Saint Helena is a British possession in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island 1,950 kilometres west of the coast of south-western Africa, and 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi) east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constituent parts of the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha.

Saint Helena has a known history of over 500 years since its recorded discovery by the Portuguese in 1502. Claiming to be Britain's second oldest colony, after Bermuda, this is one of the most remote settlements in the world and was for several centuries of vital strategic importance to ships sailing to Europe from Asia and South Africa. Since the early 19th century, the British occasionally used the island as a place of exile, most notably for Napoleon Bonaparte, Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo and over 5,000 Boer prisoners.

Gaspard, Baron Gourgaud, also known simply as Gaspard Gourgaud, was a French soldier, prominent in the Napoleonic wars.

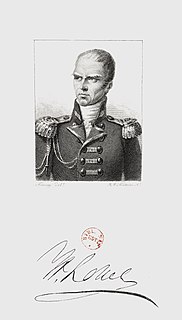

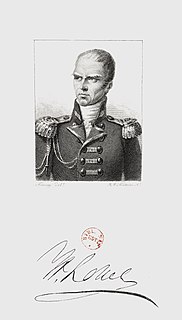

Sir Hudson Lowe was an Anglo-Irish soldier and colonial administrator who is best known for his time as Governor of St Helena, where he was the "gaoler" of the Emperor Napoléon.

Jamestown is the capital city of the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, located on the island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is also the historic main settlement of the island and is on its north-western coast. Before the development of the port at Rupert's Bay, it was the island's only port and the centre of the island's road and communications network. It was founded when colonists from the English East India Company settled on the island in 1659 and was briefly occupied by the Dutch East India Company in 1673 before being recaptured. Many of the buildings built by the East India Company in the 18th century survive and give the town its distinctive Georgian flavour.

Longwood is a settlement and a district of the British island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean.

Longwood House is a mansion in St. Helena and the final residence of Napoleon Bonaparte, the former Emperor of the French, during his exile on the island of Saint Helena, from 10 December 1815 until his death on 5 May 1821.

James Roche Verling was a British Army surgeon who became personal surgeon to Napoleon Bonaparte on St Helena.

Briars is the name of the small pavilion in which Napoleon Bonaparte stayed for the first few weeks of his exile on Saint Helena in late 1815 before being moved to Longwood House.

The Diocese of Saint Helena is an Anglican diocese within the Anglican Church of Southern Africa. It covers the islands of Saint Helena and Ascension in the Atlantic Ocean and was created in 1859. St Paul's Cathedral is on Saint Helena.

During the time of Napoleon Bonaparte, it was customary to cast a death mask of a great leader who had recently died. A mixture of wax or plaster was carefully placed over Napoleon's face and removed after the form had hardened. From this impression, subsequent copies were cast. Much mystery and controversy surrounds the origins and whereabouts of the most original cast moulds. There are only four genuine bronze death masks known to exist.

Alarm Forest is the newest of the eight districts of the island of Saint Helena, part of the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is located southeast of Jamestown, in the interior of the island, and is the only district to lack a coastline.

Vice-Admiral Robert Plampin was a British Royal Navy officer during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, serving in the American Revolutionary War, the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars, but best known for his time as commander of the British colony of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic during the period when former Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte was imprisoned there. Born into a Navy family, Plampin went to sea at age 13 and fought throughout the American Revolutionary War, based principally in the Caribbean Sea. During the French Revolutionary Wars, Plampin served in a number of ships with mixed success, once being involved in a shipwreck and twice serving ashore during sieges. After the Peace of Amiens, Plampin took command of the ship of the line HMS Powerful and operated successfully in the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean. In 1816, following the defeat and capture of the French Emperor, Plampin was placed in command of the squadron at the Cape of Good Hope, which also had responsibility for Saint Helena, which Plampin regularly visited and had numerous conversations with Napoleon.

Saint Matthew is a church on the island of Saint Helena and is part of the Diocese of St Helena. It is situated in Hutt's Gate in the Longwood district. The church opened in 1862. It is designated as a Grade II listed building.

Lucia Elizabeth Balcombe Abell was a friend of Napoleon I during his exile at Saint Helena. She was also an author and a landowner in New South Wales, Australia.

François Carlo Antommarchi was Napoleon's physician from 1818 to his death in 1821.

The French domains of Saint Helena is an estate of 14 ha, in three separate parts, on the island of Saint Helena within the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha.

Michel Dancoisne-Martineau is the director of the French domains of Saint Helena. Since October 1990, he has been Honorary French Consul on the island.

War. The Exile and the Rock Limpet is an oil painting of 1842 by the English Romantic painter J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851). Intended to be a companion piece to Turner's Peace – Burial at Sea, War is a painting that depicts a moment from Napoleon Bonaparte's exile at Saint Helena. In December 1815, the former Emperor was taken by the British government to the Longwood House, despite its state of disrepair, to live in captivity; during his final years of isolation, Napoleon had fallen into despair. Turner's decision to pair the painting with Peace was heavily criticized when it was first exhibited but it is also seen as predecessor to his more famous piece Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway (1844).

The Valley of the Tomb is the site of Napoleon's tomb, on the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena in the south Atlantic Ocean, where he was buried following his death in exile on 5 May 1821. The valley had been called the Sane Valley, but Napoleon had taken walks there and referred to it as the Valley of the Geraniums.