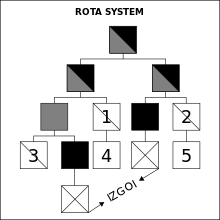

Concept

- Grey: incumbent

- Half-grey: predecessor of incumbent

- Square: male

- Black: deceased

- Diagonal: cannot be displaced

- cross: excluded or Izgoi (excluded from succession due to their parent never having held the throne)

According to the rota system concept, when the grand prince died, the next most senior prince moved to Kiev and all others moved to the principality next up the ladder. [7] [8] Only those princes whose fathers had held the throne were eligible for placement in the rota; if a man died before ascending to the throne, his sons were known as izgoi : they and their descendants were ineligible to reign. [lower-alpha 1]

The concept was first noted by Sergei Soloviev, [10] and later summed up by Vasily Kliuchevsky, [11] but in the intervening years, the structured and institutionalized rota system they presented has come under criticism by some, who doubt any such succession system to the Kievan throne existed at all. Indeed, scholars such as Sergeevich and Budovnitz argued that the seemingly endless internecine war among the princes of Kiev indicates a total lack of any established succession system. Others have modified the system but not fully abandoned it, such as A. D. Stokes, who denied that there was ever a geographic hierarchy of principalities, although there was a hierarchy of the princes themselves. [12] Janet L. B. Martin argued that the system, in fact, worked. She argues that the interprincely wars were not a breakdown or absence of a system, but the further refinement of the system as the dynasty grew in size and relations became more complex. Each new outburst of violence addressed a new problem rather than rehashing old disputes. [13] [14]

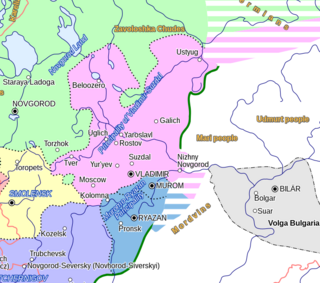

The rota system was modified by the princely summit conference held at Liubech in the Chernigov in 1097. Certain lands were granted as patrimonial lands, that is inherited lands outside the rota system. These lands were not lost by a prince when the Kievan throne became vacant, and they served as core lands that grew up into semi-independent (if not outright independent) principalities in the later centuries of Kievan Rus, leading some historians to argue that Kievan Rus ceased to be a unified state. [15] After this conference, the rota system continued to work within these patrimonial principalities at least up to the Mongol Invasion. The rota system also continued with regard to the Kievan throne after 1113 up to the Mongol Invasion as well. [16]

The rota system in some aspects survived Kievan Rus' by more than a century. Indeed, the Muscovite War of Succession (1425–1453) between Vasily II and Dmitry Shemyaka was over this very issue. Shemyaka's father, Yury of Zvenigorod, claimed that he was the rightful heir to the throne of the Principality of Vladimir through collateral succession. However, Yury's elder brother, Vasily I had passed the throne on to his son Vasily II. Dmitry and his brothers continued to press their father's and their line's claim to the throne, leading to open war between Vasily II and Shemyaka which led to Vasily's brief ouster and blinding, and Dmitry's assassination by poison in Novgorod the Great in 1453. [17] Even before the civil war though, Vasily I's father, Dmitry Donskoy, had, in fact, passed the throne on to Vasily by a will that called for linear succession rather than collateral succession, but the issue didn't come to a head until Vasily's death because he was the eldest of his generation and was thus the rightful successor by both linear and collateral succession. Thus it was only with Vasily II that the Muscovite princes were finally able to break the long-held tradition of collateral succession and establish a system of linear succession to the Muscovite throne. In doing so, they kept power in Moscow, rather than seeing it pass to other princes in other towns. [17]