Early modern human (EMH), or anatomically modern human (AMH), are terms used to distinguish Homo sapiens that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans, from extinct archaic human species. This distinction is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, for example, in Paleolithic Europe. Among the oldest known remains of Homo sapiens are those found at the Omo-Kibish I archaeological site in south-western Ethiopia, dating to about 233,000 to 196,000 years ago, the Florisbad site in South Africa, dating to about 259,000 years ago, and the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco, dated about 315,000 years ago.

The lumbar vertebrae are located between the thoracic vertebrae and pelvis. They form the lower part of the human back in humans, and the tail end of the back in quadrupeds. In humans, there are five lumbar vertebrae. The term is used to describe the anatomy of humans and quadrupeds, such as horses, pigs, or cattle. These bones are found in particular cuts of meat, including tenderloin or sirloin steak.

Homo heidelbergensis is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human which existed during the Middle Pleistocene. It was subsumed as a subspecies of H. erectus in 1950 as H. e. heidelbergensis, but towards the end of the century, it was more widely classified as its own species. It is debated whether or not to constrain H. heidelbergensis to only Europe or to also include African and Asian specimens, and this is further confounded by the type specimen being a jawbone, because jawbones feature few diagnostic traits and are generally missing among Middle Pleistocene specimens. Thus, it is debated if some of these specimens could be split off into their own species or a subspecies of H. erectus. Because the classification is so disputed, the Middle Pleistocene is often called the "muddle in the middle".

Homo rhodesiensis is the species name proposed by Arthur Smith Woodward (1921) to classify Kabwe 1, a Middle Stone Age fossil recovered from Broken Hill mine in Kabwe, Northern Rhodesia. In 2020, the skull was dated to 324,000 to 274,000 years ago. Other similar older specimens also exist.

An occipital bun, also called an occipital spur, occipital knob, chignon hook or inion hook, is a prominent bulge or projection of the occipital bone at the back of the skull. It is important in scientific descriptions of classic Neanderthal crania. It is found among archaic Homo species, as well as Upper Pleistocene Homo sapiens and present-day human populations.

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are exceptionally strong jaw muscles. The sagittal crest serves primarily for attachment of the temporalis muscle, which is one of the main chewing muscles. Development of the sagittal crest is thought to be connected to the development of this muscle. A sagittal crest usually develops during the juvenile stage of an animal in conjunction with the growth of the temporalis muscle, as a result of convergence and gradual heightening of the temporal lines.

The crown is the top portion of the head behind the vertex. The anatomy of the crown varies between different organisms. The human crown is made of three layers of the scalp above the skull. The crown also covers a range of bone sutures, and contains blood vessels and branches of the trigeminal nerve.

Maba Man is a pre-modern hominin whose remains were discovered in 1958 in caves near the town called Maba, near Shaoguan city in the northern part of Guangdong province, China.

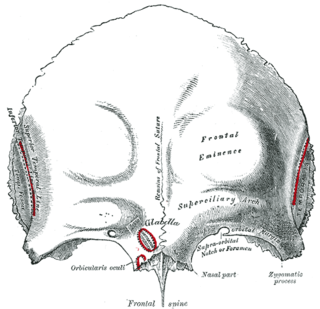

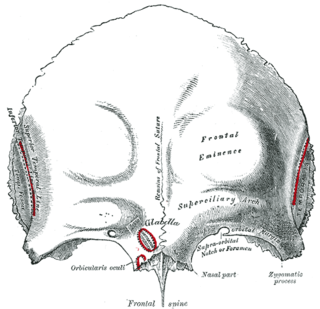

The brow ridge, or supraorbital ridge known as superciliary arch in medicine, is a bony ridge located above the eye sockets of all primates and some other animals. In humans, the eyebrows are located on their lower margin.

Archaic humans is a broad category denoting all species of the genus Homo that are not Homo sapiens. Among the earliest modern human remains are those from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, Florisbad in South Africa (259 ka), Omo-Kibish I in southern Ethiopia, and Apidima Cave in Southern Greece. Some examples of archaic humans include H. antecessor (1200–770 ka), H. bodoensis (1200–300 ka), H. heidelbergensis (600–200 ka), Neanderthals, H. rhodesiensis (300–125 ka) and Denisovans.

KNM ER 406 is an almost complete fossilized skull of the species Paranthropus boisei. It was discovered in Koobi Fora, Kenya by Richard Leakey and H. Mutua in 1969. This species is grouped with the Australopitecine genus, Paranthropus boisei because of the robusticity of the skull and the prominent characteristics. This species was found well preserved with a complete cranium but lacking dentition. He was known for his robust cranial features that showed the signs of adaptation of the ecological niches. The big chewing muscles attached to the sagittal crest are traits of this adaptation.

In physical anthropology, post-orbital constriction is the narrowing of the cranium (skull) just behind the eye sockets found in most non-human primates and early hominins. This constriction is very noticeable in non-human primates, slightly less so in Australopithecines, even less in Homo erectus and completely disappears in modern Homo sapiens. Post-orbital constriction index in non-human primates and hominin range in category from increased constriction, intermediate, reduced constriction and disappearance. The post-orbital constriction index is defined by either a ratio of minimum frontal breadth (MFB), behind the supraorbital torus, divided by the maximum upper facial breadth (BFM), bifrontomalare temporale, or as the maximum width behind the orbit of the skull.

Dali man is the remains of a late Homo erectus or archaic Homo sapiens who lived in the late-mid Pleistocene epoch. The remains comprise a complete fossilized skull, which was discovered by Liu Shuntang in 1978 in Dali County, Shaanxi Province, China.

The endocranium in comparative anatomy is a part of the skull base in vertebrates and it represents the basal, inner part of the cranium. The term is also applied to the outer layer of the dura mater in human anatomy.

Homo erectus is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Its specimens are among the first recognizable members of the genus Homo.

Neanderthal anatomy differed from modern humans in that they had a more robust build and distinctive morphological features, especially on the cranium, which gradually accumulated more derived aspects, particularly in certain isolated geographic regions. This robust build was an effective adaptation for Neanderthals, as they lived in the cold environments of Europe. In which they also had to operate in Europe's dense forest landscape that was extremely different from the environments of the African grassland plains that Homo sapiens adapted to with a different anatomical build.

Muscular evolution in humans is an overview of the muscular adaptations made by humans from their early ancestors to the modern man. Humans are believed to be predisposed to develop muscle density as early humans depended on muscle structures to hunt and survive. Modern man's need for muscle is not as dire, but muscle development is still just as rapid if not faster due to new muscle building techniques and knowledge of the human body.

The Ndutu skull is the partial cranium of a hominin that has been assigned variously to late Homo erectus, Homo rhodesiensis, and early Homo sapiens, from the Middle Pleistocene, found at Lake Ndutu in northern Tanzania.

Chancelade man is an ancient anatomically modern human fossil of a male found in Chancelade in France in 1888. The skeleton was that of a rather short man, who stood a mere 1.55 m (5.1 ft) tall.

Homo naledi is an extinct species of archaic human discovered in 2013 in the Rising Star Cave system, Gauteng province, South Africa, dating to the Middle Pleistocene 335,000–236,000 years ago. The initial discovery comprises 1,550 specimens of bone, representing 737 different skeletal elements, and at least 15 different individuals. Despite this exceptionally high number of specimens, their classification with other Homo species remains unclear.