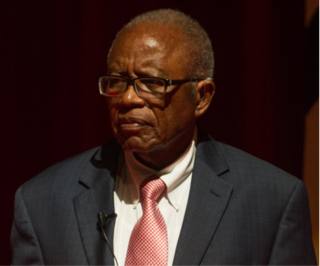

Richard Henry Harris, Jr. (August 22, 1918 - July 24, 1976) was a prominent civil rights leader and pharmacist. A personal friend, neighbor and collaborator of Dr Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery, Alabama, Harris was instrumental in three of the most seminal protests of the U.S. civil rights movement: the Freedom Riders, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Selma to Montgomery marches. Harris's home, best known as the famed “Richard Harris House”, was Montgomery, Alabama’s central command center and safe haven for beaten and bloodied Freedom Riders as they traveled to Jackson, Mississippi amidst physically violent racial rioters, National Guard protection, and Alabama segregationist authorities’ call for martial law. [1] [2]

In 2018, the World Monuments Fund (WMF) listed Harris’ home on its World Monuments Watch list of 20 threatened cultural sites not only for the potential risk to its physical structure, but the potential risk to its historical significance and backstory. [3] [4]

A former U.S. Army Air Force Captain, Harris was one of the U.S. military's first African American combat fighter pilots, serving with the prodigious 332nd Fighter Group's 99th Fighter Squadron, best known as the Tuskegee Airmen, "Red Tails," or “Schwartze Vogelmenschen” ("Black Birdmen") among enemy German pilots. [5]

Harris was born on August 22, 1918, in Montgomery, Alabama. He was the son of Richard Henry Harris, Sr. (1888 - February 1, 1944) and Evelyn “Everlena” Cook Jones (1884 - 1974). [6] [7] In 1907, Harris Sr founded and operated Dean Drug Store, Montgomery, Alabama's oldest African American drug store. [8] The store was located at 147 Monroe Street in Montgomery's historically African American business district. When Harris Sr. died in 1944, his wife Evelyn assumed ownership. The store was listed to the National Register of Historic Places before the city demolished it in the 1980s. [9]

Harris was also the maternal grandson of John W. Jones (Alabama politician), an Alabama state senator during Reconstruction. [10]

Harris attended Alabama State College laboratory school for primary and secondary school. The Harris Family later moved to Tuskegee, Alabama where they lived with the Foster Family, the maternal grandparents of famed musical performer and songwriter Lionel Richie. [11]

Harris attended the now -defunct Tuskegee Military Academy for Boys, graduating on May 23, 1935. In 1937, Harris graduated from Williston Academy for boys (now the Williston Northampton School in East Hampton, Massachusetts, a college preparatory school. [12]

In late 1937, Harris enrolled at the prestigious Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, graduating with a bachelor's degree in mathematics in 1941. [13] Though he relocated to Chicago, Illinois to attend graduate school, Harris plans changed after the U.S. selective service drafted him to the US military. [14]

During his US military training at the Walterboro Air Field in Walterboro, South Carolina, Harris met Vera McGill, a Charleston, South Carolina native. On September 5, 1945, the couple married at Godman Field in Louisville, Kentucky. They had four children: Adrian Harris, Valda Harris, Richard Harris III, and John Harris. [15]

In 1942, the U.S. Army Air Corps admitted Harris to its aviation cadet program in Tuskegee, Alabama. On June 30, 1943, Harris graduated as a member of the Single Engine Section Cadet Class SE-43-F, receiving his wings and commission as a 2nd Lieutenant. [16] The US Army Air Corps assigned Harris to the 332nd Fighter Group’s 99th Fighter Squadron. [17] [18]

In 1946, the US Army Air Corps discharged Harris with the rank of captain. [19] [20]

After leaving the US military in 1946, Harris returned to Montgomery, Alabama, working at his mother’s Dean Drug Store located at 147 Monroe Street, under the tutelage of pharmacist Russell Smith. [21] In May 1953, Harris graduated with a pharmacy degree from the Xavier University of Louisiana School of Pharmacy in New Orleans, Louisiana. After returning to Montgomery, Harris became Dean Drug Store’s owner and operator. [22]

A personal friend, neighbor and collaborator of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Harris was instrumental in three of the most seminal protests of the U.S. civil rights movement: the Freedom Riders, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Selma to Montgomery marches. At age 26, Harris helped Dr. King organize Montgomery protests, leading the charge in communication and transportation. [23] [24] Wearing a phone headset at his pharmacy, Harris simultaneously dispatched vehicles while filling prescriptions for his customers. He also lent out his Dean Drug Store as a secure meeting space for civil rights meetings. [25]

Harris’s historic Centennial Hill neighborhood home, best known as the “Richard Harris House”, was Montgomery, Alabama’s central command center for thirty-three beaten and bloodied Freedom Riders protesters from Nashville, Tennessee making their way to Jackson, Mississippi between May 20 and May 24, 1961 to protest segregation in interstate transportation. [26] [27] White racist rioters attacked the Freedom Riders as they arrived at the Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station, beating them with baseball bats and iron pipes. [28] [29] [30] The National Guard brought the wounded Freedom Riders to Harris’ home where Harris fed them and provided them with medicines.

Civil rights leaders Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy, James Farmer, John Lewis, and Diane Nash met at Harris’ home to develop strategy to buffer and support the Freedom Riders’ protests. [31]

Harris also collaborated with Dr. King followed famed civil rights activist Rosa Parks’s 1955 arrest for refusing to switch seats on a segregated local transit bus, prompting the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Harris used his pharmacy’s parking lot as a routing center for African American citizens requiring transportation to their jobs in lieu of riding the public buses. [32] [33]

In March 1965, Harris worked with local African American physicians at St. Jude’s Hospital to treat African American protesters beaten up by law enforcement at the Selma to Montgomery marches for voting rights. [34]

The Tuskegee Airmen was a group of primarily African American military pilots and airmen who fought in World War II. They formed the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group (Medium) of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF). The name also applies to the navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, instructors, crew chiefs, nurses, cooks, and other support personnel. The Tuskegee airmen received praise for their excellent combat record earned while protecting American bombers from enemy fighters. The group was awarded three Distinguished Unit Citations.

Tuskegee is a city in Macon County, Alabama, United States. General Thomas Simpson Woodward, a Creek War veteran under Andrew Jackson, laid out the city and founded it in 1833. It became the county seat in the same year and it was incorporated in 1843. It is the most populous city in Macon County. At the 2020 census the population was 9,395, down from 9,865 in 2010 and 11,846 in 2000.

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. The marches were organized by nonviolent activists to demonstrate the desire of African-American citizens to exercise their constitutional right to vote, in defiance of segregationist repression; they were part of a broader voting rights movement underway in Selma and throughout the American South. By highlighting racial injustice, they contributed to passage that year of the Voting Rights Act, a landmark federal achievement of the civil rights movement.

Amelia Isadora Platts Boynton Robinson was an American activist who was a leader of the American Civil Rights Movement in Selma, Alabama, and a key figure in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches.

Diane Judith Nash is an American civil rights activist, and a leader and strategist of the student wing of the Civil Rights Movement.

Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, at Moton Field in Tuskegee, Alabama, commemorates the contributions of African-American airmen in World War II. Moton Field was the site of primary flight training for the pioneering pilots known as the Tuskegee Airmen, and is now operated by the National Park Service to interpret their history and achievements. It was constructed in 1941 as a new training base. The field was named after former Tuskegee Institute principal Robert Russa Moton, who died the previous year.

Fred David Gray is an American civil rights attorney, preacher, activist, and state legislator from Alabama. He handled many prominent civil rights cases, such as Browder v. Gayle, and was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives in 1970, along with Thomas Reed, both from Tuskegee. They were the first black state legislators in Alabama in the 20th century. He served as the president of the National Bar Association in 1985, and in 2001 was elected as the first African-American President of the Alabama State Bar.

Evelyn Gibson Lowery was an American civil rights activist and leader.

Lee Andrew Archer, Jr. was an American fighter Ace in the 332nd Fighter Group, commonly known as the Tuskegee Airmen, during World War II. He was one of the first African American military aviators in the United States Army Air Corps, the United States Army Air Forces and later the United States Air Force, eventually earning the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Bernard LafayetteJr. is an American civil rights activist and organizer, who was a leader in the Civil Rights Movement. He played a leading role in early organizing of the Selma Voting Rights Movement; was a member of the Nashville Student Movement; and worked closely throughout the 1960s movements with groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the American Friends Service Committee.

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. The Southern states had ignored the rulings and the federal government did nothing to enforce them. The first Freedom Ride left Washington, D.C., on May 4, 1961, and was scheduled to arrive in New Orleans on May 17.

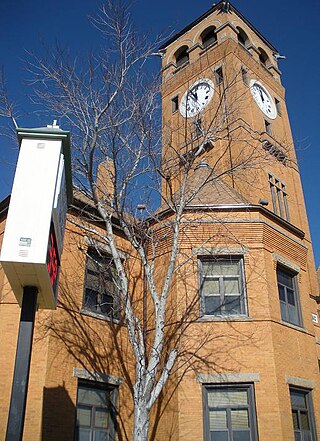

The Freedom Rides Museum is located at 210 South Court Street in Montgomery, Alabama, in the building which was until 1995 the Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station. It was the site of a violent attack on participants in the 1961 Freedom Ride during the Civil Rights Movement. The May 1961 assaults, carried out by a mob of white protesters who confronted the civil rights activists, "shocked the nation and led the Kennedy Administration to side with civil rights protesters for the first time."

Noel Francis Parrish was an American brigadier general in the United States Air Force who was the white commander of a group of black airmen known as the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II. He was a key factor in the program's success and in their units being assigned to combat duty. Parrish was born and raised in the south-east United States; he joined the U.S. Army in 1930. He served in the military from 1930 until 1964, and retired as a brigadier general in 1964.

The history of the 1954 to 1968 American civil rights movement has been depicted and documented in film, song, theater, television, and the visual arts. These presentations add to and maintain cultural awareness and understanding of the goals, tactics, and accomplishments of the people who organized and participated in this nonviolent movement.

Samuel Leamon Younge Jr. was a civil rights and voting rights activist who was murdered for trying to desegregate a "whites only" restroom. Younge was an enlisted service member in the United States Navy, where he served for two years before being medically discharged. Younge was an active member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and a leader of the Tuskegee Institute Advancement League.

The Freedom Riders National Monument is a United States National Monument in Anniston, Alabama established by President Barack Obama in January 2017 to preserve and commemorate the Freedom Riders during the Civil Rights Movement. The monument is administered by the National Park Service. The Freedom Riders National Monument is one of three National Monuments that was designated by presidential proclamation of President Obama on January 12, 2017. The second was the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument and the third, the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park, was re-designated as a National Historical Park on March 12, 2019.

Joseph D. Elsberry (April 25, 1921 – March 31, 1985) was a U.S. Army Air Force officer and a prolific African-American World War II fighter pilot in the 332nd Fighter Group's 301st Fighter Squadron, best known as the famed Tuskegee Airmen, "Red Tails," or “Schwartze Vogelmenschen” among enemy German pilots. Elsberry destroyed three enemy aircraft over France in a single mission on July 12, 1944, and a fourth aircraft in July 20, 1944, becoming the first African American fighter pilot in history to do so. He is only one of four Tuskegee Airmen to have earned three aerial victories in a single day of combat: Clarence Lester, Lee Archer (pilot), and Harry Stewart.

Harold H. Brown was a U.S. Army Air Force officer who served during World War II as a combat fighter pilot with the 332nd Fighter Group, best known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Brown's P-51C aircraft was shot down in the European Theatre of World War II and he became a prisoner of war.

Sherman Windham White Jr. †) was a U.S. Army Air Force officer and combat fighter pilot with the all-African American 332nd Fighter Group's 99th Fighter Squadron, best known as the Tuskegee Airmen.

The Alabama Black Belt National Heritage Area is a National Heritage Area encompassing Bibb, Bullock, Butler, Choctaw, Clarke, Conecuh, Dallas, Greene, Hale, Lowndes, Macon, Marengo, Monroe, Montgomery, Perry, Pickens, Sumter, Washington, and Wilcox counties in the Black Belt region of Alabama. The Center for the Study of the Black Belt at the University of West Alabama serves as the local coordinating authority.