Ravenstail weaving (yeil koowu), [1] also known as Raven's Tail weaving, is a traditional form of geometric weaving-style practiced by Northwest Coast peoples. [2]

Ravenstail weaving (yeil koowu), [1] also known as Raven's Tail weaving, is a traditional form of geometric weaving-style practiced by Northwest Coast peoples. [2]

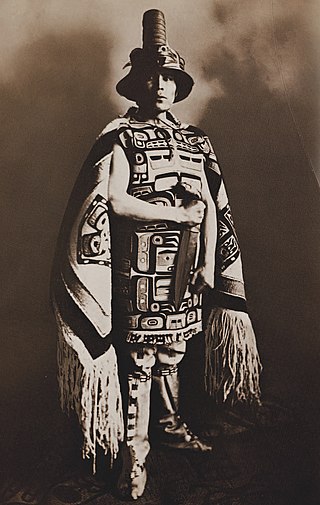

The practice of Ravenstail and Chilkat weaving originated among the Tsimshian, and was retained by traditional Tlingit and Haida weavers in present-day Alaska. [3] Ravenstail weaving is thought to be a precursor to Chilkat weaving. [2] Ravenstail weaving has sharp, geometric lines and minimal colors; while Chilkat weaving visually looks more natural with curved lines and a larger color palette. [3]

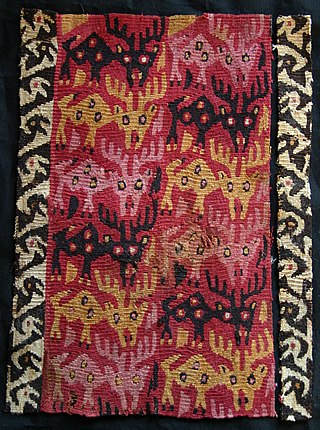

Ravenstail uses a finger-weaving technique called 'twining'. [4] Typically, for Ravenstail pieces, it is created in modern times using black and white (and sometimes yellow) colored merino sheep-wool [5] (sometimes with the traditional slender strands of animal sinew or, a more modern substitute, small amounts of silk) [6] or, when legally available and affordable to the weaver, the original traditional fiber, yarn made from wild mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) wool, [7] to create bold geometric woven patterns. [4] The early examples, ones made before first contact with foreign explorers and traders who introduced sheep's wool to the continent, were constructed from mountain goat-wool yarn. [8] There are not many surviving historical examples, with roughly a dozen Ravenstail robes in North American and European museums. [9]

After the 1800s, Ravenstail died out of popularity and due to the rise of new weaving innovations and techniques. [10] The Ravenstail weaving technique almost went extinct after 200 years of inactivity. [9] [11]

Cheryl Samuel was the first person to replicate Ravenstail weaving for revival purposes, and by the mid-1980s she had obtained permission from several Pacific Northwest indigenous tribes to revive the art to regularly teach classes on the subject. [1] In 1987, Samuel published a book The Raven's Tail: Northern Geometric Style Weaving (University of British Columbia Press). In the 1990s additional research was done to bring back the traditional craft; and museums and cultural centers in the Alaskan cities of Juneau, Ketchikan, and Sitka struggled together to revive the craft by working with both Natives and non-Natives. [9] [11] In November 1990, a Ravenstail Weaver's Guild was formed in Ketchikan through the Totem Heritage Center, and served to strengthen craft community between Native and non-Natives in the United States and Canada. [11] [1]

In 2021 the exhibition The Spirit Wraps Around You: Northern Northwest Coast Native Textiles, was held at the Alaska State Museum and included Ravenstail weaving while highlighted the oldest known weavings from Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. [12]

The Tlingit or Lingít are Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America and constitute two of the 231 federally recognized Tribes of Alaska. Most Tlingit are Alaska Natives; however, some are First Nations in Canada.

The Haida are one of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their national territories lie along the west coast of Canada and include parts of south east Alaska. Haida mythology is an indigenous religion that can be described as a nature religion, drawing on the natural world, seasonal patterns, events and objects for questions that the Haida pantheon provides explanations for. Haida mythology is also considered animistic for the breadth of the Haida pantheon in imbuing daily events with Sǥā'na qeda's.

Louis Situwuka Shotridge was an American art collector and ethnological assistant who was an expert on the traditions of his people, the Tlingit nation of southeastern Alaska. His Tlingit name was Stoowukháa, which means "Astute One."

Northwest Coast art is the term commonly applied to a style of art created primarily by artists from Tlingit, Haida, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka'wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth and other First Nations and Native American tribes of the Northwest Coast of North America, from pre-European-contact times up to the present.

Delores E. Churchill is a Native American artist of Haida descent. She is a weaver of baskets, hats, robes, and other regalia, as well as leading revitalization efforts for Haida, her native language.

Chilkat weaving is a traditional form of weaving practiced by Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and other Northwest Coast peoples of Alaska and British Columbia. Chilkat robes are worn by high-ranking tribal members on civic or ceremonial occasions, including dances. The blankets are almost always black, white, yellow and blue.

Jennie Thlunaut was a Tlingit artist, who is credited with keeping the art of Chilkat weaving alive and was one of the most celebrated Northwest Coastal master weavers of the 20th century.

The textile arts of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas are decorative, utilitarian, ceremonial, or conceptual artworks made from plant, animal, or synthetic fibers by Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

The Totem Heritage Center is a historical and cultural museum founded in 1976 and located in Ketchikan, Alaska. The center is operated by the city of Ketchikan.

Teri Rofkar, or Chas' Koowu Tla'a (1956–2016), was a Tlingit weaver and educator from Sitka, Alaska. She specialized in Ravenstail designs and spruce root baskets.

Chilkat or The Chilkat, or Chilkats, may refer to:

Clarissa Rizal was a Tlingit artist of Filipino descent. She was best known as a Chilkat and Ravenstail weaver, but she also worked in painting, printmaking, carving, and sculpting.

Lily Hope is an Alaska Native artist, designer, teacher, weaver, Financial Freedom planner, and community facilitator. She is primarily known for her skills at weaving customary Northwest Coast ceremonial regalia such as Chilkat robes and ensembles. She owns a public-facing studio in Juneau, called Wooshkindein Da.àat: Lily Hope Weaver Studio which opened downtown in 2022. Lily Hope is a mother of five children, and works six days a week.

Florence Scundoo Shotridge was an Alaska Native ethnographer, museum educator, and weaver. From 1911 to 1917, she worked for the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. In 1905, she demonstrated Chilkat weaving at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon. In 1916, she co-directed with her husband Louis Shotridge a collecting expedition to Southeast Alaska that was funded by the retail magnate and Penn Museum trustee John Wanamaker.

Lani Hotch, also known as Saantaas', Sekwooneitl and Xhaatooch, is a Native American artist of Tlingit ancestry known for being a contemporary Chilkat weaver who uses Ravenstail weaving in her works.

Evelyn Vanderhoop is a Haida Nation artist from Masset, British Columbia, Canada. She paints and is a textile artist, specializing in Chilkat weaving and Raven's Tail weaving.

Vicki Lee Soboleff is a Haida and Tlingit artist, dancer, and teacher who specializes in Haida basketry. She was awarded the Margaret Nick Cooke Award in 2016 from the Alaska State Council on the Arts and the Alaska Humanities Forum for her work with Alaska Native dance.

Ursala Hudson is an Alaska Native textile artist, graphic designer, and fashion designer. She also photographs and paints. She creates Chilkat weaving, including dance regalia, belts, collars, and earrings.

Kelsey Mata is a Native American illustrator and artist. A member of the Tlingit tribe, she is known for her work in children's picture books and digital art that portray Indigenous characters and ways of life.

Nick Alan is a Native American artist and children’s book illustrator. As a member of the Tlingit tribe, he is recognized for his contributions to children's picture books that aim to revitalize the Tlingit language and strengthen cultural heritage.