The geography of Bolivia includes the Eastern Andes Mountain Range which bisects Bolivia roughly from north to south. To the east of that mountain chain are lowland plains of the Amazon Basin, and to the west is the Altiplano which is a highland plateau where Lake Titicaca is located. Bolivia's geography has features similar to those of Peru which abuts Bolivia's northwest border; like Bolivia, Peru is bisected from north to south by the Eastern Andes Mountains, and these two countries share Lake Titicaca which is the highest navigable lake on Earth. Unlike Peru, however, Bolivia is one of the two landlocked countries in South America, the other being Paraguay which is located along Bolivia's southeast border.

Lake Titicaca is a large freshwater lake in the Andes mountains on the border of Bolivia and Peru. It is often called the highest navigable lake in the world. By both the volume of water and surface area, Titicaca is the largest lake in South America.

Tiwanaku is a Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia, near Lake Titicaca, about 70 kilometers from La Paz, and it is one of the largest sites in South America. Surface remains currently cover around 4 square kilometers and include decorated ceramics, monumental structures, and megalithic blocks. The site's population probably peaked around AD 800 with 10,000 to 20,000 people.

The Aymara or Aimara, people are an indigenous people in the Andes and Altiplano regions of South America; about 2.3 million live in northwest Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. Their ancestors lived in the region for many centuries before becoming a subject people of the Inca in the late 15th or early 16th century, and later of the Spanish in the 16th century. With the Spanish-American wars of independence (1810–1825), the Aymaras became subjects of the new nations of Bolivia and Peru. After the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), Chile annexed territory with the Aymara population.

The Altiplano, Collao or Andean Plateau, in west-central South America, is the most extensive high plateau on Earth outside Tibet. The plateau is located at the latitude of the widest part of the north–south-trending Andes. The bulk of the Altiplano lies in Bolivia, but its northern parts lie in Peru, and its southwestern fringes lie in Chile.

Lake Poopó was a large saline lake in a shallow depression in the Altiplano Mountains in Oruro Department, Bolivia, at an altitude of approximately 3,700 m (12,100 ft). Due to the lake's length and width, it made up the eastern half of Oruro, known as a mining region in southwest Bolivia. The permanent part of the lake body covered approximately 1,000 square kilometres (390 sq mi) and it was the second-largest lake in the country. The lake received most of its water from the Desaguadero River, which flows from Lake Titicaca at the north end of the Altiplano. Since the lake lacked any major outlet and had a mean depth of less than 3 m (10 ft), the surface area differed greatly seasonally.

Capinota is a small town in the Bolivian Department of Cochabamba and capital of the Capinota Province.

An andén, Spanish for "platform", is a stair-step like terrace dug into the slope of a hillside for agricultural purposes. The term is most often used to refer to the terraces built by pre-Columbian cultures in the Andes mountains of South America. Andenes had several functions, the most important of which was to increase the amount of cultivatable land available to farmers by leveling a planting area for crops. The best known andenes are in Peru, especially in the Sacred Valley near the Inca capital of Cuzco and in the Colca Canyon. Many andenes have survived for more than 500 years and are still in use by farmers throughout the region.

Incan agriculture was the culmination of thousands of years of farming and herding in the high-elevation Andes mountains of South America, the coastal deserts, and the rainforests of the Amazon basin. These three radically different environments were all part of the Inca Empire and required different technologies for agriculture. Inca agriculture was also characterized by the variety of crops grown, the lack of a market system and money, and the unique mechanisms by which the Incas organized their society. Andean civilization was "pristine"—one of six civilizations worldwide which were indigenous and not derivative from other civilizations. Most Andean crops and domestic animals were likewise pristine—not known to other civilizations. Potatoes, tomatoes, chile peppers, and quinoa were among the many unique crops; Camelids and guinea pigs were the unique domesticated animals.

The role of agriculture in the Bolivian economy in the late 1980s expanded as the collapse of the tin industry forced the country to diversify its productive and export base. Agricultural production as a share of GDP was approximately 23 percent in 1987, compared with 30 percent in 1960 and a low of just under 17 percent in 1979. The recession of the 1980s, along with unfavorable weather conditions, particularly droughts and floods, hampered output. Agriculture employed about 46 percent of the country's labor force in 1987. Most production, with the exception of coca, focused on the domestic market and self-sufficiency in food. Agricultural exports accounted for only about 15 percent of total exports in the late 1980s, depending on weather conditions and commodity prices for agricultural goods, hydrocarbons, and minerals.

The Lupaca, Lupaka, or Lupaqa people were one of the divisions of the ancestral Aymaras. The Lupaca lived for many centuries near Lake Titicaca in Peru and their lands possibly extended into Bolivia. The Lupacas and other Aymara peoples formed powerful kingdoms after the collapse of the Tiwanaku Empire in the 11th century. In the mid 15th century they were conquered by the Inca Empire and in the 1530s came under the control of the Spanish Empire.

The Andean civilizations were South American complex societies of many indigenous people. They stretched down the spine of the Andes for 4,000 km (2,500 mi) from southern Colombia, to Ecuador and Peru, including the deserts of coastal Peru, to north Chile and northwest Argentina. Archaeologists believe that Andean civilizations first developed on the narrow coastal plain of the Pacific Ocean. The Caral or Norte Chico civilization of coastal Peru is the oldest known civilization in the Americas, dating back to 3500 BCE. Andean civilization is one of the six "pristine" civilizations of the world, created independently and without influence by other civilizations.

Indigenous horticulture is practised in various ways across all inhabited continents. Indigenous refers to the native peoples of a given area and horticulture is the practice of small-scale intercropping.

The vertical archipelago is a term coined by sociologist and anthropologist John Victor Murra under the influence of economist Karl Polanyi to describe the native Andean agricultural economic model of accessing and distributing resources. While some cultures developed market economies, the predominant models were systems of barter and shared labor. These reached their greatest development under the Inca Empire. Scholars have identified four distinct ecozones, at different elevations.

The agricultural practices of the Native Americans inhabiting the American Southwest, which includes the states of Arizona and New Mexico plus portions of surrounding states and neighboring Mexico, are influenced by the low levels of precipitation in the region. Irrigation and several techniques of water harvesting and conservation were essential for successful agriculture. To take advantage of limited water, the southwestern Native Americans utilized irrigation canals, terraces (trincheras), rock mulches, and floodplain cultivation. Success in agriculture enabled some Native Americans to live in communities which numbered in the thousands as compared to their former lives as hunter-gatherers in which their bands numbered only a few dozen.

In agriculture, a raised field is a large, cultivated elevation, typically bounded by water-filled ditches, that is used to allow cultivators to control environmental factors such as moisture levels, frost damage, and flooding. Examples of raised field agriculture can be found among some Pre-Hispanic cultures of Latin America, such as those from tropical lowlands and the Budi Lake Mapuche.

The Tiwanaku Polity was a Pre-Columbian polity in western Bolivia based in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. Tiwanaku was one of the most significant Andean civilizations. Its influence extended into present-day Peru and Chile and lasted from around 600 to 1000 AD. Its capital was the monumental city of Tiwanaku, located at the center of the polity's core area in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. This area has clear evidence for large-scale agricultural production on raised fields that probably supported the urban population of the capital. Researchers debate whether these fields were administered by a bureaucratic state (top-down) or through a federation of communities with local autonomy. Tiwanaku was once thought to be an expansive military empire, based mostly on comparisons to the later Inca Empire. However, recent research suggests that labelling Tiwanaku as an empire or even different varieties of a state may even be misleading. Tiwanaku is missing a number of features used to define these types of polities: there is no defensive architecture at any Tiwanaku site or changes in weapon technology, there are no princely burials or other evidence of a ruling dynasty or a formal social hierarchy, no evidence of state-maintained roads or outposts, and no markets.

Pre-Columbian Bolivia covers the historical period between 10,000 BCE, when the Upper Andes region was first populated and 1532, when Spanish conquistadors invaded Inca empire. The Andes region of Pre-Columbian South America was dominated by the Tiwanaku civilization until about 1200, when the regional kingdoms of the Aymara emerged as the most powerful of the ethnic groups living in the densely populated region surrounding Lake Titicaca. Power struggles continued until 1450, when the Incas incorporated upper Bolivia into their growing empire. Based in present-day Peru, the Incas instituted agricultural and mining practices that rivaled those put in place many years later by European conquerors. They also established a strong military force, and centralized political power. Despite their best efforts however, the Incas never completely controlled the nomadic tribes of the Bolivian lowlands, nor did they fully assimilate the Aymara kingdoms into their society. These internal divisions doomed the Inca Empire when European conquerors arrived.

The Llanos de Moxos, also known as the Llanos de Mojos and the Beni Savanna, have extensive remains of pre-Columbian agricultural societies scattered over most of Beni Department, Bolivia. The remains testify to a well-organized and numerous indigenous people. This contradicts the traditional view of archaeologists, notably Betty Meggers, who asserted that the Amazon River Basin was not environmentally able to sustain a large population and that its indigenous inhabitants were hunter-gatherer bands or slash-and-burn farmers. In the 1960s, petroleum company geologists and geographer William Denevan were among the first to publicize the existence of extensive prehistoric earthworks constructed in the Amazon, especially in the Llanos de Moxos.

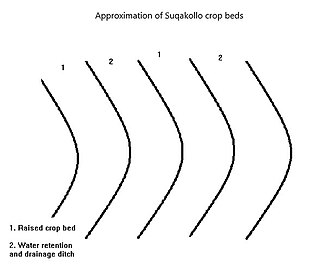

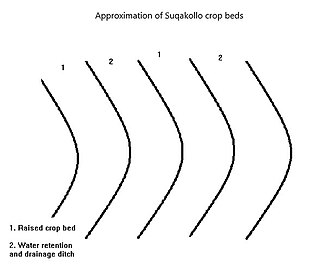

Suqakollos are elevated crop fields designed to promote water conservation in agriculture. Originating in the highlands of the Puno Region in Peru, Suqakollo fields were implemented by indigenous Andeans to supply food crops with water through the creation of specialized stepwells.