Related Research Articles

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned practice of killing a person as a punishment for a crime, usually following an authorised, rule-governed process to conclude that the person is responsible for violating norms that warrant said punishment. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in such a manner is known as a death sentence, and the act of carrying out the sentence is known as an execution. A prisoner who has been sentenced to death and awaits execution is condemned and is commonly referred to as being "on death row". Etymologically, the term capital refers to execution by beheading, but executions are carried out by many methods, including hanging, shooting, lethal injection, stoning, electrocution, and gassing.

Capital punishment in the United Kingdom predates the formation of the UK, having been used within the British Isles from ancient times until the second half of the 20th century. The last executions in the United Kingdom were by hanging, and took place in 1964; capital punishment for murder was suspended in 1965 and finally abolished in 1969. Although unused, the death penalty remained a legally defined punishment for certain offences such as treason until it was completely abolished in 1998; the last execution for treason took place in 1946. In 2004, Protocol No. 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights became binding on the United Kingdom; it prohibits the restoration of the death penalty as long as the UK is a party to the convention.

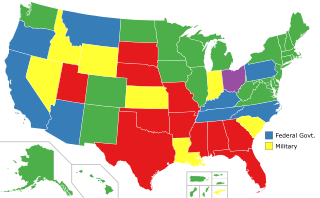

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty throughout the country at the federal level, in 27 states, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C. It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 19 states currently have the ability to execute death sentences, with the other 7, as well as the federal government and military, being subject to different types of moratoriums.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in China. It is applicable to offenses ranging from murder to drug trafficking. Executions are carried out by lethal injection or by shooting. A survey conducted by TheNew York Times in 2014 found the death penalty retained widespread support in Chinese society.

Capital punishment in India is a legal penalty for some crimes under the country's main substantive penal legislation, the Indian Penal Code, as well as other laws. Executions are carried out by hanging as the primary method of execution per Section 354(5) of the Criminal Code of Procedure, 1973 is "Hanging by the neck until dead", and is imposed only in the 'rarest of cases'.

Capital punishment – the process of sentencing convicted offenders to death for the most serious crimes and carrying out that sentence, as ordered by a legal system – first appeared in New Zealand in a codified form when New Zealand became a British colony in 1840. It was first carried out with a public hanging in Victoria Street, Auckland in 1842, while the last execution occurred in 1957 at Mount Eden Prison, also in Auckland. In total, 85 people have been lawfully executed in New Zealand.

Capital punishment in Denmark was abolished in 1933, with no death sentences having been carried out since 1892, but restored from 1945 to 1950 in order to execute Nazi collaborators. Capital punishment for most instances of war crimes was abolished in 1978. The last execution was carried out in June 1950.

The Homicide Act 1957 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was enacted as a partial reform of the common law offence of murder in English law by abolishing the doctrine of constructive malice, reforming the partial defence of provocation, and by introducing the partial defences of diminished responsibility and suicide pact. It restricted the use of the death penalty for murder.

Capital punishment in Sweden was last used in 1910, though it remained a legal sentence for at least some crimes until 1973. It is now outlawed by the Swedish Constitution, which states that capital punishment, corporal punishment, and torture are strictly prohibited. At the time of the abolition of the death penalty in Sweden, the legal method of execution was beheading. It was one of the last states in Europe to abolish the death penalty.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Russia, but is not used due to a moratorium and no death sentences or executions have been carried out since 2 August 1996. Russia has had an implicit moratorium in place since one was established by President Boris Yeltsin in 1996, and explicitly established by the Constitutional Court of Russia in 1999 and reaffirmed in 2009.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Pakistan. Although there have been numerous amendments to the Constitution, there is yet to be a provision prohibiting the death penalty as a punitive remedy.

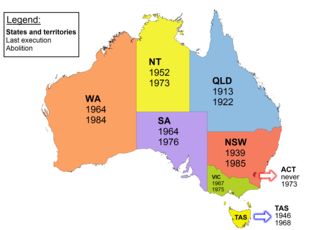

Capital punishment in Australia has been abolished in all jurisdictions since 1985. Queensland abolished the death penalty in 1922. Tasmania did the same in 1968. The Commonwealth abolished the death penalty in 1973, with application also in the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. Victoria did so in 1975, South Australia in 1976, and Western Australia in 1984. New South Wales abolished the death penalty for murder in 1955, and for all crimes in 1985. In 2010, the Commonwealth Parliament passed legislation prohibiting the re-establishment of capital punishment by any state or territory. Australian law prohibits the extradition or deportation of a prisoner to another jurisdiction if they could be sentenced to death for any crime.

Capital punishment in Armenia was a method of punishment that was implemented within Armenia's Criminal Code and Constitution until its eventual relinquishment in the 2003 modifications made to the Constitution. Capital punishment's origin in Armenia is unknown, yet it remained present in the Armenia Criminal Code of 1961, which was enforced and applied until 1999. Capital punishment was incorporated into Armenian legislation and effectuated for capital crimes, which were crimes that were classified to be punishable by death, including treason, espionage, first-degree murder, acts of terrorism and grave military crimes.

Capital punishment in Georgia was completely abolished on 1 May 2000 when the country signed Protocol 6 to the ECHR. Later Georgia also adopted the Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR. Capital punishment was replaced with life imprisonment.

Capital punishment in the Republic of Ireland was abolished in statute law in 1990, having been abolished in 1964 for most offences including ordinary murder. The last person to be executed by the British state on the island of Ireland was Robert McGladdery, who was hanged on 20 December 1961 in Crumlin Road Gaol in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The last person to be executed by the state in the Republic of Ireland was Michael Manning, hanged for murder on 20 April 1954. All subsequent death sentences in the Republic of Ireland, the last handed down in 1985, were commuted by the President, on the advice of the Government, to terms of imprisonment of up to 40 years. The Twenty-first Amendment to the constitution, passed by referendum in 2001, prohibits the reintroduction of the death penalty, even during a state of emergency or war. Capital punishment is also forbidden by several human rights treaties to which the state is a party.

The debate over capital punishment in the United States existed as early as the colonial period. As of April 2022, it remains a legal penalty within 28 states, the federal government, and military criminal justice systems. The states of Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, New Hampshire, Virginia, and Washington abolished the death penalty within the last decade alone.

Capital punishment in Lithuania was ruled unconstitutional and abolished for all crimes on 9 December 1998. Lithuania is a member of the Council of Europe and has signed and ratified Protocol 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights on complete abolition of death penalty. From March 1990 to December 1998, Lithuania executed seven people, all men. The last execution in the country occurred in July 1995, when Lithuanian mafia boss Boris Dekanidze was executed.

Capital punishment in Sudan is legal under Article 27 of the Sudanese Criminal Act 1991. The Act is based on Sharia law which prescribes both the death penalty and corporal punishment, such as amputation. Sudan has moderate execution rates, ranking 8th overall in 2014 when compared to other countries that still continue the practice, after at least 29 executions were reported.

Capital punishment in Malawi is a legal punishment for certain crimes. The country abolished the death penalty following a Malawian Supreme Court ruling in 2021, but it was soon reinstated. However, the country is currently under a death penalty moratorium, which has been in place since the latest execution in 1992.

Capital punishment in Burkina Faso has been abolished. In late May 2018, the National Assembly of Burkina Faso adopted a new penal code that omitted the death penalty as a sentencing option, thereby abolishing the death penalty for all crimes.

References

Sources

- Royal Commission on Capital Punishment (1866). Report, together with the minutes of evidence and appendix. Parliamentary Papers. Vol. HC 1866 (3590) xxi 1. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

Citations

- ↑ "Punishment Of Death.—Select Committee Moved For". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard) . 3 May 1864. cc2055-115. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ↑ "Capital Punishment". Pall Mall Gazette . No. 275. 26 December 1865. p. 6.