Hissène Habré, also spelled Hissen Habré, was a Chadian politician and convicted war criminal who served as the 5th president of Chad from 1982 until he was deposed in 1990.

The SIAI-Marchetti SF.260 is an Italian light aircraft which has been commonly marketed as a military trainer and aerobatics aircraft.

Goukouni Oueddei is a Chadian politician who served as President of Chad from 1979 to 1982.

FROLINAT was an insurgent rebel group active in Chad between 1966 and 1993.

The Chadian Air Force is the aviation branch of the Chad National Army. It was formed in 1961 as the Chadian National Flight/Squadron.

The 1975 coup d'état in Chad that terminated Tombalbaye's government received an enthusiastic response in the capital N'Djamena. Félix Malloum emerged as the chairman of the new Supreme Military Council, and the first days of the new regime were celebrated as many political prisoners were released. His government included more Muslims from northern and eastern Chad, but ethnic and regional dominance still remained very much in the hands of southerners.

The Transitional Government of National Unity was the coalition government of armed groups that nominally ruled Chad from 1979 to 1982, during the most chaotic phase of the long-running civil war that began in 1965. The GUNT replaced the fragile alliance led by Félix Malloum and Hissène Habré, which collapsed in February 1979. GUNT was characterized by intense rivalries that led to armed confrontations and Libyan intervention in 1980. Libya intervened in support of the GUNT's President Goukouni Oueddei, against the former GUNT Defence Minister Hissène Habré.

Abba Siddick was a Chadian politician and revolutionary. He entered active politics in the Chadian Progressive Party (PPT), a nationalist and radical African political party founded in 1947 and led by Gabriel Lisette. By 1958, he had left the PPT to form with others the Chadian National Union (UNT), a Muslim progressive party, but he turned quite early to the PPT and, after the independence of Chad, was minister of Education of the President François Tombalbaye. However the President's discrimination against Muslims in Chad brought him to become a member of the rebel insurgent group FROLINAT, formed in 1966 to oppose the rule of Tombalbaye. After the death of the organization's first secretary-general in 1968, a vicious battle for leadership ensued, which terminated with the victory of Siddick in 1969, even though he was perceived as an Anti-Arab and suspected of being a moderate leftist and not having any revolutionary apprenticeship. He made Tripoli the headquarters of the front; and Libya took the place of Sudan as the key supplier of the FROLINAT. While he was internationally recognized as the head of the FROLINAT, he was losing control of the units on the ground. In 1971 he tried to reassert his authority by proposing to unify the insurgent forces active in Chad, but Goukouni Oueddei, head of the Second Liberation Army of the FROLINAT, broke with Siddick, who managed to at least keep a loose control over the First Liberation Army.

The Kano Accord was preceded by the collapse of central authority in Chad in 1979, when the Prime Minister, Hissène Habré, had unleashed his militias on February 12 against the capital N'Djamena and the sitting president, Félix Malloum. To tackle the President's forces, Habré had allied himself with the rival warlord Goukouni Oueddei, who entered N'Djamena on February 22 at the head of his People's Armed Forces (FAP).

Acyl Ahmat Akhabach (1944–1982) was a Chadian Arab rebel leader during the First Chadian Civil War. He was the head of the Democratic Revolutionary Council until his death in 1982, and served as the foreign minister of Chad under Goukouni Oueddei's government.

The Volcan Army was a Chadian insurgent rebel group that was active during the First Chadian Civil War. The movement was founded in 1970 by Chadian Arab insurgent leader Mohamed Baghlani, who had been expelled in June from the FROLINAT by the organization's secretary-general Abba Siddick. The new group was islamist and mainly composed of Arabs who shunned Siddick's leadership of the FROLINAT; it was based in Libya. For several years, until about 1975, the Volcan Army had little force on the ground, but after that it slowly expanded. Among the new members in 1976, Ahmat Acyl who attacked Baghlani's authority with the support of Libya in January 1977. When Baghlani died in a car accident in Benghazi on March 27, Acyl became the new leader of the militia with the full support of the Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi, and Acyl became his most loyal man in Chad.

Operation Épervier was the French military presence in Chad from 1986 until 2014.

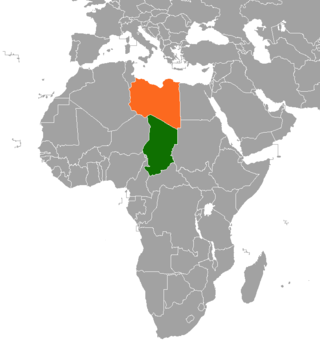

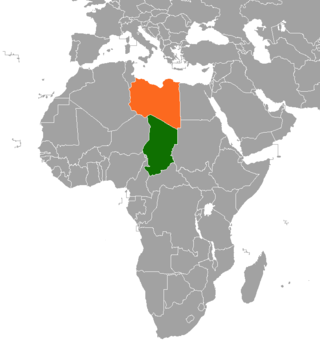

The Chadian–Libyan War was a series of military campaigns in Chad between 1978 and 1987, fought between Libyan and allied Chadian forces against Chadian groups supported by France, with the occasional involvement of other foreign countries and factions.

The Toyota War, also known as the Great Toyota War, which took place in 1987 in Northern Chad and on the Chad–Libya border, was the last phase of the Chadian–Libyan War. It takes its name from the Toyota pickup trucks, primarily the Toyota Hilux and the Toyota Land Cruiser, used to provide mobility for the Chadian troops as they fought against the Libyans, and as technicals. The 1987 war resulted in a heavy defeat for Libya, which, according to American sources, lost one tenth of its army, with 7,500 men killed and US$1.5 billion worth of military equipment destroyed or captured. Chadian forces suffered 1,000 deaths.

Operation Manta was a French military intervention in Chad between 1983 and 1984, during the Chadian–Libyan conflict. The operation was prompted by the invasion of Chad by a joint force of Libyan units and Chadian Transitional Government of National Unity (GUNT) rebels in June 1983. While France was at first reluctant to participate, the Libyan air-bombing of the strategic oasis of Faya-Largeau starting on July 31 led to the assembling in Chad of 3,500 French troops, the biggest French intervention since the end of the colonial era.

The Battle of Maaten al-Sarra was fought between Chad and Libya on September 5, 1987, during the Toyota War. The battle took the form of a surprise Chadian raid against the Libyan Maaten al-Sarra Air Base, meant to remove the threat of Libyan airpower, that had already thwarted the Chadian attack on the Aouzou Strip in August. The first clash ever held in Libyan territory since the beginning of the Chadian–Libyan conflict, the attack was fully successful, causing a high number of Libyan casualties and low Chadian casualties, also contributing to the definitive ceasefire signed on September 11 among the warring countries.

Chad–Libya relations have arisen out of centuries from ethnic, religious, and commercial ties.

The National Union for Independence and Revolution was the ruling party in Chad between 1984 and 1990. It was founded in June 1984 by President Hissène Habré as a successor to his Armed Forces of the North, the insurgent group through which Habré had conquered power in 1982. The party was banned after the 1990 coup d'état led by Idriss Déby.

The Chadian Civil War of 1965–1979 was waged by several rebel factions against two Chadian governments. The initial rebellion erupted in opposition to Chadian President François Tombalbaye, whose regime was marked by authoritarianism, extreme corruption, and favoritism. In 1975 Tombalbaye was murdered by his own army, and a military government headed by Félix Malloum emerged and continued the war against the insurgents. Following foreign interventions by Libya and France, the fracturing of the rebels into rival factions, and an escalation of the fighting, Malloum stepped down in March 1979. This paved the way for a new national government, known as "Transitional Government of National Unity" (GUNT).

The Claustre Affair was a hostage crisis during the First Chadian Civil War. Chadian rebels, calling themselves the Command Council of the Armed Forces of the North (CCFAN), led by Hissène Habré kidnapped Françoise Claustre, a French archaeologist, Marc Combe, a worker in a French development organization in Chad, and Christoph Staewen, a German doctor. Although Combe escaped and Staewen was ransomed back by the West German government, the rebels demanded a ransom of 10 million francs for Mrs. Claustre and her husband Pierre, who was later also captured by the rebels. The case garnered international attention, with the French sending a negotiator who was later executed. Finally the French appealed to Muammar Gaddafi to free the hostages, which he then did. The affair showcased Libya's growing influence in Central Africa.