The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief in England and Wales that developed out of the codification of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws in 1587–1598. The system continued until the modern welfare state emerged after the Second World War.

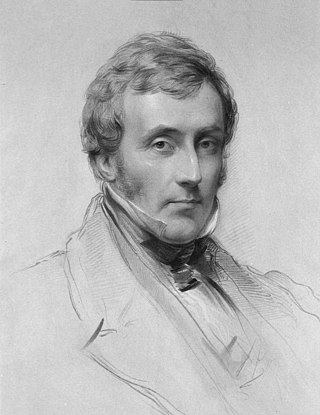

Sir Edwin Chadwick KCB was an English social reformer who is noted for his leadership in reforming the Poor Laws in England and instituting major reforms in urban sanitation and public health. A disciple of Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham, he was most active between 1832 and 1854; after that he held minor positions, and his views were largely ignored. Chadwick pioneered the use of scientific surveys to identify all phases of a complex social problem, and pioneered the use of systematic long-term inspection programmes to make sure the reforms operated as planned.

In Britain and Ireland, a workhouse was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses. The earliest known use of the term workhouse is from 1631, in an account by the mayor of Abingdon reporting that "we have erected wthn [sic] our borough a workhouse to set poorer people to work".

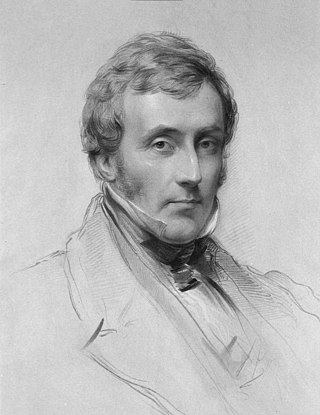

William Pulteney AlisonFRSE FRCPE FSA was a Scottish physician, social reformer and philanthropist. He was a distinguished professor of medicine at the University of Edinburgh. He served as president of the Medico-Chirurgical Society of Edinburgh (1833), president of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (1836–38), and vice-president of the British Medical Association, convening its meeting in Edinburgh in 1858.

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 (PLAA) known widely as the New Poor Law, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed by the Whig government of Earl Grey denying the right of the poor to subsistence. It completely replaced earlier legislation based on the Poor Relief Act 1601 and attempted to fundamentally change the poverty relief system in England and Wales. It resulted from the 1832 Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws, which included Edwin Chadwick, John Bird Sumner and Nassau William Senior. Chadwick was dissatisfied with the law that resulted from his report. The Act was passed two years after the Representation of the People Act 1832 which extended the franchise to middle-class men. Some historians have argued that this was a major factor in the PLAA being passed.

A poor law union was a geographical territory, and early local government unit, in Great Britain and Ireland.

The Andover workhouse scandal of the mid-1840s exposed serious defects in the administration of the English 'New Poor Law'. It led to significant changes in its central supervision and to increased parliamentary scrutiny. The scandal began with the revelation in August 1845 that inmates of the workhouse in Andover, Hampshire, England were driven by hunger to eat the marrow and gristle from bones which they were to crush to make fertilizer. The inmates' rations set by the local Poor Law guardians were less than the subsistence diet decreed by the central Poor Law Commission (PLC), and the master of the workhouse was diverting some of the funds, or the rations, for private gain. The guardians were loath to lose the services of the master, despite this and despite allegations of the master's drunkenness on duty and sexual abuse of female inmates. The commission eventually exercised its power to order dismissal of the master, after ordering two enquiries by an assistant-commissioner subject to a conflict of interest; the conduct of the second led to more public inquiry and drew criticism.

The Poor Relief Act 1601 was an Act of the Parliament of England. The Act for the Relief of the Poor 1601, popularly known as the Elizabethan Poor Law, "43rd Elizabeth" or the Old Poor Law was passed in 1601 and created a poor law system for England and Wales.

The Poor Law Commission was a body established to administer poor relief after the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. The commission was made up of three commissioners who became known as "The Bashaws of Somerset House", their secretary and nine clerks or assistant commissioners. The commission lasted until 1847 when it was replaced by a Poor Law Board – the Andover workhouse scandal being one of the reasons for this change.

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of helping the poor. Alongside ever-changing attitudes towards poverty, many methods have been attempted to answer these questions. Since the early 16th century legislation on poverty enacted by the Parliament of England, poor relief has developed from being little more than a systematic means of punishment into a complex system of government-funded support and protection, especially following the creation in the 1940s of the welfare state.

Sir Thomas Frankland Lewis, 1st Baronet was a British Poor Law Commissioner and moderate Tory MP.

From the reign of Elizabeth I until the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 relief of the poor in England was administered on the basis of a Poor Relief Act 1601. From the start of the nineteenth century the basic concept of providing poor relief was criticised as misguided by leading political economists and in southern agricultural counties the burden of poor-rates was felt to be excessive (especially where poor-rates were used to supplement low wages. Opposition to the Elizabethan Poor Law led to a Royal Commission on poor relief, which recommended that poor relief could not in the short term be abolished; however it should be curtailed, and administered on such terms that none but the desperate would claim it. Relief should only be administered in workhouses, whose inhabitants were to be confined, 'classified' and segregated. The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 allowed these changes to be implemented by a Poor Law Commission largely unaccountable to Parliament. The act was passed by large majorities in Parliament, but the regime it was intended to bring about was denounced by its critics as un-Christian, un-English, unconstitutional, and impracticable for the great manufacturing districts of Northern England. The Act itself did not introduce the regime, but introduced a framework by which it might easily be brought in.

Sir George Nicholls was a British Poor Law Commissioner after the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act. He had been an Overseer of the Poor under the old system of poor relief.

The Majority Report by the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws was published in 1909. The commission was set up by the Conservative government of Arthur Balfour to review whether the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 should be modified or changed in the way it was administered, or if new legislation should be introduced, to deal with poverty and unemployment.

The Irish poor laws were a series of acts of Parliament intended to address social instability due to widespread and persistent poverty in Ireland. While some legislation had been introduced by the pre-Union Parliament of Ireland prior to the Act of Union, the most radical and comprehensive attempt was the Irish act of 1838, closely modelled on the English Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. In England, this replaced Elizabethan era legislation which had no equivalent in Ireland.

The Scottish poor laws were the statutes concerning poor relief passed in Scotland between 1579 and 1929. Scotland had a different poor law system to England and the workings of the Scottish laws differed greatly to the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 which applied in England and Wales.

The Historiography of the Poor Laws can be said to have passed through three distinct phases. Early historiography was concerned with the deficiencies of the Old Poor Law system, later work can be characterized as an early attempt at revisionism before the writings of Mark Blaug present a truly revisionist analysis of the Poor Law system.

The following article presents a timeline of the poor law system in England from its origins in the Tudor and Elizabethan era to its abolition in 1948.

The Scottish poorhouse, occasionally referred to as a workhouse, provided accommodation for the destitute and poor in Scotland. The term poorhouse was almost invariably used to describe the institutions in that country, as unlike the regime in their workhouse counterparts in neighbouring England and Wales residents were not usually required to labour in return for their upkeep.

The Bedwellty Union Workhouse was situated in Georgetown, Tredegar. It is 2.9 miles (4.7 km) from the Nanybwtch Junction A465. The building was in existence for approximately 127 years. The workhouse building was also used as a hospital. Today, the site where the building once stood, there is a housing estate known as St James Park.