Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker. He is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His paintings, drawings, and engravings reflected contemporary historical upheavals and influenced important 19th- and 20th-century painters. Goya is often referred to as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns.

The Naked Maja or The Nude Maja is an oil-on-canvas painting made around 1797–1800 by the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya, and is now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid. It portrays a nude woman reclining on a bed of pillows, and was probably commissioned by Manuel de Godoy, to hang in his private collection in a separate cabinet reserved for nude paintings. Goya created a pendant of the same woman identically posed, but clothed, known today as La maja vestida, also in the Prado, and usually hung next to La maja desnuda. The subject is identified as a maja or fashionable lower-class Madrid woman, based on her costume in La maja vestida.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker, and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media, he is generally considered one of the greatest visual artists in the history of art. It is estimated Rembrandt produced a total of about three hundred paintings, three hundred etchings, and two thousand drawings.

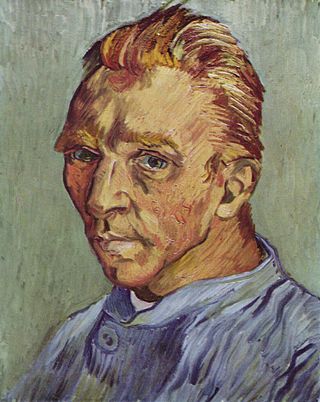

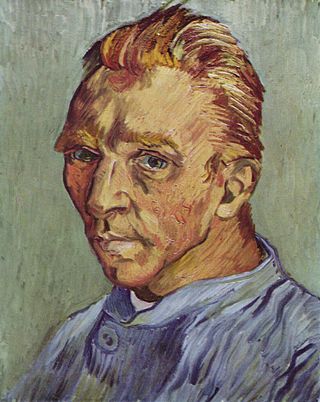

A self-portrait is a portrait of an artist made by themselves. Although self-portraits have been made since the earliest times, it is not until the Early Renaissance in the mid-15th century that artists can be frequently identified depicting themselves as either the main subject, or as important characters in their work. With better and cheaper mirrors, and the advent of the panel portrait, many painters, sculptors and printmakers tried some form of self-portraiture. Portrait of a Man in a Turban by Jan van Eyck of 1433 may well be the earliest known panel self-portrait. He painted a separate portrait of his wife, and he belonged to the social group that had begun to commission portraits, already more common among wealthy Netherlanders than south of the Alps. The genre is venerable, but not until the Renaissance, with increased wealth and interest in the individual as a subject, did it become truly popular.

Genre painting, a form of genre art, depicts aspects of everyday life by portraying ordinary people engaged in common activities. One common definition of a genre scene is that it shows figures to whom no identity can be attached either individually or collectively, thus distinguishing it from history paintings and portraits. A work would often be considered as a genre work even if it could be shown that the artist had used a known person—a member of his family, say—as a model. In this case it would depend on whether the work was likely to have been intended by the artist to be perceived as a portrait—sometimes a subjective question. The depictions can be realistic, imagined, or romanticized by the artist. Because of their familiar and frequently sentimental subject matter, genre paintings have often proven popular with the bourgeoisie, or middle class.

Saturn Devouring His Son is a painting by Spanish artist Francisco Goya. It is traditionally interpreted as a depiction of the Greek myth of the Titan Cronus eating one of his offspring. Fearing a prophecy foretold by Gaea that predicted he would be overthrown by one of his children, Saturn ate each one upon their birth. The work is one of the 14 so-called Black Paintings that Goya painted directly on the walls of his house sometime between 1820 and 1823. It was transferred to canvas after Goya's death and is now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

Charles IV of Spain and His Family is an oil-on-canvas group portrait painting by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya. He began work on the painting in 1800, shortly after he became First Chamber Painter to the royal family, and completed it in the summer of 1801.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters or The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters is an aquatint by the Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya. Created between 1797 and 1799 for the Diario de Madrid, it is the 43rd of the 80 aquatints making up the satirical Los caprichos.

The Dog is the name usually given to a painting by Spanish artist Francisco de Goya, now in the Museo del Prado, Madrid. It shows the head of a dog gazing upwards. The dog itself is almost lost in the vastness of the rest of the image, which is empty except for a dark sloping area near the bottom of the picture: an unidentifiable mass which conceals the animal's body. The placard for The Dog painting in The Prado indicates the dog is in distress, quite literally, drowning.

Yard with Lunatics is a small oil-on-tinplate painting completed by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya between 1793 and 1794. Goya said that the painting was informed by scenes of institutions he had witnessed as a youth in Zaragoza. Yard with Lunatics was painted around the time when Goya’s deafness and fear of mental illness were developing and he was increasingly complaining of his health. A contemporary diagnosis read, "the noises in his head and deafness aren’t improving, yet his vision is much better and he is back in control of his balance."

Witches' Sabbath or The Great He-Goat are names given to an oil mural by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya, completed sometime between 1821 and 1823. It explores themes of violence, intimidation, aging and death. Satan hulks, in the form of a goat, in moonlit silhouette over a coven of terrified witches. Goya was then around 75 years old, living alone and suffering from acute mental and physical distress.

La Leocadia or The Seductress are names given to a mural by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya, completed sometime between 1819–1823, as one of his series of 14 Black Paintings. It shows a woman commonly identified as Goya's maid, companion and lover, Leocadia Weiss. She is dressed in a dark, almost funeral maja dress, and leans against what is either a mantelpiece or burial mound, as she looks outward at the viewer with a sorrowful expression. Leocadia is one of the final of the Black Paintings, which he painted in his seventies at a time when he was consumed by political, physical and psychological turmoil, after he fled to the country from his position as court painter in Madrid.

A Pilgrimage to San Isidro is one of the Black Paintings painted by Francisco de Goya between 1819–23 on the interior walls of the house known as Quinta del Sordo that he purchased in 1819. It probably occupied a wall on the first floor of the house, opposite The Great He-Goat.

Two Old Men, also known as Two Monks or An Old Man and a Monk, are names given to one of the 14 Black Paintings painted by Francisco Goya between 1819-23. At the time Goya was in his mid-seventies and was undergoing a great amount of physical and mental stress after two bouts of an unidentified illness. The works were rendered directly onto the interior walls of the house known as Quinta del Sordo, which Goya purchased in 1819.

The Madhouse or Asylum is an oil on panel painting by Francisco Goya. He produced it between 1812 and 1819 based on a scene he had witnessed at the then-renowned Zaragoza mental asylum. It depicts a mental asylum and the inhabitants in various states of madness. The creation came after a tumultuous period of Goya's life in which he suffered from serious illness and experienced hardships within his family.

The Black Paintings is the name given to a group of 14 paintings by Francisco Goya from the later years of his life, likely between 1819 and 1823. They portray intense, haunting themes, reflective of both his fear of insanity and his bleak outlook on humanity. In 1819, at the age of 72, Goya moved into a two-story house outside Madrid that was called Quinta del Sordo. Although the house had been named after the previous owner, who was deaf, Goya too was nearly deaf at the time as a result of an unknown illness he had suffered when he was 46. The paintings originally were painted as murals on the walls of the house, later being "hacked off" the walls and attached to canvas by owner Baron Frédéric Émile d'Erlanger. They are now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

Zvi Malnovitzer is an expressionist painter born to a Haredi, or ultra-Orthodox, religious family in Bnei Brak, Israel. His upbringing in a society isolated from the modern world, where he was dedicated to intensive and uninterrupted Talmudic study from a young age, makes his decision to become an artist unusual, bold, and one of accomplishment. During his training in Reichenau, Austria, where he studied under the auspices of artist Wolfgang Manner and under the direction of Ernst Fuchs, Malnvotizer developed a unique style portraying themes that straddle the religious and secular worlds.

Judith Slaying Holofernes c. 1620, now at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, is the renowned painting by Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi depicting the assassination of Holofernes from the apocryphal Book of Judith. When compared to her earlier interpretation from Naples c. 1612, there are subtle but marked improvements to the composition and detailed elements of the work. These differences display the skill of a cultivated Baroque painter, with the adept use of chiaroscuro and realism to express the violent tension between Judith, Abra, and the dying Holofernes.

Summer or The Threshing Floor is the largest cartoon painted by Francisco de Goya as a tapestry design for Spain's Royal Tapestry Factory. Painted from 1786 to 1787, it was part of his fifth series, dedicated to traditional themes and intended for the heir to the Spanish throne and his wife. The tapestries were to hang in the couple's dining room at the Pardo Palace.

Spanish Baroque painting refers to the style of painting which developed in Spain throughout the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century. The style appeared in early 17th century paintings, and arose in response to Mannerist distortions and idealisation of beauty in excess, appearing in early 17th century paintings. Its main objective was, above all, to allow the viewer to easily understand the scenes depicted in the works through the use of realism, while also meeting the Catholic Church's demands for 'decorum' during the Counter-Reformation.