Limestone is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of CaCO3. Limestone forms when these minerals precipitate out of water containing dissolved calcium. This can take place through both biological and nonbiological processes, though biological processes, such as the accumulation of corals and shells in the sea, have likely been more important for the last 540 million years. Limestone often contains fossils which provide scientists with information on ancient environments and on the evolution of life.

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support the life of plants and soil organisms. Some scientific definitions distinguish dirt from soil by restricting the former term specifically to displaced soil.

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles to settle in place. The particles that form a sedimentary rock are called sediment, and may be composed of geological detritus (minerals) or biological detritus. The geological detritus originated from weathering and erosion of existing rocks, or from the solidification of molten lava blobs erupted by volcanoes. The geological detritus is transported to the place of deposition by water, wind, ice or mass movement, which are called agents of denudation. Biological detritus was formed by bodies and parts of dead aquatic organisms, as well as their fecal mass, suspended in water and slowly piling up on the floor of water bodies. Sedimentation may also occur as dissolved minerals precipitate from water solution.

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk is common throughout Western Europe, where deposits underlie parts of France, and steep cliffs are often seen where they meet the sea in places such as the Dover cliffs on the Kent coast of the English Channel.

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals through contact with water, atmospheric gases, sunlight, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs in situ, and so is distinct from erosion, which involves the transport of rocks and minerals by agents such as water, ice, snow, wind, waves and gravity.

Soil formation, also known as pedogenesis, is the process of soil genesis as regulated by the effects of place, environment, and history. Biogeochemical processes act to both create and destroy order (anisotropy) within soils. These alterations lead to the development of layers, termed soil horizons, distinguished by differences in color, structure, texture, and chemistry. These features occur in patterns of soil type distribution, forming in response to differences in soil forming factors.

A concretion is a hard, compact mass formed by the precipitation of mineral cement within the spaces between particles, and is found in sedimentary rock or soil. Concretions are often ovoid or spherical in shape, although irregular shapes also occur. The word 'concretion' is derived from the Latin concretio "(act of) compacting, condensing, congealing, uniting", itself from con meaning 'together' and crescere meaning "to grow". Concretions form within layers of sedimentary strata that have already been deposited. They usually form early in the burial history of the sediment, before the rest of the sediment is hardened into rock. This concretionary cement often makes the concretion harder and more resistant to weathering than the host stratum.

Dolomite (also known as dolomite rock, dolostone or dolomitic rock) is a sedimentary carbonate rock that contains a high percentage of the mineral dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2. It occurs widely, often in association with limestone and evaporites, though it is less abundant than limestone and rare in Cenozoic rock beds (beds less than about 66 million years in age). The first geologist to distinguish dolomite from limestone was Déodat Gratet de Dolomieu; a French mineralogist and geologist whom it is named after. He recognized and described the distinct characteristics of dolomite in the late 18th century, differentiating it from limestone.

The pedosphere is the outermost layer of the Earth that is composed of soil and subject to soil formation processes. It exists at the interface of the lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere and biosphere. The pedosphere is the skin of the Earth and only develops when there is a dynamic interaction between the atmosphere, biosphere, lithosphere and the hydrosphere. The pedosphere is the foundation of terrestrial life on Earth.

A ganister is hard, fine-grained quartzose sandstone, or orthoquartzite, used in the manufacture of silica brick typically used to line furnaces. Ganisters are cemented with secondary silica and typically have a characteristic splintery fracture.

Bioturbation is defined as the reworking of soils and sediments by animals or plants. It includes burrowing, ingestion, and defecation of sediment grains. Bioturbating activities have a profound effect on the environment and are thought to be a primary driver of biodiversity. The formal study of bioturbation began in the 1800s by Charles Darwin experimenting in his garden. The disruption of aquatic sediments and terrestrial soils through bioturbating activities provides significant ecosystem services. These include the alteration of nutrients in aquatic sediment and overlying water, shelter to other species in the form of burrows in terrestrial and water ecosystems, and soil production on land.

In the geosciences, paleosol is an ancient soil that formed in the past. The precise definition of the term in geology and paleontology is slightly different from its use in soil science.

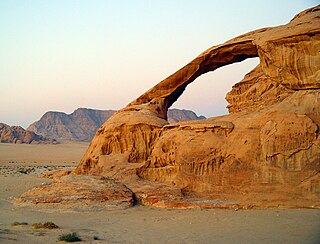

Caliche is a sedimentary rock, a hardened natural cement of calcium carbonate that binds other materials—such as gravel, sand, clay, and silt. It occurs worldwide, in aridisol and mollisol soil orders—generally in arid or semiarid regions, including in central and western Australia, in the Kalahari Desert, in the High Plains of the western United States, in the Sonoran Desert, Chihuahuan Desert and Mojave Desert of North America, and in eastern Saudi Arabia at Al-Hasa. Caliche is also known as calcrete or kankar. It belongs to the duricrusts. The term caliche is borrowed from Spanish and is originally from the Latin word calx, meaning lime.

Carbonate rocks are a class of sedimentary rocks composed primarily of carbonate minerals. The two major types are limestone, which is composed of calcite or aragonite (different crystal forms of CaCO3), and dolomite rock (also known as dolostone), which is composed of mineral dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2). They are usually classified based on texture and grain size. Importantly, carbonate rocks can exist as metamorphic and igneous rocks, too. When recrystallized carbonate rocks are metamorphosed, marble is created. Rare igneous carbonate rocks even exist as intrusive carbonatites and, even rarer, there exists volcanic carbonate lava.

Paleopedology is the discipline that studies soils of past geological eras, from quite recent (Quaternary) to the earliest periods of the Earth's history. Paleopedology can be seen either as a branch of soil science (pedology) or of paleontology, since the methods it uses are in many ways a well-defined combination of the two disciplines.

Calcareous is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

The phosphorus cycle is the biogeochemical cycle that describes the movement of phosphorus through the lithosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere. Unlike many other biogeochemical cycles, the atmosphere does not play a significant role in the movement of phosphorus, because phosphorus and phosphorus-based compounds are usually solids at the typical ranges of temperature and pressure found on Earth. The production of phosphine gas occurs in only specialized, local conditions. Therefore, the phosphorus cycle should be viewed from whole Earth system and then specifically focused on the cycle in terrestrial and aquatic systems.

Shallow water marine environment refers to the area between the shore and deeper water, such as a reef wall or a shelf break. This environment is characterized by oceanic, geological and biological conditions, as described below. The water in this environment is shallow and clear, allowing the formation of different sedimentary structures, carbonate rocks, coral reefs, and allowing certain organisms to survive and become fossils.

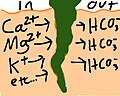

The calcium cycle is a transfer of calcium between dissolved and solid phases. There is a continuous supply of calcium ions into waterways from rocks, organisms, and soils. Calcium ions are consumed and removed from aqueous environments as they react to form insoluble structures such as calcium carbonate and calcium silicate, which can deposit to form sediments or the exoskeletons of organisms. Calcium ions can also be utilized biologically, as calcium is essential to biological functions such as the production of bones and teeth or cellular function. The calcium cycle is a common thread between terrestrial, marine, geological, and biological processes. Calcium moves through these different media as it cycles throughout the Earth. The marine calcium cycle is affected by changing atmospheric carbon dioxide due to ocean acidification.