Related Research Articles

The Supreme Court of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, known locally as the Stera Mahkama, is the court of last resort of Afghanistan. Under the current Taliban government, the court has no independence or power of judicial review; the supreme leader of Afghanistan holds the ultimate authority to decide and interpret the law and may overturn any decision of any court. The current chief justice is Abdul Hakim Haqqani.

Mohammed Younus Shaikh is a Pakistani medical doctor, human rights activist and freethinker.

Fazal Hadi Shinwari was an Afghan cleric who served as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Afghanistan from 2002 until 2006. He was appointed to the post by Afghan President Hamid Karzai in 8 January 2002 in accordance with the Afghan Constitution approved after the 2001 overthrow of the Taliban government. An ethnic Pashtun from Jalalabad, Afghanistan, he was a member of the Ittehad-al-Islami party. Shinwari died in February 2011 from stroke.

Since the establishment of the Taliban-led government in 2021, Afghanistan has been widely considered to have one of the worst human rights records in the world. In 2022, Freedom House rated Afghanistan's freedom as 10 out of 100.

Abdul Rahman is an Afghan man whose arrest and trial in February 2006 sparked widespread controversy among the international community. Rahman had been arrested by Afghan authorities for apostasy and subsequently threatened with the death penalty. He had converted to Christianity from Islam while providing medical assistance to Afghan refugees in Peshawar, Pakistan. On 26 March 2006, under heavy pressure from foreign governments, the Afghan court returned his case to prosecutors, citing "investigative gaps"; Rahman was released from prison and remanded to his family on the night of 27 March. On 29 March, Abdul Rahman arrived in Italy after being offered asylum by the Italian government. Representatives within the Afghan government and many Afghan citizens continued to call for Rahman's execution, and his wife divorced him shortly after his conversion, leading to an unsuccessful custody battle for their two children.

In 2022, Freedom House rated Pakistan’s human rights at 37 out 100.

Capital punishment is a legal punishment in Iran. Crimes punishable by death include murder; rape; child molestation; homosexuality; pedophilia; drug trafficking; armed robbery; kidnapping; terrorism; burglary; incestuous relationships; fornication; prohibited sexual relations; sodomy; sexual misconduct; prostitution; plotting to overthrow the Islamic regime; political dissidence; sabotage; arson; rebellion; apostasy; adultery; blasphemy; extortion; counterfeiting; smuggling; speculating; disrupting production; recidivist consumption of alcohol; producing or preparing food, drink, cosmetics, or sanitary items that lead to death when consumed or used; producing and publishing pornography; using pornographic materials to solicit sex; recidivist false accusation of capital sexual offenses causing execution of an innocent person; recidivist theft; certain military offenses ; "waging war against God"; "spreading corruption on Earth"; espionage; and treason. Iran carried out at least 977 executions in 2015, at least 567 executions in 2016, and at least 507 executions in 2017. In 2018 there were at least 249 executions, at least 273 in 2019, at least 246 in 2020, at least 290 in 2021, at least 553 in 2022, and at least 309 so far in 2023.

The Pakistan Penal Code, the main criminal code of Pakistan, penalizes blasphemy against any recognized religion, providing penalties ranging from a fine to death. According to human rights groups, blasphemy laws in Pakistan have been exploited not so much for protecting religious sensibilities of Muslims, but for persecuting minorities, and for settling personal rivalries -- often against other Muslims.

Iran is a constitutional, Islamic theocracy. Its official religion is the doctrine of the Twelver Jaafari School. Iran's law against blasphemy derives from Sharia. Blasphemers are usually charged with "spreading corruption on earth", or mofsed-e-filarz, which can also be applied to criminal or political crimes. The law against blasphemy complements laws against criticizing the Islamic regime, insulting Islam, and publishing materials that deviate from Islamic standards.

In Islam, blasphemy is impious utterance or action concerning God, but is broader than in normal English usage, including not only the mocking or vilifying of attributes of Islam but denying any of the fundamental beliefs of the religion. Examples include denying that the Quran was divinely revealed, the Prophethood of one of the Islamic prophets, insulting an angel, or maintaining God had a son.

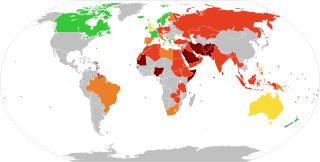

A blasphemy law is a law prohibiting blasphemy, which is the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence to a deity, or sacred objects, or toward something considered sacred or inviolable. According to Pew Research Center, about a quarter of the world's countries and territories (26%) had anti-blasphemy laws or policies as of 2014.

Saudi Arabia's laws are an amalgam of rules from Sharia, royal decrees, royal ordinances, other royal codes and bylaws, fatwas from the Council of Senior Scholars and custom and practice.

A person who is accused of blasphemy in Yemen is often subject to vigilantism by governmental authorities. An accused person is subject to Sharia, which, according to some interpretations, prescribes death for blasphemy.

Afghanistan uses Sharia as its justification for punishing blasphemy. The punishments are among the harshest in the world. Afghanistan uses its law against blasphemy to persecute religious minorities, apostasy, dissenters, academics, and journalists.

The main blasphemy law in Egypt is Article 98(f) of the Egyptian Penal Code. It penalizes: "whoever exploits and uses the religion in advocating and propagating by talk or in writing, or by any other method, extremist thoughts with the aim of instigating sedition and division or disdaining and contempting any of the heavenly religions or the sects belonging thereto, or prejudicing national unity or social peace."

Jerome Starkey is an English journalist, broadcaster and author best known for covering wars and the environment. He challenged US forces over civilian casualties in Afghanistan and was deported from Kenya in 2017 after reporting on state-sponsored corruption and extrajudicial killings.

Ethiopian judicial authority v Swedish journalists 2011 was about the legal proceedings relating to claims that Swedish journalists Johan Persson and Martin Schibbye were supporting terrorism in Ethiopia. Relations between Sweden and Ethiopia were seriously affected by this case. In 2011, Ethiopia was claimed to detain more than 150 innocent people, including reporters. Johan Persson and Martin Schibbye were released in September 2012 as part of a mass pardon, and returned home to Sweden.

Mohamed Cheikh Ould Mkhaitir is a Mauritanian blogger who was a political prisoner from 2014 to 2019. He was sentenced to death after he wrote an article critical of Islam and the caste system in Mauritania, after which he became a designated prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International. He now lives in exile in France due to concerns for his safety.

Kambakhsh is a surname that may refer to:

The situation for apostates from Islam varies markedly between Muslim-minority and Muslim-majority regions. In Muslim-minority countries, "any violence against those who abandon Islam is already illegal". But in some Muslim-majority countries, religious violence is "institutionalised", and "hundreds and thousands of closet apostates" live in fear of violence and are compelled to live lives of "extreme duplicity and mental stress."

References

- 1 2 Mineeia, Zainab (21 October 2008). "Afghanistan: Journalist Serving 20 Years for "Blasphemy"". IPS (Inter Press Service). Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ↑ Wiseman, Paul (31 January 2008). "Afghan student's death sentence hits nerve". USA Today. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- 1 2 "2008 Report on International Religious Freedom - Afghanistan". United States Department of State. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ↑ Sengupta, Kim; Jerome Starkey (2 February 2008). "Lifeline for Pervez: Afghan Senate withdraws demand for death sentence". The Independent. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- 1 2 Adams, Brad (10 March 2009). "Afghanistan: 20-Year Sentence for Journalist Upheld". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ↑ Sengupta, Kim (7 September 2009). "Free at last: Student in hiding after Karzai's intervention". The Independent. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ↑ Svensson, Niklas (22 January 2015). "Carl Bildt räddade livet på dödsdömd student". Expressen. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ "Afghan student 'escaped' on secret Swedish plane". The Local Sweden. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2017.