A loom is a device used to weave cloth and tapestry. The basic purpose of any loom is to hold the warp threads under tension to facilitate the interweaving of the weft threads. The precise shape of the loom and its mechanics may vary, but the basic function is the same.

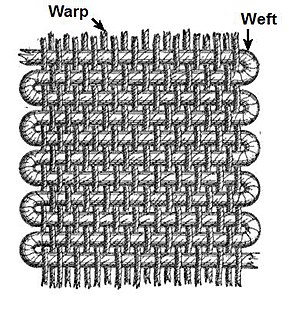

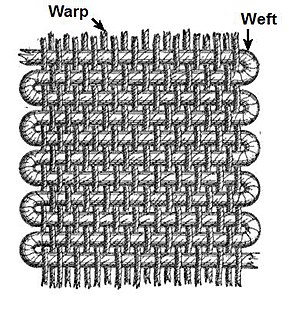

Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal threads are called the warp and the lateral threads are the weft, woof, or filling. The method in which these threads are inter-woven affects the characteristics of the cloth. Cloth is usually woven on a loom, a device that holds the warp threads in place while filling threads are woven through them. A fabric band that meets this definition of cloth can also be made using other methods, including tablet weaving, back strap loom, or other techniques that can be done without looms.

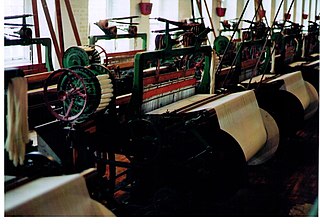

A power loom is a mechanized loom, and was one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. The first power loom was designed in 1786 by Edmund Cartwright and first built that same year. It was refined over the next 47 years until a design by the Howard and Bullough company made the operation completely automatic. This device was designed in 1834 by James Bullough and William Kenworthy, and was named the Lancashire loom.

Warp and weft are the two basic components used in weaving to turn thread or yarn into fabric. The lengthwise or longitudinal warp yarns are held stationary in tension on a frame or loom while the transverse weft is drawn through and inserted over and under the warp. A single thread of the weft crossing the warp is called a pick. Terms vary. Each individual warp thread in a fabric is called a warp end or end.

Saliyar or Saliya or Chaliyan or Sali or Sale is an Indian caste. Their traditional occupation was that of weaving and they are found mostly in the regions of northern Kerala, southern coastal Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

From the reign of Elizabeth I until the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834 relief of the poor in England was administered on the basis of a Poor Law enacted in 1601. From the start of the nineteenth century the basic concept of providing poor relief was criticised as misguided by leading political economists and in southern agricultural counties the burden of poor-rates was felt to be excessive (especially where poor-rates were used to supplement low wages. Opposition to the Elizabethan Poor Law led to a Royal Commission on poor relief, which recommended that poor relief could not in the short term be abolished; however it should be curtailed, and administered on such terms that none but the desperate would claim it. Relief should only be administered in workhouses, whose inhabitants were to be confined, 'classified' and segregated. The Poor Law Amendment Act allowed these changes to be implemented by a Poor Law Commission largely unaccountable to Parliament. The Act was passed by large majorities in Parliament, but the regime it was intended to bring about was denounced by its critics as un-Christian, un-English, unconstitutional, and impracticable for the great manufacturing districts of Northern England. The Act itself did not introduce the regime, but introduced a framework by which it might easily be brought in.

Sir Edward James Harland, 1st Baronet, was an Ulster-based English shipbuilder and politician. Born in Scarborough in the North Riding of Yorkshire, he was educated at Edinburgh Academy. In 1846, aged 15, he took an apprenticeship at the engineering works of Robert Stephenson and Company in Newcastle upon Tyne. Afterwards he was employed in jobs in Glasgow and again in Newcastle, before moving to Belfast in 1854 to manage Robert Hickson's shipyard at Queen's Island. Four years later he bought the yard and renamed the business Edward James Harland and Company. In 1861 he formed a business partnership with Gustav Wilhelm Wolff, his former personal assistant, creating Harland and Wolff. Later, Harland recruited William James Pirrie as another partner. Edward Harland, Gustav Wolff and William James Pirrie maintained a successful business, receiving regular orders from the White Star Line, before Harland's retirement in 1889, leaving Wolff and Pirrie to manage the shipyard.

A weavers' cottage was a type of house used by weavers for cloth production in the putting-out system sometimes known as the domestic system.

The Lancashire Loom was a semi-automatic power loom invented by James Bullough and William Kenworthy in 1842. Although it is self-acting, it has to be stopped to recharge empty shuttles. It was the mainstay of the Lancashire cotton industry for a century.

A weaving shed is a distinctive type of mill developed in the early 1800s in Lancashire, Derbyshire and Yorkshire to accommodate the new power looms weaving cotton, silk, woollen and worsted. A weaving shed can be a stand-alone mill, or a component of a combined mill. Power looms cause severe vibrations requiring them to be located on a solid ground floor. In the case of cotton, the weaving shed needs to remain moist. Maximum daylight is achieved, by the sawtooth "north-facing roof lights".

Harle Syke mill is a weaving shed in Briercliffe on the outskirts of Burnley, Lancashire. It was built on a green field site in 1856, together with terraced houses for the workers. These formed the nucleus of the community of Harle Syke. The village expanded and six other mills were built, including Queen Street Mill.

Thomas Coxe (1615–1685) was an English physician. He studied at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, graduating with a BA in 1635 and an MA in 1638. He was among the initial fellows of the Royal Society, but ran into money difficulties in old age.

The history of the textile arts of Bangladesh dates back to the 1st century AD. According to the archaeological excavations, Bangladesh was once famous for its artistic textile production throughout the world. Over the years, several types of textiles evolved in the country, mostly by the indigenous handloom manufacturers.

William Horrocks, a cotton manufacturer of Stockport built an early power loom in 1803, based on the principles of Cartwright but including some significant improvements to cloth take up and in 1813 battening.

Jelinger Cookson Symons was an English barrister, school inspector and writer.

A Dandy loom was a hand loom, that automatically ratchetted the take-up beam. Each time the weaver moved the sley to beat-up the weft, a rachet and pawl mechanism advanced the cloth roller. In 1802 William Ratcliffe of Stockport patented a Dandy loom with a cast-iron frame. It was this type of Dandy loom that was used in the small dandy loom shops.

The Great Writers series was a collection of literary biographies published in London from 1887, by Walter Scott & Co. The founding editor was Eric Sutherland Robertson, followed by Frank T. Marzials.

Padmanabhan Gopinathan is an Indian master weaver of handloom textiles and the founder of Eco Tex Handloom Consortium, an organization promoting handloom weaving in Manjavilakom, a small hamlet in Thiruvananthapuram, in the south Indian state of Kerala. Under the aegis of the organization, he provides employment to over 1800 women in the village. The Government of India awarded him the fourth highest civilian honour of the Padma Shri, in 2007, for his social commitment and his contributions to the art of weaving.

John Bethune (1812–1839) was a short-lived Scottish weaver-poet. He sometimes wrote under the pen-name of the Fifeshire Forester.