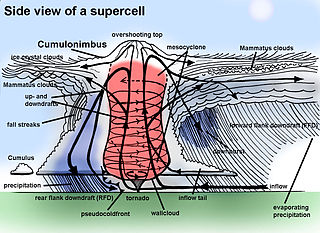

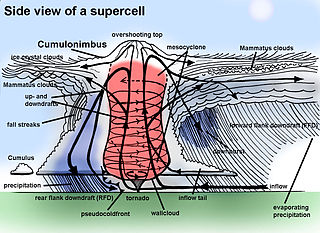

A mesocyclone is a meso-gamma mesoscale region of rotation (vortex), typically around 2 to 6 mi in diameter, most often noticed on radar within thunderstorms. In the northern hemisphere it is usually located in the right rear flank of a supercell, or often on the eastern, or leading, flank of a high-precipitation variety of supercell. The area overlaid by a mesocyclone’s circulation may be several miles (km) wide, but substantially larger than any tornado that may develop within it, and it is within mesocyclones that intense tornadoes form.

A squall is a sudden, sharp increase in wind speed lasting minutes, as opposed to a wind gust, which lasts for only seconds. They are usually associated with active weather, such as rain showers, thunderstorms, or heavy snow. Squalls refer to the increase of the sustained winds over that time interval, as there may be higher gusts during a squall event. They usually occur in a region of strong sinking air or cooling in the mid-atmosphere. These force strong localized upward motions at the leading edge of the region of cooling, which then enhances local downward motions just in its wake.

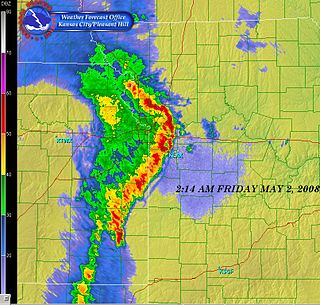

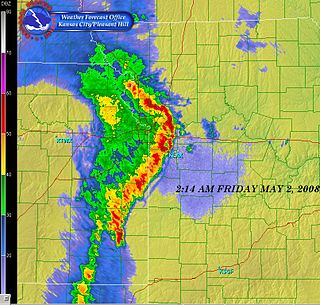

A squall line, or more accurately a quasi-linear convective system (QLCS), is a line of thunderstorms, often forming along or ahead of a cold front. In the early 20th century, the term was used as a synonym for cold front. Linear thunderstorm structures often contain heavy precipitation, hail, frequent lightning, strong straight-line winds, and occasionally tornadoes or waterspouts. Particularly strong straight-line winds can occur where the linear structure forms into the shape of a bow echo. Tornadoes can occur along waves within a line echo wave pattern (LEWP), where mesoscale low-pressure areas are present. Some bow echoes can grow to become derechos as they move swiftly across a large area. On the back edge of the rainband associated with mature squall lines, a wake low can be present, on very rare occasions associated with a heat burst.

A wall cloud is a large, localized, persistent, and often abrupt lowering of cloud that develops beneath the surrounding base of a cumulonimbus cloud and from which tornadoes sometimes form. It is typically beneath the rain-free base (RFB) portion of a thunderstorm, and indicates the area of the strongest updraft within a storm. Rotating wall clouds are an indication of a mesocyclone in a thunderstorm; most strong tornadoes form from these. Many wall clouds do rotate; however, some do not.

A derecho is a widespread, long-lived, straight-line wind storm that is associated with a fast-moving group of severe thunderstorms known as a mesoscale convective system.

A hook echo is a pendant or hook-shaped weather radar signature as part of some supercell thunderstorms. It is found in the lower portions of a storm as air and precipitation flow into a mesocyclone, resulting in a curved feature of reflectivity. The echo is produced by rain, hail, or debris being wrapped around the supercell. It is one of the classic hallmarks of tornado-producing supercells. The National Weather Service may consider the presence of a hook echo coinciding with a tornado vortex signature as sufficient to justify issuing a tornado warning.

A funnel cloud is a funnel-shaped cloud of condensed water droplets, associated with a rotating column of wind and extending from the base of a cloud but not reaching the ground or a water surface. A funnel cloud is usually visible as a cone-shaped or needle like protuberance from the main cloud base. Funnel clouds form most frequently in association with supercell thunderstorms, and are often, but not always, a visual precursor to tornadoes. Funnel clouds are visual phenomena, but these are not the vortex of wind itself.

An outflow boundary, also known as a gust front, is a storm-scale or mesoscale boundary separating thunderstorm-cooled air (outflow) from the surrounding air; similar in effect to a cold front, with passage marked by a wind shift and usually a drop in temperature and a related pressure jump. Outflow boundaries can persist for 24 hours or more after the thunderstorms that generated them dissipate, and can travel hundreds of kilometers from their area of origin. New thunderstorms often develop along outflow boundaries, especially near the point of intersection with another boundary. Outflow boundaries can be seen either as fine lines on weather radar imagery or else as arcs of low clouds on weather satellite imagery. From the ground, outflow boundaries can be co-located with the appearance of roll clouds and shelf clouds.

A bow echo is the characteristic radar return from a mesoscale convective system that is shaped like an archer's bow. These systems can produce severe straight-line winds and occasionally tornadoes, causing major damage. They can also become derechos or form Line echo wave pattern (LEWP).

Tornadogenesis is the process by which a tornado forms. There are many types of tornadoes and these vary in methods of formation. Despite ongoing scientific study and high-profile research projects such as VORTEX, tornadogenesis is a volatile process and the intricacies of many of the mechanisms of tornado formation are still poorly understood.

The rear flank downdraft (RFD) is a region of dry air wrapping around the back of a mesocyclone in a supercell thunderstorm. These areas of descending air are thought to be essential in the production of many supercellular tornadoes. Large hail within the rear flank downdraft often shows up brightly as a hook on weather radar images, producing the characteristic hook echo, which often indicates the presence of a tornado.

Outflow, in meteorology, is air that flows outwards from a storm system. It is associated with ridging, or anticyclonic flow. In the low levels of the troposphere, outflow radiates from thunderstorms in the form of a wedge of rain-cooled air, which is visible as a thin rope-like cloud on weather satellite imagery or a fine line on weather radar imagery. For observers on the ground, a thunderstorm outflow boundary often approaches in otherwise clear skies as a low, thick cloud that brings with it a gust front.

Ronald William Przybylinski was an American meteorologist who made important contributions to understanding of bow echoes, mesovortices, related quasi-linear convective system (QLCS) structures and processes, as well as QLCS related tornadoes. He also was an expert on technical aspects of weather radar and applications to both operational meteorology and research.

Convective storm detection is the meteorological observation, and short-term prediction, of deep moist convection (DMC). DMC describes atmospheric conditions producing single or clusters of large vertical extension clouds ranging from cumulus congestus to cumulonimbus, the latter producing thunderstorms associated with lightning and thunder. Those two types of clouds can produce severe weather at the surface and aloft.

A tornadic vortex signature, abbreviated TVS, is a Pulse-Doppler radar weather radar detected rotation algorithm that indicates the likely presence of a strong mesocyclone that is in some stage of tornadogenesis. It may give meteorologists the ability to pinpoint and track the location of tornadic rotation within a larger storm, and is one component of the National Weather Service's warning operations.

Inflow is the flow of a fluid into a large collection of that fluid. Within meteorology, inflow normally refers to the influx of warmth and moisture from air within the Earth's atmosphere into storm systems. Extratropical cyclones are fed by inflow focused along their cold front and warm fronts. Tropical cyclones require a large inflow of warmth and moisture from warm oceans in order to develop significantly, mainly within the lowest 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) of the atmosphere. Once the flow of warm and moist air is cut off from thunderstorms and their associated tornadoes, normally by the thunderstorm's own rain-cooled outflow boundary, the storms begin to dissipate. Rear inflow jets behind squall lines act to erode the broad rain shield behind the squall line, and accelerate its forward motion.

A mesovortex is a small-scale rotational feature found in a convective storm, such as a quasi-linear convective system, a supercell, or the eyewall of a tropical cyclone. Mesovortices range in diameter from tens of miles to a mile or less and can be immensely intense.

A mesohigh is a mesoscale high-pressure area that forms beneath thunderstorms. While not always the case, it is usually associated with a mesoscale convective system. In the early stages of research on the subject, the mesohigh was often referred to as a "thunderstorm high".

Project NIMROD was a meteorological field study of severe thunderstorms and their damaging winds conducted by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). It took place in the Greater Chicago area from May 15 to June 30, 1978. Data collected was from single cell thunderstorms as well as mesoscale convective systems, such as bow echoes. Using Doppler weather radars and damage clues on the ground, the team studied mesocyclones, downbursts and gust fronts. NIMROD was the first time that microbursts, very localized strong downdrafts under thunderstorms, were detected; this helped improve airport and public safety by the development of systems like the Terminal Doppler Weather Radar and the Low-level windshear alert system.

A descending reflectivity core (DRC), sometimes referred to as a blob, is a meteorological phenomenon observed in supercell thunderstorms, characterized by a localized, small-scale area of enhanced radar reflectivity that descends from the echo overhang into the lower levels of the storm. Typically found on the right rear flank of supercells, DRCs are significant for their potential role in the development or intensification of low-level rotation within these storms. The descent of DRCs has been associated with the formation and evolution of hook echoes, a key radar signature of supercells, suggesting a complex interplay between these cores and storm dynamics.