Robert Pierce Forbes (born April 27, 1958) is an American historian specializing in the politics and culture of the early American Republic, and the impact of slavery on the development of American institutions and modern society.

Robert Pierce Forbes (born April 27, 1958) is an American historian specializing in the politics and culture of the early American Republic, and the impact of slavery on the development of American institutions and modern society.

Robert Pierce Forbes was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the elder son of Henry Ashton Crosby Forbes and Grace Pierce Forbes. His childhood was spent in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he attended Shady Hill School. His father was a historian of Asian decorative arts, founder of the Captain Robert Bennet Forbes House and curator of Asian export art at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. His mother was a book editor and homemaker.[ citation needed ]

Forbes attended Concord Academy and graduated from the Cambridge High and Latin School (now Cambridge Rindge and Latin School) in 1976. He received his bachelor's degree in history from the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in 1986, receiving its Distinguished Scholar Award. After graduation he worked at the Afro-American Communities Project at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History before enrolling in the graduate program in history at Yale University, where he received a Ph.D in 1994.

From 1998 to 2006, Forbes served as the founding associate director of Yale's Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, under the directorship of David Brion Davis. During this time he also taught undergraduate and graduate courses at Yale.[ citation needed ] Between 2006 and 2014, Forbes taught U.S. history and American Studies at the University of Connecticut, Torrington. [1] Professor Forbes is also the founder of Locally Grown History, an initiative founded in 2008 to promote public history and tourism in northwest Connecticut. [2] [3] Since 2017, he has taught at Southern Connecticut State University.

In 2022, Forbes edited and annotated Notes on the State of Virginia by Thomas Jefferson (New Haven: Yale University Press), the first version to employ the original 1785 Paris edition and Jefferson's manuscript. His first book, The Missouri Compromise and its Aftermath: Slavery and the Meaning of America, the first major work on the subject in over fifty years, was described as "a profound study" by Oxford historian Daniel Walker Howe. [4] Forbes is also the author of two essays on the cultural history of slavery, "Slavery and the Evangelical Enlightenment", in McKivigan and Snay, eds., Religion and the Antebellum Debate over Slavery (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998) and "'Truth Systematised': The Changing Debate over Slavery and Abolition, 1761-1916", in McCarthy and Stauffer, eds., Prophets of Protest: Reconsidering the History of American Abolitionism (New York: The New Press, 2006).

In 2007, Forbes was an advising scholar for the PBS-documentary Prince Among Slaves .

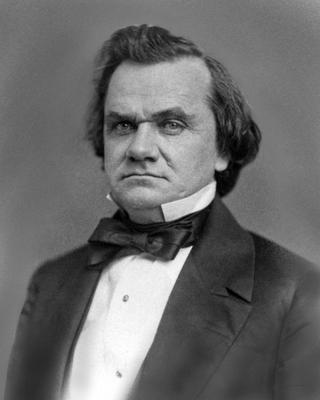

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by President Franklin Pierce. Douglas introduced the bill intending to open up new lands to develop and facilitate the construction of a transcontinental railroad. However, the Kansas–Nebraska Act effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, stoking national tensions over slavery and contributing to a series of armed conflicts known as "Bleeding Kansas."

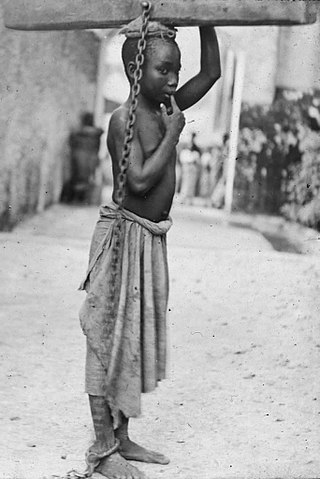

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states in the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designed by Whig senator Henry Clay and Democratic senator Stephen A. Douglas, with the support of President Millard Fillmore, the compromise centered on how to handle slavery in recently acquired territories from the Mexican–American War (1846–48).

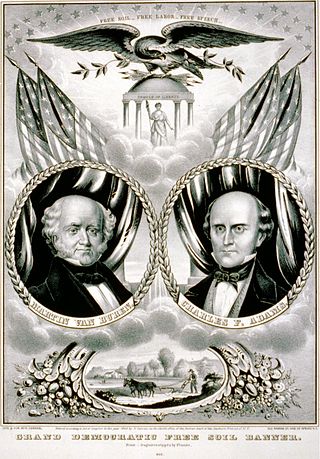

The Free Soil Party was a political party in the United States from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was focused on opposing the expansion of slavery into the western territories of the United States. The 1848 presidential election took place in the aftermath of the Mexican–American War and debates over the extension of slavery into the Mexican Cession. After the Whig Party and the Democratic Party nominated presidential candidates who were unwilling to rule out the extension of slavery into the Mexican Cession, anti-slavery Democrats and Whigs joined with members of the Liberty Party to form the new Free Soil Party. Running as the Free Soil presidential candidate, former President Martin Van Buren won 10.1 percent of the popular vote, the strongest popular vote performance by a third party up to that point in U.S. history.

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing. Involuntary servitude as a punishment for crime is still legal in the United States.

Elijah Parish Lovejoy was an American Presbyterian minister, journalist, newspaper editor, and abolitionist. After his murder by a mob, he became a martyr to the abolitionist cause opposing slavery in the United States. He was also hailed as a defender of free speech and freedom of the press.

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states to be politically imperative that the number of free states not exceed the number of slave states, so new states were admitted in slave–free pairs. There were, nonetheless, some slaves in most free states up to the 1840 census, and the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution, as implemented by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, provided that a slave did not become free by entering a free state and must be returned to their owner. Enforcement of these laws became one of the controversies which arose between slave and free states.

The history of the United States from 1849 to 1865 was dominated by the tensions that led to the American Civil War between North and South, and the bloody fighting in 1861–1865 that produced Northern victory in the war and ended slavery. At the same time industrialization and the transportation revolution changed the economics of the Northern United States and the Western United States. Heavy immigration from Western Europe shifted the center of population further to the North.

David William Blight is the Sterling Professor of History, of African American Studies, and of American Studies and Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University. Previously, Blight was a professor of History at Amherst College, where he taught for 13 years. He has won several awards, including the Bancroft Prize and Frederick Douglass Prize for Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, and the Pulitzer Prize and Lincoln Prize for Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. In 2021, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.

David Brion Davis was an American intellectual and cultural historian, and a leading authority on slavery and abolition in the Western world. He was a Sterling Professor of History at Yale University, and founder and director of Yale's Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition.

The Missouri Compromise was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state and declared a policy of prohibiting slavery in the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36°30′ parallel. The 16th United States Congress passed the legislation on March 3, 1820, and President James Monroe signed it on March 6, 1820.

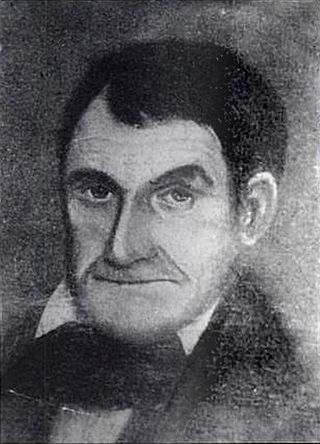

Owen Brown, father of abolitionist John Brown, was a wealthy cattle breeder and land speculator who operated a successful tannery in Hudson, Ohio. He was also a civil servant and a fervent, outspoken abolitionist. Brown was a founder of multiple institutions including the Western Reserve Anti-Slavery Society, Western Reserve College, and the Free Congressional Church. Brown gave speeches advocating the immediate abolition of slavery, and organized the Underground Railroad in the town of Hudson, Ohio.

Stephen Arnold Douglas was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A U.S. Senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party to run for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was won by Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln. Douglas had previously defeated Lincoln in the 1858 United States Senate election in Illinois, known for the pivotal Lincoln–Douglas debates. He was one of the brokers of the Compromise of 1850, which sought to avert a sectional crisis; to further deal with the volatile issue of extending slavery into the territories, Douglas became the foremost advocate of popular sovereignty, which held that each territory should be allowed to determine whether to permit slavery within its borders. This attempt to address the issue was rejected by both pro-slavery and anti-slavery advocates. Douglas was nicknamed the "Little Giant" because he was short in physical stature but a forceful and dominant figure in politics.

American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses is a book written by the American abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld, his wife Angelina Grimké, and her sister Sarah Grimké, which was published in 1839.

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery, except as punishment for a crime, through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

John Stauffer is Professor of English, American Studies, and African American Studies at Harvard University. He writes and lectures on the Civil War era, antislavery, social protest movements, and photography.

First Church in Salem is a Unitarian Universalist church in Salem, Massachusetts that was designed by Solomon Willard and built in 1836.

Commonwealth v. Aves, 35 Mass. 193 (1836), was a case in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court on the subject of transportation of slaves to free states. In August 1836, Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw ruled that slaves brought to Massachusetts "for any temporary purpose of business or pleasure" were entitled to freedom. The case was the most important legal victory for abolitionists in the 1830s and set a major precedent throughout the North.

Although the United States Constitution has never contained the words "slave" or "slavery" within its text, it dealt directly with American slavery in at least five of its provisions and indirectly protected the institution elsewhere in the document.

Michael Joseph Sugrue was an American historian and university professor. He spent his early career teaching at Columbia University and conducting research as a Mellon fellow at Johns Hopkins University prior to teaching at Princeton University, where he was the Behrman Fellow at Princeton's Council on the Humanities. After holding various positions at Princeton for over a decade, Sugrue left in 2004 to become a professor of history at Ave Maria University.