, and all land is full of them...

References

- ↑ What is Raised Field Agriculture?

- ↑ Dillehay, Tom D.; Pino Quivira, Mario; Bonzani, Renée; Silva, Claudia; Wallner, Johannes; Le Quesne, Carlos (2007) Cultivated wetlands and emerging complexity in south-central Chile and long distance effects of climate change. Antiquity 81 (2007): 949–960