Tenentism was a political philosophy of junior army officers who significantly contributed to the Brazilian Revolution of 1930 that ended the First Brazilian Republic.

The Ragamuffin War or Ragamuffin Revolution was a Republican uprising that began in southern Brazil, in the province of Rio Grande do Sul in 1835. The rebels were led by generals Bento Gonçalves da Silva and Antônio de Sousa Neto with the support of the Italian fighter Giuseppe Garibaldi. The war ended with an agreement between the two sides known as Green Poncho Treaty in 1845.

The Revolution of 1930 was an armed insurrection across Brazil that ended the Old Republic. The revolution replaced incumbent president Washington Luís with defeated presidential candidate and revolutionary leader Getúlio Vargas, concluding the political hegemony of a four-decade-old oligarchy and beginning the Vargas Era.

Rosário do Sul is a Brazilian municipality in the southwestern part of the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The population is 39,314 in an area of 4,369.65 km2. Its elevation is 151 m. It is located 385 km west of the state capital of Porto Alegre. Its main industry is agriculture. Many Argentine and Uruguayan tourists visits during the spring, with a large infrastructure to accommodate the visitors.

Dom Pedrito is a municipality in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. It is located at: 30° 58' 58" S 54° 40' 22" W

The Federalist Revolution was a civil war that took place in southern Brazil between 1893 and 1895, fought by the federalists, opponents of Rio Grande do Sul state president, Júlio de Castilhos, seeking greater autonomy for the state, decentralization of power by the newly installed First Brazilian Republic and, arguably, the restoration of the monarchy.

The Coluna Prestes, also known as Coluna Miguel Costa-Prestes, in English Prestes Column, was a social rebel movement that broke out in Brazil between 1924 and 1927, with links to the Tenente revolts. The rebellion's ideology was diffuse, but the main issues that caused it were the general dissatisfaction with the oligarchic First Brazilian Republic, the demand for the institution of the secret ballot, and the defense of better public education. The rebels marched some 25,000 km through the Brazilian countryside. They did not aim to defeat the forces of the Federal government in battle, but rather to ensure their survival and their ability to continue threatening the government.

The Brazilian military junta of 1930, also known as the Pacification Junta, seized power during the Revolution of 1930 and governed Brazil from 24 October to 3 November 1930, when the junta leaders handed power over to revolutionary leader Getúlio Vargas.

Isidoro Dias Lopes (30 June 1865 – 27 May 1949) was a brigadier general of the Brazilian army, often styled the "Marshal of the Revolution of 1924".

The São Paulo Revolt of 1924, also called the Revolution of 1924, Movement of 1924 or Second 5th of July was a Brazilian conflict with characteristics of a civil war, initiated by tenentist rebels to overthrow the government of president Artur Bernardes. From the city of São Paulo on 5 July, the revolt expanded to the interior of the state and inspired other uprisings across Brazil. The urban combat ended in a loyalist victory on 28 July. The rebels' withdrawal, until September, prolonged the rebellion into the Paraná Campaign.

Antônio de Siqueira Campos was a leader and one of two survivors of a military revolt that occurred in July 1922 on Copacabana Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, which became known as the Copacabana Fort revolt. Following release from prison he took part in further rebellions including the so-called Prestes Column from 1925 to 1927.

The interior of São Paulo was the scene of the São Paulo Revolt of 1924 from July, parallel to the battle for the city of São Paulo, until August and September, when the rebels left the capital and headed for the state border, first to the south of Mato Grosso and then to Paraná. There is record of revolt in 87 municipalities and support for the revolt in another 32. Local political factions joined one side or the other in the conflict, the impact of which was felt even in municipalities never traversed by the revolutionary army.

The Death Column was a military unit in the São Paulo Revolt of 1924, part of the tenentist forces in arms against the president of Brazil, Artur Bernardes. Commanded by João Cabanas, an officer of the Public Force of São Paulo, the column went on campaign on 19 July 1924, fighting loyalist forces in São Paulo and Paraná until the end of April 1925, when its commander left the revolutionary forces. Column members continued to fight as part of the Miguel Costa-Prestes Column. The denomination of "Death Column" was never official, and among the revolutionaries it was called "the battalion" or, after August 1924, the "5th Battalion of Caçadores", subordinated to the 3rd Brigade, commanded by Miguel Costa.

The Battle of Três Lagoas was an offensive by tenentist rebels against Brazilian government forces on 17–18 August 1924, extending the São Paulo Revolt into southern Mato Grosso. Led by Juarez Távora, the rebels suffered heavy losses to loyalist troops from Minas Gerais, under the command of colonel Malan d'Angrogne, in the town of Campo Japonês. This defeat frustrated the rebels' ambition to settle in Mato Grosso, forcing them to start the Paraná Campaign.

The Paraná Campaign was the continuation of the São Paulo Revolt of 1924 in western Paraná from 1924 to 1925, concluding with the formation of the Miguel Costa-Prestes Column. Rebel tenentists, led by Isidoro Dias Lopes, withdrew from São Paulo, went down the Paraná River and settled in the region from Guaíra to Foz do Iguaçu, from where they faced the forces of the Brazilian government, commanded by general Cândido Rondon from October 1924. In April 1925, another rebel column, led by Luís Carlos Prestes, arrived from Rio Grande do Sul and joined the São Paulo rebels. They entered Paraguay to escape the government siege and returned to Brazil through southern Mato Grosso, continuing their armed struggle.

The Rio Grande do Sul Revolt of 1924 was triggered by tenentist rebels from the Brazilian Army and civilian leaders from the Liberating Alliance on 28–29 October of that year. The civilians, continuing the 1923 Revolution, wanted to remove the governor of Rio Grande do Sul, Borges de Medeiros, while the military were against the president of Brazil, Artur Bernardes. After a series of defeats, in mid-November the last organized stronghold was in São Luiz Gonzaga. In the south, guerrilla warfare continued until the end of the year. From São Luiz Gonzaga, the remnants of the revolt headed out of the state, joining other rebels in the Paraná Campaign and forming the Miguel Costa-Prestes Column.

The Lightning Column was the last tenentist uprising, fought in southern Brazil from November 1926. Under the command of general Isidoro Dias Lopes, exiled in Argentina, military and civilian leaders of the government's opposition in Rio Grande do Sul combined incursions across Brazilian borders with uprisings in army garrisons in Rio Grande do Sul. The uprising, contrary to the federal and state governments, intended to indirectly support the Prestes Column, which was in Mato Grosso. Some conspirators prematurely started the revolt before the scheduled date, compromising the campaign plan, which was quickly dismantled by the loyalist army and state forces.

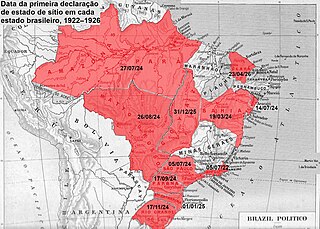

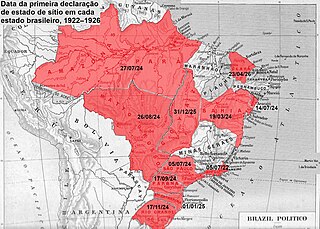

A state of emergency was in force in Brazil for much of the period from 1922 to 1927, comprising the end of president Epitácio Pessoa's government (1919–1922), most of Artur Bernardes' government (1922–1926), and the beginning of Washington Luís' government (1926–1930). The measure was decreed after the Copacabana Fort revolt, on 5 July 1922, and remained in force in several regions of Brazil's territory until the end of the subsequent tenentist revolts in February 1927, with the exception of the first months of 1924. At its peak in 1925, it was in force in the Federal District and ten states. The state of emergency allowed the political elite of the First Brazilian Republic to defend itself with authoritarian measures at a time of crisis, but the apparent tranquility after its suspension came to an end with the 1930 Revolution.

The Brazilian state of Mato Grosso was the focus of tenentist military conspiracies and the stage of a series of revolts in the 1920s: by the command of the Military Circumscription of Mato Grosso (CMMT), in Campo Grande in 1922, by the 10th Regiment of Independent Cavalry of Bela Vista in 1924, and the 17th Battalion of Caçadores of Corumbá in 1925. Tenentist forces from other states also made incursions: the column from the São Paulo Revolt, in 1924, and the Prestes Column in 1925 and again in 1926–1927. A state of emergency was in force in the state from August 1924 until the end of 1925, and again from October 1926 to February 1927.

Artur Bernardes' tenure as the 12th president of Brazil lasted from 15 November 1922, after he defeated Nilo Peçanha in the 1922 presidential election, until 15 November 1926, when he transferred power to Washington Luís. A representative of the so-called "milk coffee policy" and the last years of the First Brazilian Republic, Bernardes ruled the country almost continuously under a state of emergency, supported by the political class, rural and urban oligarchies, and high-ranking officers of the Armed Forces against a series of tenentist military revolts.