Related Research Articles

The Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, is a choral symphony, the final complete symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven, composed between 1822 and 1824. It was first performed in Vienna on 7 May 1824. The symphony is regarded by many critics and musicologists as Beethoven's greatest work and one of the supreme achievements in the history of music. One of the best-known works in common practice music, it stands as one of the most frequently performed symphonies in the world.

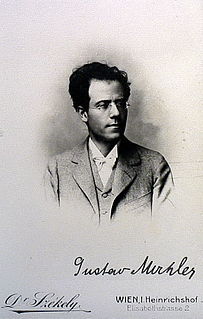

The Symphony No. 5 by Gustav Mahler was composed in 1901 and 1902, mostly during the summer months at Mahler's holiday cottage at Maiernigg. Among its most distinctive features are the trumpet solo that opens the work with a rhythmic motif similar to the opening of Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 5, the horn solos in the third movement and the frequently performed Adagietto.

The Symphony No. 1 in D major by Gustav Mahler was mainly composed between late 1887 and March 1888, though it incorporates music Mahler had composed for previous works. It was composed while Mahler was second conductor at the Leipzig Opera, Germany. Although in his letters Mahler almost always referred to the work as a symphony, the first two performances described it as a symphonic poem and as a tone poem in symphonic form respectively. The work was premièred at the Vigadó Concert Hall, Budapest, in 1889, but was not well received. Mahler made some major revisions for the second performance, given at Hamburg in October 1893; further alterations were made in the years prior to the first publication, in late 1898. Some modern performances and recordings give the work the title Titan, despite the fact that Mahler only used this label for the second and third performances, and never after the work had reached its definitive four-movement form in 1896.

The Symphony No. 8 in E-flat major by Gustav Mahler is one of the largest-scale choral works in the classical concert repertoire. As it requires huge instrumental and vocal forces it is frequently called the "Symphony of a Thousand", although the work is normally presented with far fewer than a thousand performers and the composer did not sanction that name – actually, he disapproved of it. The work was composed in a single inspired burst at his Maiernigg villa in southern Austria in the summer of 1906. The last of Mahler's works that was premiered in his lifetime, the symphony was a critical and popular success when he conducted the Munich Philharmonic in its first performance, in Munich, on 12 September 1910.

The Symphony No. 4 in G major by Gustav Mahler was composed from 1899 to 1900, though it incorporates a song originally written in 1892. That song, "Das himmlische Leben", presents a child's vision of heaven and is sung by a soprano in the symphony's Finale. Both smaller in orchestration and shorter in length than Mahler's earlier symphonies, the Fourth Symphony was initially planned to be in six movements, alternating between three instrumental and three vocal movements. The symphony's final form—begun in July 1899 at Bad Aussee and completed in August 1900 at Maiernigg—retains only one vocal movement and is in four movements: Bedächtig, nicht eilen ; In gemächlicher Bewegung, ohne Hast ; Ruhevoll,poco adagio ; and Sehr behaglich.

The Symphony No. 2 in C minor by Gustav Mahler, known as the Resurrection Symphony, was written between 1888 and 1894, and first performed in 1895. This symphony was one of Mahler's most popular and successful works during his lifetime. It was his first major work that established his lifelong view of the beauty of afterlife and resurrection. In this large work, the composer further developed the creativity of "sound of the distance" and creating a "world of its own", aspects already seen in his First Symphony. The work has a duration of 80 to 90 minutes, and is conventionally labelled as being in the key of C minor; the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians labels the work's tonality as C minor–E♭ major. It was voted the fifth-greatest symphony of all time in a survey of conductors carried out by the BBC Music Magazine.

The Symphony No. 7 by Gustav Mahler was written in 1904–05, with repeated revisions to the scoring. It is sometimes referred to by the title Song of the Night, which Mahler never knew. Although the symphony is often described as being in the key of E minor, its tonal scheme is more complicated. The symphony's first movement moves from B minor (introduction) to E minor, and the work ends with a rondo finale in C major. Thus, as Dika Newlin has pointed out, "in this symphony Mahler returns to the ideal of 'progressive tonality' which he had abandoned in the Sixth". The complexity of the work's tonal scheme was analysed in terms of "interlocking structures" by Graham George.

The Symphony No. 6 in A minor by Gustav Mahler is a symphony in four movements, composed in 1903 and 1904, with revisions from 1906. It is sometimes nicknamed the Tragic ("Tragische"), though the origin of the name is unclear.

The Symphony No. 3 in D minor by Gustav Mahler was written in 1896, or maybe only completed in that year, but composed between 1893 and 1896. It is choral, his longest piece and is the longest symphony in the standard repertoire, with a typical performance lasting around 95 to 110 minutes. It was voted one of the ten greatest symphonies of all time in a survey of conductors carried out by the BBC Music Magazine.

The Symphony No. 10 in F-sharp major by Gustav Mahler was written in the summer of 1910, and was his final composition. At the time of Mahler's death, the composition was substantially complete in the form of a continuous draft, but not fully elaborated or orchestrated, and thus not performable. Only the first movement is regarded as reasonably complete and performable as Mahler intended. Perhaps as a reflection of the inner turmoil he was undergoing at the time, the 10th Symphony is arguably his most dissonant work.

The Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Op. 93, by Dmitri Shostakovich was premiered by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky on 17 December 1953. It is not clear when it was written. According to the composer, the symphony was composed between July and October 1953, but Tatiana Nikolayeva stated that it was completed in 1951. Sketches for some of the material date from 1946.

Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 in E major, WAB 107, is one of the composer's best-known symphonies. It was written between 1881 and 1883 and was revised in 1885. It is dedicated to Ludwig II of Bavaria. The premiere, given under Arthur Nikisch and the Gewandhaus Orchestra in the opera house at Leipzig on 30 December 1884, brought Bruckner the greatest success he had known in his life. The symphony is sometimes referred to as the "Lyric", though the appellation is not the composer's own, and is seldom used.

Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 4 in E-flat major, WAB 104, is one of the composer's most popular works. It was written in 1874 and revised several times through 1888. It was dedicated to Prince Konstantin of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst. It was premiered in 1881 by Hans Richter in Vienna to great acclaim.

The E-flat clarinet is a member of the clarinet family, smaller than the more common B♭ clarinet and pitched a perfect fourth higher. It is typically considered the sopranino or piccolo member of the clarinet family and is a transposing instrument in E♭ with a sounding pitch a minor third higher than written. In Italian it is sometimes referred to as a terzino and is generally listed in B♭-based scores as terzino in Mi♭. The E-flat clarinet has a total length of about 49 cm.

The Alma Problem is an issue of concern to certain musicologists, historians and biographers who deal with the lives and works of Gustav Mahler and his wife Alma.

An organ concerto is a piece of music, an instrumental concerto for a pipe organ soloist with an orchestra. The form first evolved in the 18th century, when composers including Antonio Vivaldi, George Frideric Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach wrote organ concertos with small orchestras, and with solo parts which rarely call for the organ pedal board. During the Classical period the organ concerto became popular in many places, especially in Bavaria, Austria and Bohemia, reaching a position of being almost an integral part of the church music tradition of jubilus character. From the Romantic era fewer works are known. Finally, there are some 20th- and 21st-century examples, of which the concerto by Francis Poulenc has entered the basic repertoire, and is quite frequently played.

Anton Bruckner's String Quintet in F major, WAB 112 was composed in 1878/79 in Vienna.

Marcel Tyberg was an Austrian composer, conductor and organist. His music is late-Romantic in style.

The Concerto for Piano and Orchestra is a piano concerto by the American composer John Corigliano. The work was commissioned by the San Antonio Symphony and was first performed on April 7, 1968 by the pianist Hilde Somer and the San Antonio Symphony under the direction of Victor Alessandro. The piece is dedicated to John Atkins.

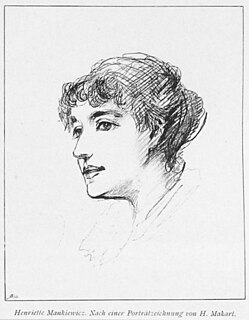

Henriette Mankiewicz was an Austrian art embroiderer.

References

- ↑ Reinhold Kubik, Margit Legler (2009). "Rhetoric, Gesture and Scenic Imagination in Bach's Music" (PDF). Understanding Bach. 4: 55–76.

- ↑ Margit Legler and Reinhold Kubik, "... in einer edeln Leibesstellung. Zur Optik der sängerischen Darbietung", in Musizierpraxis im Biedermeier: Spezifika und Kontext einer vermeintlich vertrauten Epoche (Barbara Boisits and Klaus Hubmann, editors). Hollitzer Verlag, pp. 187-204 (2004).

- ↑ Paul Banks (2021-01-07). "Symphony No. 1: the double bass solo revisited". The Music of Gustav Mahler: A Catalogue of Manuscript and Printed Sources. Retrieved 2021-05-19.

- ↑ Kenneth Woods (2011-05-26). "Mahler 1: Bass Solo means Solo Bass means One Solo Bass Playing the Bass Solo". Kenneth Woods Website. Retrieved 2021-05-19.

- ↑ Kubik, Reinhold, 'The history of the International Gustav Mahler Society in Vienna and the Complete Critical Edition', from The Cambridge Companion to Mahler (Jeremy Barham, ed.). Cambridge University Press (Cambridge, UK), ISBN 9780521832731, p. 244 (2007).

- ↑ Kubik, Reinhold (2004). "Analysis versus history: Erwin Ratz and the Sixth Symphony" (PDF). In Gilbert Kaplan (ed.). The Correct Movement Order in Mahler's Sixth Symphony. New York, New York: The Kaplan Foundation. ISBN 0-9749613-0-2.

- 1 2 3 De La Grange, Henry-Louis, Gustav Mahler, Volume 4: A New Life Cut Short, Oxford University Press (2008), pp. 1578-1587. ISBN 9780198163879.

- 1 2 3 David Hurwitz (May 2020). "Mahler: Symphony No. 6 (study score). Neue Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Reinhold Kubik, ed. C.F. Peters and Kaplan Foundation. EP 11210" (PDF). Classics Today. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ Mahlers Menschen. Freunde und Weggefährten on ZWAB

- ↑ Händels Rinaldo. Geschichte, Werk, Wirkung on WorldCat