Related Research Articles

A dragon is a large magical legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as winged, horned, and capable of breathing fire. Dragons in eastern cultures are usually depicted as wingless, four-legged, serpentine creatures with above-average intelligence. Commonalities between dragons' traits are often a hybridization of feline, reptilian, mammal, and avian features. Scholars believe vast extinct or migrating crocodiles bear the closest resemblance, especially when encountered in forested or swampy areas, and are most likely the template of modern Oriental dragon imagery.

The serpent, or snake, is one of the oldest and most widespread mythological symbols. The word is derived from Latin serpens, a crawling animal or snake. Snakes have been associated with some of the oldest rituals known to humankind and represent dual expression of good and evil.

In Ancient Greek kētŏs, Latinized as cetus, is any huge sea monster. According to the mythology, Perseus slew a cetus to save Andromeda from being sacrificed to it. The term cetacean derives from cetus. In Greek art, ceti were depicted as serpentine fish. The name of the mythological figure Ceto is derived from kētos. The name of the constellation Cetus also derives from this word.

In Greek mythology, Phorcys or Phorcus is a primordial sea god, generally cited as the son of Pontus and Gaia (Earth). Classical scholar Karl Kerenyi conflated Phorcys with the similar sea gods Nereus and Proteus. His wife was Ceto, and he is most notable in myth for fathering by Ceto a host of monstrous children. In extant Hellenistic-Roman mosaics, Phorcys was depicted as a fish-tailed merman with crab-claw legs and red, spiky skin.

Mormo was a female spirit in Greek folklore, whose name was invoked by mothers and nurses to frighten children to keep them from misbehaving.

In Greek mythology, Python was the serpent, sometimes represented as a medieval-style dragon, living at the center of the earth, believed by the ancient Greeks to be at Delphi.

The Lernaean Hydra or Hydra of Lerna, more often known simply as the Hydra, is a serpentine water monster in Greek and Roman mythology. Its lair was the lake of Lerna in the Argolid, which was also the site of the myth of the Danaïdes. Lerna was reputed to be an entrance to the Underworld, and archaeology has established it as a sacred site older than Mycenaean Argos. In the canonical Hydra myth, the monster is killed by Heracles (Hercules) as the second of his Twelve Labors.

In Norse mythology, Garmr or Garm is a wolf or dog associated with both Hel and Ragnarök, and described as a blood-stained guardian of Hel's gate.

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it on 1 November 1950 in his apostolic constitution Munificentissimus Deus as follows:

We proclaim and define it to be a dogma revealed by God that the immaculate Mother of God, Mary ever virgin, when the course of her earthly life was finished, was taken up body and soul into the glory of heaven.

The Dormition of the Mother of God is a Great Feast of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Catholic Churches. It celebrates the "falling asleep" (death) of Mary the Theotokos, and her being taken up into heaven. It is celebrated on 15 August as the Feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God. The Armenian Apostolic Church celebrates the Dormition not on a fixed date, but on the Sunday nearest 15 August. In Western Churches the corresponding feast is known as the Assumption of Mary, with the exception of the Scottish Episcopal Church, which has traditionally celebrated the Falling Asleep of the Blessed Virgin Mary on 15 August.

Agathos Daimon originally was a lesser deity (daemon) of classical ancient Greek religion and Graeco-Egyptian religion. In his original Greek form, he served as a household god, to whom, along with Zeus Soter, libations were made after a meal. In later (post-)Ptolemaic antiquity he took on two partially distinct roles; one as the Agathos Daimon a prominent serpentine civic god, who served as the special protector of Alexandria. The other as a genus of serpentine household gods, the Agathoi Daimones, individual protectors of the homes in which they were worshipped.

An Instinct for Dragons is a book by University of Central Florida anthropologist, David E. Jones, in which he seeks to explain the universality of dragon images in the folklore of human societies. In the introduction, Jones conducts a survey of dragon myths from cultures around the world and argues that certain aspects of dragons or dragon-like mythical creatures are found very widely. He claims that even the Inuit have a reptilian dragon-like monster, even though they had never seen an actual reptile.

Ladon was a monster in Greek mythology, the dragon that guarded the golden apples in the Garden of the Hesperides.

Dragons play a significant role in Greek mythology. Though the Greek drakōn often differs from the modern Western conception of a dragon, it is both the etymological origin of the modern term and the source of many surviving Indo-European myths and legends about dragons.

Snakes are a common occurrence in myths for a multitude of cultures. The Hopi people of North America viewed snakes as symbols of healing, transformation, and fertility. In other cultures snakes symbolized the umbilical cord, joining all humans to Mother Earth. The Great Goddess often had snakes as her familiars—sometimes twining around her sacred staff, as in ancient Crete—and they were worshipped as guardians of her mysteries of birth and regeneration. Although not entirely a snake, the plumed serpent, Quetzalcoatl, in Mesoamerican culture, particularly Mayan and Aztec, held a multitude of roles as a deity. He was viewed as a twin entity which embodied that of god and man and equally man and serpent, yet was closely associated with fertility. In ancient Aztec mythology, Quetzalcoatl was the son of the fertility earth goddess, Cihuacoatl, and cloud serpent and hunting god, Maxicoat. His roles took the form of everything from bringer of morning winds and bright daylight for healthy crops, to a sea god capable of bringing on great floods. As shown in the images there are images of the sky serpent with its tail in its mouth, it is believed to be a reverence to the sun, for which Quetzalcoatl was also closely linked.

In Greek mythology, Delphyne is the name given, by some accounts, to the monstrous serpent killed by Apollo at Delphi. Although, in Hellenistic and later accounts, the Delphic monster slain by Apollo is usually said to be the male serpent Python, in the earliest known account of this story, the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, the god kills a nameless she-serpent (drakaina), subsequently called Delphyne. According to the Suda, Delphi was named after Delphyne.

In Greek mythology, a drakaina is a female serpent or dragon, sometimes with humanlike features.

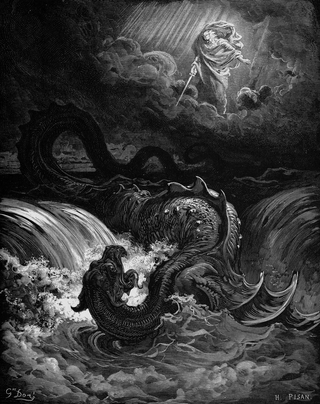

Lotan, also transliterated Lôtān, Litan, or Litānu, is a servant of the sea god Yam defeated by the storm god Hadad-Baʿal in the Ugaritic Baal Cycle. Lotan seems to have been prefigured by the serpent Têmtum represented in Syrian seals of the 18th–16th century BC, and finds a later reflex in the sea monster Leviathan, whose defeat at the hands of Yahweh is alluded to in the biblical Book of Job and in Isaiah 27:1. Lambert (2003) went as far as the claim that Isaiah 27:1 is a direct quote lifted from the Ugaritic text, correctly rendering Ugaritic bṯn "snake" as Hebrew nḥš "snake".

Psamathe, sometimes given only as the daughter of Crotopus, was the daughter of King Crotopus of Argos, who became the lover of the god Apollo.

Aratus was in Greek mythology the son of the god Asclepius and the mortal Sicyonian woman Aristodeme. He was half-brother to Aceso, Aegle, Hygieia, Iaso, Meditrina, Panacea, Machaon, Podalirius, and Telesphoros.

References

- 1 2 3 Ogden, Daniel (2013). Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford UP. p. 378. ISBN 9780199557325.