Related Research Articles

Fascism is a form of far-right, authoritarian ultranationalism characterized by dictatorial power, forcible suppression of opposition, as well as strong regimentation of society and of the economy which came to prominence in early 20th-century Europe. The first fascist movements emerged in Italy during World War I, before spreading to other European countries. Opposed to liberalism, Marxism, and anarchism, fascism is placed on the far right within the traditional left–right spectrum.

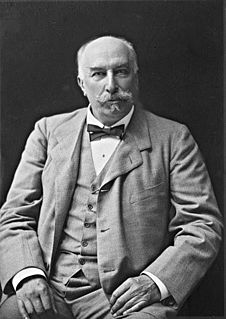

Giovanni Giolitti was an Italian statesman. He was the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history, after Benito Mussolini. He was a prominent leader of the Historical Left and the Liberal Union. Giolitti is widely considered one of the most powerful and important politicians in Italian history and, due to his dominant position in Italian politics, he was accused by critics of being a parliamentary dictator.

The March on Rome was an organized mass demonstration in October 1922, which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, Fascist Party leaders planned an insurrection, to take place on 28 October. When fascist troops entered Rome, Prime Minister Luigi Facta wished to declare a state of siege, but this was overruled by King Victor Emmanuel III. On the following day, 29 October 1922, the King appointed Mussolini as Prime Minister, thereby transferring political power to the fascists without armed conflict.

Michele Bianchi was an Italian revolutionary syndicalist leader who took a position in the Unione Italiana del Lavoro (UIL) He was among the founding members of the Fascist movement. He was widely seen as the dominant leader of the leftist, syndicalist wing of the National Fascist Party. He took an active role in the "interventionist left" where he "espoused an alliance between nationalism and syndicalism." He was one of the most influential politicians of the regime before his succumbing to tuberculosis in 1930. He was also one of the grand architects behind the "Great List" which secured the parliamentary majority in favor of the fascists.

Alceste De Ambris, was an Italian syndicalist, the brother of politician Amilcare De Ambris. De Ambris had a major part to play in the agrarian strike actions of 1908.

Fascio is an Italian word literally meaning "a bundle" or "a sheaf", and figuratively "league", and which was used in the late 19th century to refer to political groups of many different orientations. A number of nationalist fasci later evolved into the 20th century Fasci movement, which became known as fascism.

Red Week was the name given to a week of unrest which occurred from 7 to 14 June 1914. Over these seven days, Italy saw widespread rioting and large-scale strikes throughout the Italian provinces of Romagna and the Marche.

The history of fascist ideology is long and draws on many sources. Fascists took inspiration from sources as ancient as the Spartans for their focus on racial purity and their emphasis on rule by an elite minority. Fascism has also been connected to the ideals of Plato, though there are key differences between the two. Fascism styled itself as the ideological successor to Rome, particularly the Roman Empire. The concept of a "high and noble" Aryan culture as opposed to a "parasitic" Semitic culture was core to Nazi racial views. From the same era, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's view on the absolute authority of the state also strongly influenced Fascist thinking. The French Revolution was a major influence insofar as the Nazis saw themselves as fighting back against many of the ideas which it brought to prominence, especially liberalism, liberal democracy and racial equality, whereas on the other hand Fascism drew heavily on the revolutionary ideal of nationalism. Common themes among fascist movements include; nationalism, hierarchy and elitism, militarism, quasi-religion, masculinity and philosophy. Other aspects of fascism such as its "myth of decadence", anti‐egalitarianism and totalitarianism can be seen to originate from these ideas. These fundamental aspects however, can be attributed to a concept known as "Palingenetic ultranationalism", a theory proposed by Roger Griffin, that fascism is a synthesis of totalitarianism and ultranationalism sacralized through myth of national rebirth and regeneration.

Filippo Turati was an Italian sociologist, criminologist, poet and socialist politician.

Italian Fascism, also known as Classical Fascism or simply Fascism, is the original fascist ideology as developed in Italy by Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini. The ideology is associated with a series of three political parties led by Benito Mussolini; the National Fascist Party (PNF), which ruled the Kingdom of Italy from 1922 until 1943, and the Republican Fascist Party that ruled the Italian Social Republic from 1943 to 1945. Italian Fascism is also associated with the post-war Italian Social Movement and subsequent Italian neo-fascist movements.

The Italian Fasces of Combat, initially known as Fasces of Revolutionary Action, was an Italian fascio organization, created by Benito Mussolini in 1919.

Squadrismo is the movement of squadre d’azione, which was a non-state organised fascist militia, led by local leaders called ‘Ras’. The militia originally consisted of farmers and the middle-class creating their own defense against revolutionary socialists. Squadrismo became an important asset for the rise of the fascist party led by Mussolini, by using violence to systematically eliminate any political parties which were opposed to Fascism. This violence was not solely an instrument in politics, but was also a vital component of squadrismo identity, which made it difficult for the movement to be tamed. This was shown in the various attempts by Mussolini to control squadrismo violence, with the Pact of Pacification, and finally with the Consolidated Public Safety Act. Squadrismo, which ultimately became the Blackshirts, served as a source of inspiration for Adolf Hitler’s S.A.

The National Fascist Party was an Italian political party, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian Fascism. The party ruled the Kingdom of Italy from 1922 when Fascists took power with the March on Rome until the fall of the Fascist regime in 1943, when Mussolini was deposed by the Grand Council of Fascism.

The Arditi del Popolo was an Italian militant anti-fascist group founded at the end of June 1921 to resist the rise of Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party and the violence of the Blackshirts (squadristi) paramilitaries. It grouped revolutionary trade-unionists, socialists, communists, anarchists, republicans, as well as some former military officers, and was co-founded by Mingrino, Argo Secondari, Gino Lucetti – who tried to assassinate Mussolini on 11 September 1926 – the deputy Guido Picelli and others. The Arditi del Popolo were an offshoot of the Arditi elite troops, who had previously occupied Fiume in 1919 behind the poet Gabriele d'Annunzio, who proclaimed the Italian Regency of Carnaro. Those who split to form the Arditi del Popolo were close to the anarchist Argo Secondari and were supported by Mario Carli. The formazioni di difesa proletaria later merged with them. The Arditi gathered approximately 20,000 members in summer 1921.

Fascism in Europe was the set of various fascist ideologies practiced by governments and political organizations in Europe during the 20th century. Fascism was born in Italy following World War I, and other fascist movements, influenced by Italian Fascism, subsequently emerged across Europe. Among the political doctrines identified as ideological origins of fascism in Europe are the combining of a traditional national unity and revolutionary anti-democratic rhetoric espoused by integral nationalist Charles Maurras and revolutionary syndicalist Georges Sorel in France.

Nicola Bombacci, born at Civitella di Romagna, was an Italian Marxist revolutionary, prominent during the first half of the 20th century. He began in the Italian Socialist Party as an opponent of the reformist wing and became a founding member of the Communist Party of Italy in 1921, sitting on the fifteen-man Central Committee. During the latter part of his life, particularly during the Second World War, Bombacci allied with Benito Mussolini and the Italian Social Republic against the Allied invasion of Italy. He met his death after being shot by communist partisans and his cadaver was subsequently strung up in Piazzale Loreto.

Cesare Rossi was an Italian fascist leader who later became estranged from the regime.

The Pact of Pacification or Pacification Pact was a peace agreement officially signed by Mussolini and other leaders of the Fasci with the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) and the General Confederation of Labor (CGL) in Rome on August 2 or 3, 1921. The Pact called for “immediate action to put an end to the threats, assaults, reprisals, acts of vengeance, and personal violence of any description,” by either side for the “mutual respect” of “all economic organizations.” The Italian Futurists, Syndicalists and others favored Mussolini’s peace pact as an attempt at “reconciliation with the Socialists.” Others saw it as a means to form a “grand coalition of new mass parties” to “overthrow the liberal systems,” via parliament or civil society.

Events from the year 1921 in Italy.

Fascist syndicalism was a trade syndicate movement that rose out of the pre-World War II provenance of the revolutionary syndicalism movement led mostly by Edmondo Rossoni, Sergio Panunzio, A. O. Olivetti, Michele Bianchi, Alceste De Ambris, Paolo Orano, Massimo Rocca, and Guido Pighetti, under the influence of Georges Sorel, who was considered the “‘metaphysician’ of syndicalism.” The Fascist Syndicalists differed from other forms of fascism in that they generally favored class struggle, worker-controlled factories and hostility to industrialists, which lead historians to portray them as “leftist fascist idealists” who “differed radically from right fascists.” Generally considered one of the more radical Fascist syndicalists in Italy, Rossoni was the “leading exponent of fascist syndicalism.”, and sought to infuse nationalism with “class struggle.”

References

- ↑ Benito Mussolini (2006), My Autobiography with The Political and Social Doctrine of Fascism, Mineloa: NY: Dover Publication Inc., p. 227. Benito Mussolini, "The Political and Social Doctrine of Fascism," Jane Soames, trans., Leonard and Virginia Woolf (Hogarth Press), London W.C., 1933, p. 7 Note that some historians refer to this political party as "The Revolutionary Fascist Party"

- ↑ Charles F. Delzell, edit., Mediterranean Fascism 1919-1945, New York, NY, Walker and Company, 1971, p. 96

- ↑ Denis Mack Smith, Mussolini, New York, NY, Vintage Books, 1983, p. 38

- ↑ Denis Mack Smith, Modern Italy: A Political History, University of Michigan Press, 1979, pp. 284, 297

- ↑ Denis Mack Smith, Mussolini, New York, NY, Vintage Books, 1983, p. 38

- ↑ Martin Clark, Mussolini (Profiles in Power), Routledge, 2014, p. 44

- ↑ Thomas Streissguth, Lora Friedenthal, Isolationism (Key Concepts in American History), New York, NY, Chelsea House Publishers, 2010, p. 57

- ↑ John Foot, Modern Italy, New York, NY, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, p. 233

- ↑ Ernst Nolte, The Three Faces of Fascism: Action Française, Italian Fascism, National Socialism, Henry Holt & Company, Inc.; first edition, 1966, p. 154

- ↑ Ernst Nolte, The Three Faces of Fascism: Action Française, Italian Fascism, National Socialism, Henry Holt & Company, Inc.; first edition, 1966, p. 203

- ↑ Ernst Nolte, The Three Faces of Fascism: Action Française, Italian Fascism, National Socialism, Henry Holt & Company, Inc.; first edition, 1966, p. 206, Opera Omnia di Benito Mussolini, XVII, 21, p. 66

- ↑ Richard Pipes, Russia Under The Bolshevik Regime, New York: NY, Vintage Books, 1995, p. 253

- ↑ Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism, 1914-1945, University of Wisconsin Press, 1995, p. 99

- ↑ Charles F. Delzell, edit., Mediterranean Fascism 1919-1945, New York, NY, Walker and Company, 1971, p. 26

- ↑ Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism, 1914-1945, University of Wisconsin Press, 1995, p. 100

- ↑ Charles F. Delzell, edit., Mediterranean Fascism 1919-1945, New York, NY, Walker and Company, 1971, p. 26

- ↑ Joel Krieger, ed., The Oxford Companion to Comparative Politics, Oxford University Press, 2012, p. 120