Related Research Articles

Ānanda was the primary attendant of the Buddha and one of his ten principal disciples. Among the Buddha's many disciples, Ānanda stood out for having the best memory. Most of the texts of the early Buddhist Sutta-Piṭaka are attributed to his recollection of the Buddha's teachings during the First Buddhist Council. For that reason, he is known as the Treasurer of the Dhamma, with Dhamma referring to the Buddha's teaching. In Early Buddhist Texts, Ānanda was the first cousin of the Buddha. Although the early texts do not agree on many parts of Ānanda's early life, they do agree that Ānanda was ordained as a monk and that Puṇṇa Mantānīputta became his teacher. Twenty years in the Buddha's ministry, Ānanda became the attendant of the Buddha, when the Buddha selected him for this task. Ānanda performed his duties with great devotion and care, and acted as an intermediary between the Buddha and the laypeople, as well as the saṅgha. He accompanied the Buddha for the rest of his life, acting not only as an assistant, but also a secretary and a mouthpiece.

The Vinaya texts are texts of the Buddhist canon (Tripitaka) that also contain the rules and precepts for fully ordained monks and nuns of Buddhist Sanghas. The precepts were initially developed thirteen years after the Buddha's enlightenment. Three parallel Vinaya school traditions remain in use by modern ordained sanghas: the Theravada, Mulasarvastivada and Dharmaguptaka. In addition to these three Vinaya traditions, five other Vinaya schools of Indian Buddhism are preserved in Asian canonical manuscripts, including those of the Kāśyapīya, the Mahāsāṃghika, the Mahīśāsaka, the Sammatīya, and the Sarvāstivāda.

The early Buddhist schools are those schools into which the Buddhist monastic saṅgha split early in the history of Buddhism. The divisions were originally due to differences in Vinaya and later also due to doctrinal differences and geographical separation of groups of monks. The original saṅgha split into the first early schools during or after the reign of Aśoka. Later, these first early schools were further divided into schools such as the Sarvāstivādins, the Dharmaguptakas, and the Vibhajyavāda, and ended up numbering 18 or 20 schools according to traditional accounts.

The Council of Jerusalem or Apostolic Council is a council described in chapter 15 of the Acts of the Apostles, held in Jerusalem around c. 48–50 AD.

Buddhist eschatology, like many facets of modern Buddhist practice and belief, came into existence during its development in China, and, through the blending of Buddhist cosmological understanding and Daoist eschatological views, created a complex canon of apocalyptic beliefs. These beliefs, although not entirely part of orthodox Buddhism, form an important collection of Chinese Buddhist traditions which bridge the gap between the monastic order and local beliefs of Imperial China.

Since the death of the historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, Buddhist monastic communities ("sangha") have periodically convened to settle doctrinal and disciplinary disputes and to revise and correct the contents of the Buddhist canons. These gatherings are often termed Buddhist "councils". Accounts of these councils are recorded in Buddhist texts as having begun immediately following the death of the Buddha and have continued into the modern era. The earliest councils are regarded as real events by every Buddhist tradition. However, the historicity and details of these councils remains a matter of dispute in modern Buddhist studies. This is because various sources belonging to different Buddhist schools contain conflicting accounts of these events and the narratives often serve to bolster the authority and prestige of specific schools.

Mahākāśyapa was one of the principal disciples of Gautama Buddha. He is regarded in Buddhism as an enlightened disciple, being foremost in ascetic practice. Mahākāśyapa assumed leadership of the monastic community following the parinirvāṇa (death) of the Buddha, presiding over the First Buddhist Council. He was considered to be the first patriarch in a number of Early Buddhist schools and continued to have an important role as patriarch in the Chan/Zen tradition. In Buddhist texts, he assumed many identities, that of a renunciant saint, a lawgiver, an anti-establishment figure, but also a "guarantor of future justice" in the time of Maitreya, the future Buddha—he has been described as "both the anchorite and the friend of mankind, even of the outcast".

Kriyananda was an American Hindu religious leader, yoga guru, meditation teacher, musician, and author. He was a direct disciple of Paramahansa Yogananda and founder of the spiritual movement named "Ananda". He wrote numerous songs and dozens of books. According to the LA Times, the main themes of his work were compassion and humility, but he was a controversial figure. Kriyananda and Ananda were sued for copyright issues, sexual harassment, and later, for alleged fraud and labor-law violations.

"Mirror Image" is a science fiction short story by American writer Isaac Asimov, originally published in the May 1972 issue Analog Science Fiction and Fact, and collected in The Best of Isaac Asimov (1973), The Complete Robot (1982), Robot Visions (1990), and The Complete Stories, Volume 2 (1992).

Upāli was a monk, one of the ten chief disciples of the Buddha and, according to early Buddhist texts, the person in charge of the reciting and reviewing of monastic discipline on the First Buddhist Council. Upāli belongs to the barber community. He met the Buddha when still a child, and later, when the Sakya princes received ordination, he did so as well. He was ordained before the princes, putting humility before caste. Having been ordained, Upāli learnt both Buddhist doctrine and vinaya. His preceptor was Kappitaka. Upāli became known for his mastery and strictness of vinaya and was consulted often about vinaya matters. A notable case he decided was that of the monk Ajjuka, who was accused of partisanship in a conflict about real estate. During the First Council, Upāli received the important role of reciting the vinaya, for which he is mostly known.

Kātyāyana or Mahākātyāyana was a disciple of Gautama Buddha. He is listed as one of the ten principal disciples and was foremost in expanding on and explaining brief statements of the Buddha.

A sāmaṇera (Pali), Sanskrit: श्रामणेर, is a novice male monk in a Buddhist context. A female novice nun is a sāmaṇerī (Pali), and a śrāmaṇerī or śrāmaṇerikā (Sanskrit). In Tibetan and in Tibetan Buddhism, a female novice nun is a getsulma, and a male novice monk is a getsul.

Moggaliputtatissa, was a Buddhist monk and scholar who was born in Pataliputra, Magadha and lived in the 3rd century BCE. He is associated with the Third Buddhist council, the Mauryan emperor Ashoka and the Buddhist missionary activities which took place during his reign.

Kosambi (Pali) or Kaushambi (Sanskrit) was an ancient city in India, characterized by its importance as a trading center along the Ganges Plain and its status as the capital of the Vatsa Kingdom, one of the sixteen mahajanapadas. It was located on the Yamuna River about 56 kilometres (35 mi) southwest of its confluence with the Ganges at Prayaga, which made it a powerful center for trade and beneficial for the Vatsa Kingdom.

Anuruddha was one of the ten principal disciples and a cousin of Gautama Buddha.

Khandhaka is the second book of the Theravadin Vinaya Pitaka and includes the following two volumes:

The Buddha was born into a noble family in Lumbini in 563 BCE as per historical events and 624 BCE according to Buddhist tradition. He was called Siddhartha Gautama in his childhood. His father was king Śuddhodana, leader of the Shakya clan in what was the growing state of Kosala, and his mother was queen Maya. According to Buddhist legends, the baby exhibited the marks of a great man. A prophecy indicated that, if the child stayed at home, he was destined to become a world ruler. If the child left home, however, he would become a universal spiritual leader. To make sure the boy would be a great king and world ruler, his father isolated him in his palace and he was raised by his mother's younger sister, Mahapajapati Gotami, after his mother died just seven days after childbirth.

The ten principal disciples were the main disciples of Gautama Buddha. Depending on the scripture, the disciples included in this group vary. In many Mahāyāna discourses, these ten disciples are mentioned, but in differing order. The ten disciples can be found as an iconographic group in notable places in the Mogao Caves. They are mentioned in Chinese texts from the fourth century BCE until the twelfth century CE, and are the most honored of the groups of disciples, especially so in China and Central Asia. The ten disciples are mentioned in the Mahāyāna text Vimalakīrti-nideśa, among others. In this text, they are called the "Ten Wise Ones", a term which is normally used for the disciples of Confucius.

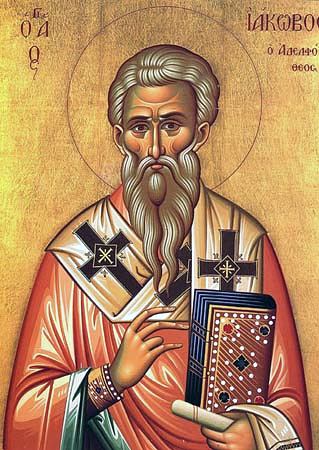

Ignatius IV (Youssef) Sarrouf was Patriarch of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church in 1812. He is remembered for both his patriarchate, and for having been, as metropolitan of Beirut, a leading figure in the early history of the Melkite Church.

Bhāṇaka were Buddhist monks who specialized in the memorization and recitation of a specific collection of texts within the Buddhist canon. Lineages of bhāṇakas were responsible for preserving and transmitting the teachings of the Buddha until the canon was committed to writing in the 1st century BC, and declined as the oral transmission of early Buddhism was replaced by writing.

References

- Tr. Horner, IB.The Book of the Discipline vol-v (Culavagga)London:Luzac& Company Ltd,1952.